Back of the Book

The Hearst of Times

I miss Yellow Journalism.

I mean obviously I wasn’t there, 110 years ago, when William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were duking it out for supremacy in a New York City newspaper war. But I went to work for the genre’s alt-weekly inheritors—which shared the Yellow Period’s taste for self-congratulatory advocacy, anti-authority muckraking, overheated prose and stunt journalism—as fast as I could. I’ve been doing something or other in the alt-weekly universe, of which the Observer is a curious planet, for 18 years—as old as I was when I published my first “satirical” college magazine. I missed the birth of newspapers. Now it looks like I get to watch them die.

I just got off the phone with a friend in Ann Arbor, Michigan. By the by she mentioned that the 174-year-old Ann Arbor News, the college town’s only daily, is closing shop this summer, to be replaced by a Web site and a twice-weekly print edition. The Cox Media-owned daily in Austin, where I live, is for sale, and can’t seem to get a bite. The 146-year-old Hearst-owned Seattle Post-Intelligencer slashed its staff from 165 to 20 and went Web-only last month. The 150-year-old Rocky Mountain News, owned by Scripps, just did the same. Hearst’s San Francisco Chronicle, an indirect descendant of the Hearst family’s foundational San Francisco Examiner, is for sale and could close.

Closer to home, Hearst’s flagship Houston Chronicle laid off 80 people six months ago. As this issue was being edited, management was in the middle of another two-day bloodletting that left the halls littered with the tenures of close to 90 journalists, from longtime books editor Fritz Lanham to Austin bureau veteran Clay Robison to popular features writer Clifford Pugh.

The Hearst-owned San Antonio Express-News cut 75 newsroom positions in March. Hearst also owns the Beaumont Enterprise, the Laredo Times, the Midland Reporter-Telegram and the Plainview Daily Herald. I don’t know how they’re doing.

You don’t even want to know what happened to Pulitzer. The venerable chain, including the flagship St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was bought four years ago by the Midwestern middle-market lightweight Lee Enterprises. Pulitzer got out of the business just in time; the combined companies are now valued at about a third of what Pulitzer alone was worth when Lee bought it.

At least Pulitzer has that prize to burnish its reputation.

Hearst has the shaky remains of empire (grandson George R. Hearst Jr. chairs the board of directors of Hearst Corp., a pretty well diversified multimedia company that can’t seem to figure out what to do with its ill-performing papers) and a new biography as laurels.

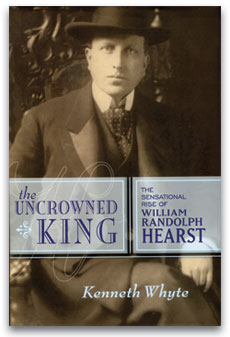

The book, by Canadian editor-publisher Kenneth Whyte, is called The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst, and it’s every bit as swashbuckling as its title.

The “sensational rise” of William Randolph Hearst took place during about five years in the late 1800s. Hearst’s rise was followed by entrenched power, humiliating political defeats, corporate desert-wandering and entrenched power again, none of which Whyte covers.

So it’s properly neither a personal nor corporate biography. There have been dozens of attempts at those over the years. Whyte is mostly out to argue against the popular conception of Hearst as a shallow, philandering ne’er-do-well who dragged the once-respectable journalist’s trade into a gutter of sensationalism, cronyism, self-dealing and outright fiction. The gist of Whyte’s argument is that while Hearst’s detractors have a point, Hearst wasn’t actually quite as bad as all that, and had a hell of a lot of innate newspapering talent besides.

As revisionism goes, this is relatively small beans, but it does remind one that print journalism has had many Yellow Periods (read the first third of The First American, H.W. Brands’ biography of Ben Franklin, and see what you think of a founding father’s idea of newspaperly propriety), and as many golden ages (from the Alsop brothers to Lincoln Steffens to H.L. Mencken to Murray Kempton). It will certainly have more in the future.

But it doesn’t look like those golden ages will have much to do with newsprint. Hearst has to know it. The company owns TV stations and Internet companies and ESPN, and its latest brainstorm is an e-reader apparently designed to do for newspapers and magazines (Hearst owns Esquire and Marie Claire, among other glossy titles) what Amazon’s Kindle is trying to do for books, i.e. dominate a market of e-readers that has yet to stand and be counted. The hope is to “monetize” the “content.”

