Pretty Pictures and Million-Dollar Fakes

Memories and Images:The World of Donald Vogel by Donald Stanley Vogel

296 pages, $39.95.

Our pride is more offended by attacks on our tastes than on our opinions.

— La Rochefoucauld, Maxims

The pride of many Dallasites is likely to feel chafed-if not downright flayed-by Donald Vogel’s new memoir, an engaging, often brazen account of art adventures in Big D during the last 60 years. A lifelong painter, Vogel was also Dallas’s pioneering fine art dealer, opening in 1954 Valley House Gallery, which remains in business today. He saw the city develop from an artistic backwater into a far more culturally diverse and sophisticated place, now with several museums and some 40 galleries. Having not just witnessed but in many instances carved these changes out by hand, Vogel unflinchingly records in Memories and Images a host of flops, follies, and artistic triumphs along the way.

Soon after his arrival in the early 1940s, fresh from the Chicago Art Institute, Vogel met with creeping dismay: “I began to believe Dallas had a department store culture,” he writes. “Neiman Marcus, one of the greatest stores in the country, seemed to be dictating taste. The Neiman’s label became a status symbol, and citizens wore it as their badge of success. Too many people came to believe they could buy taste and need not try to develop it.” These are fighting words, and Vogel through the years never shied from confrontation; in fact, his many scrapes with the smug first families and bullying oilmen of Dallas bring suspense and comedy to what might otherwise have been rather mundane recollections of a regional art scene.

Vogel portrays himself as the pugnacious maverick, a tough little David who keeps flinging his artistic standards into the face of Dallas’s lumbering giants. Stories from his youth show that he developed this attitude the hard way. Tossed out first by his own parents, then, because he could no longer afford tuition, by the art school dean, Vogel came to town owning nothing but a determination to keep painting and confidence in his own taste. He became the custodian and set designer for the Dallas Little Theater and fell in with an energetic group of Fort Worth artists, whose camaraderie sustained him.

Wriggling his way into the nascent visual art scene of Dallas, then little more than a few frame shops, painting clubs for wealthy hobbyists and one slumbering museum, Vogel began mounting shows of contemporary art wherever there was bare wall space. In five years he had developed a reputation as “the most modern painter in Dallas.” Thus he was described by Betty McLean. A woman of means and influence, she befriended Vogel and in 1950 dropped her plans to open a beauty salon to become his partner in Dallas’s first contemporary art business, Betty McLean Gallery. With characteristic boldness, Vogel organized the first show in conjunction with the venerable Knoedler Gallery of New York, bringing to Dallas a group of works by Chagall, Winslow Homer, Cassatt, Renoir, Matisse, and a half dozen more modern masters; $6,000 would have picked up a large Monet. “It all seems ridiculous now,” Vogel writes. “We failed to sell any of them; people complained that the prices were unreasonable.”

Into a milieu then blind to much beyond Remington’s bronze bronc riders, Vogel and his first wife Peggy pressed on. When Betty McLean left the gallery business, they created Valley House in a more bucolic setting north of the city, interchanging shows of their favorite regional artists with works by nationally and internationally known painters and sculptors. The Vogels managed a number of world-class shows through their contacts with some of the top dealers in New York and abroad. Among them was Robert de Bolli of Paris, who represented the estate of famed Ambrose Vollard, with its trove of Impressionist and post-Impressionist works. The Vogels also brought Texas naive painter Clara MacDonald Williamson to public attention, introducing her work to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and arranging a retrospective exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum in 1966.

Venard was represented by Valley House from 1953 to 1962. But these were mere successes. For Vogel, it was as much or more the repeated affronts and failures that honed his aesthetic, drove him back to the studio to paint, and stiffened his ambition to make an impact on the city.

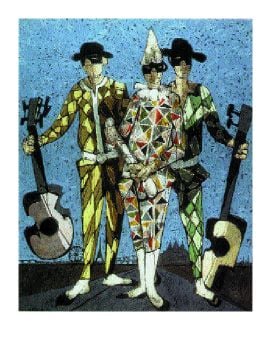

He relates how one prospective buyer turned down a Picasso harlequin painting that clashed with her sofa and how the Dallas Museum missed its chance to acquire one of Monet’s great water lilies (Nymphéas). “I tried in every way, directly and through friends and board members, to move (the museum director) to buy it for the museum. I never succeeded. Maybe if it had been a painting of a cactus or a jackrabbit he’d have been more inclined.” Vogel writes that crating the painting “felt like putting a dear friend in a coffin. Dallas had just lost a masterpiece, as we would lose many more.”

The most extended of these stories, and for Vogel the most heartbreaking, was Valley House’s exhibition of Rouault’s Passion, 54 religious paintings Vogel had dreamed for a decade that Dallas might acquire. The Vogels poured $30,000 into the 1962 exhibition, its promotion and documentation. The paintings earned international acclaim from critics but Dallas’s elite could not be convinced to purchase them. The works now belong to a museum in Japan.

One can’t help but think that some of these losses were in part the result of Vogel’s own personality: intractable, non-elitist, and more than a little haughty. He admits to being no salesman. “Generally, I did not seek out clients,” he writes. With faith in the art he admired, Vogel’s technique was simple: to place works on view in an attractive environment, then, “with full respect for the viewer, I restrained myself from telling him what he saw. It’s the individual’s response that’s important, not mine.”

Savvy as he was about the value of making powerful friends, he made powerful enemies too. Most memorably it was Vogel who first acknowledged that tycoon Algur Meadows’s million-dollar collection of Impressionist paintings consisted mainly of fakes, a call later confirmed by a team of international experts. With money to burn, Meadows just acquired a new collection, authentic this time; he never bought a painting through Vogel.

Vogel’s purely aesthetic approach was eventually challenged from within the art world. Regional artists, while never prosperous, had enjoyed increased opportunities through the 1940s, when Vogel headed to Dallas, but “these activities would decline in the coming years,” he writes, “giving way to the national standard of ‘leading edge’ art. Local art slowly disappeared until it was all but non-existent as far as the local museums were concerned. It would be up to the galleries to prove it still existed. A new and different awareness was developing instead, one that required more and more words to explain the pictures that were hung. It seemed the less content a painting had, the more words flowed to explain it.”

In 1961, Vogel was stunned to encounter young New York artists who scoffed at his respect for “charm, delight, pleasure, atmosphere” as artistic virtues. “They pounced upon me and informed me that painting could no longer be described in such terms.” In both his own work and that of the artists he represented, Vogel always sought “the creation of an aesthetic experience rather than…a cultural statement.” Much of the art he made and championed would be disparaged by art sophisticates today as “pretty pictures.”

Art history, like all history, is written by the winners, which explains why there are so few accounts of regional art and its society. Like pop music and publishing, art has become a winner-take-all enterprise, except that in the art realm even winners sometimes go hungry, grateful just to devour their favorable press clippings. Vogel’s book is overstuffed with “I told you so” stories and overstates the purity of his aesthetic standards (after all, he did concede to adding two poodles to Mrs. H.L. Hunt’s family portrait). Still his memoir supplies a rare and valuable chronicle of a half century in Texas art, naming names, quoting prices, and-eat your heart out, Dallas-telling how too many big ones got away.

Julie Ardery is the author of The Temptation: Edgar Tolson and the Genesis of 20th Century Folk Art (University of North Carolina Press).