May we all.

I would never condone just making stuff up, Yellow Journalism-style, because journalists really shouldn’t do that. I only did it once, a long time ago, but it was funny, so it was OK.

I was at an alt-weekly, so I assumed that sort of thing was expected. I was a music critic then, and every music critic knew that the heroic Lester Bangs had been known to review records without ever removing the shrink-wrap. Every music critic knew why and how—and which of us wasn’t going to try that? Mine was a review of a record by a Houston band called Shag Assmeal and the Feuding Choads. No such record. No such band. You can bet they rocked. And though I never checked, I feel sure circulation went through the roof that week.

Pure invention aside, the rest of Yellow Journalism’s rap sheet seems a bit prudish in retrospect. Papers sensationalized reporting to attract readers? Que scandal? They lobbied for their publisher’s politics? Shocked and appalled. They started an unnecessary war? OK, not so good, but at least they could. If a newspaper could start a war, then a newspaper could theoretically stop one.

Journalism, when it wasn’t awful, was daring back then. Reporters jumped from ferries to gauge emergency response times. They raced cross-country on bicycles chasing trend stories. Publishers spent top dollar to lure top talent—writers, illustrators, editors—away from the competition. They invested lavishly in state-of-the-art printing presses and special trains to get their papers to market. One of Hearst’s first moves as a fledgling publisher was to commission the building of the world’s fastest steamship to announce his arrival on the scene. All the big publisher-editors had elaborate yachts.

Today, newspapers can’t seem to keep their heads above water. It’s not just the dailies. The alt-weeklies are staggering, too, though they don’t have to worry about stagnant subscription rates since they’re already accustomed to giving it away. One of the alt-weekly world’s bigger players, Tampa, Florida-based Creative Loafing, is in a bankruptcy battle with the financiers who funded the chain’s disastrous expansion of the last few years. The advertising just isn’t there to support it. According to job posts at the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies Web site, just about nobody’s hiring.

It’s probably going to be OK. It’s easy to forget while we’re wringing our hands on the deathwatch, but a lot of newspapers, especially daily newspapers, have sucked for a long time. They’d transformed themselves into bottom-line grinds well before the current economic crunch arrived, and if they now find themselves at the mercy of a merciless logic, well, they kind of asked for it. Long, lazy years of 30-percent profit margins and monopoly consolidation will do that. Too many newspapers put all their eggs in one basket and now the economy is sitting on it.

We’ll miss them, sure. Many were important to their communities in ways that Facebook and Craigslist are unlikely to replicate, and they carried some important and entertaining stories in their day. And print, despite its inefficiencies, has compensating tactile pleasures that can’t be electronically reproduced. Readers with corresponding niche tastes will likely continue to find themselves catered to with subscription-bonus dead-tree editions. But the urge will fade, and the habit—and it’s just a habit—will die.

Newspapers just aren’t the best way to do the things that used to make newspapers money anymore. As physical objects, as business models, and as delivery systems for journalism, they’re badly outmoded—sort of like GM cars. Would a world without The New York Times, say, be any worse than the world has been without Oldsmobile? Well, yes, probably, but we’ll probably learn to get along without USA Today and a whole raft of lesser lights.

Still, it’s worth remembering that even so venerable an institution as The New York Times was barely even a player—and certainly not a paper of record—in the late 1800s, when Willie Hearst packed up his greenhorn experience at the San Francisco Examiner, which his daddy’d given him, moved to New York, bought a paper called the Journal, and went head to head with Joseph Pulitzer and his reigning World for supremacy in American journalism. Times change. The Times will change, too.

Here’s another thing that’s changed: Hearst seemed to think—and Pulitzer wasn’t known to disagree—that a newspaper could be a country’s seat of power, more so even than government. It was a democratic notion, a weight of responsibility spread across the back of every two-bit Joe with a few cents to spend on a paper. It was a dictatorial notion, too. When Hearst got pissed that RKO was putting out Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane—which both defamed and enshrined Hearst and his family—Hearst’s response was to refuse advertising for the film in his papers, and to threaten an exposé campaign on Hollywood’s elite if the film was released.

Try to imagine a publisher today threatening Hollywood, or anyone, with refusal of advertising. That wouldn’t pass an editor’s smell test even in fiction.