Back of the Book

The Cartoon Versions

“Oh Daniel, Daniel, Daniel, Daniel … Please … Do grow up. My new world demands less obvious heroism, making your schoolboy heroics redundant.” —Big-brained villain Ozymandias to out-of-retirement Night Owl, aka Dan Dreiberg, in Watchmen.

Were you a comics geek growing up? If you answered yes with a cringe, expecting some sort of highbrow beatdown, get over it. We get it. Comic book geeks are the heroes now.

It’s true that when critics describe a character as a “cartoon” or “comic book” version, they’re not generally offering praise. They’re calling out two-dimensional, plastic, second-rate fakes. “Comic book” doesn’t live far from “caricature.” No depth there, is the slur. Just exaggerated gestures.

But that cliché is long-crumbled. Comic book narratives—recast as graphic novels and describing an ascendant arc of public reputation over the past 40 years—have been elevated beyond mere respectability. If ever there was a meaningful distinction between comics and, say, art: Zap! Pow! GONE!

Comics started to stop being kid stuff in the midcentury hands of artist-writer Jack Kirby and writer Stan Lee (Captain America, Incredible Hulk, Fantastic Four, X-Men, et al.). They became adult in the 1960s under the leering watch of R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson. Comics began colonizing the novel in the mid-1980s with Art Spiegelman’s trailblazing Maus, Alan Moore’s (and Dave Gibbons’) de- and re-mythologizing Watchmen, and Frank Miller’s revisionist (for those of us who grew up on Adam West) Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

Along the way, comic book superheroism stopped trying to appeal to the psychology of children and started exploring the psychology of its characters and authors. It probably had to happen. The audience was growing up. And the masks more or less demanded lifting.

Down at the mall, we’ve been watching the ongoing metroplexual revisitation of the two-dimensional cartoon cliché for what’s starting to seem like forever. The Incredible Hulks. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Iron Man. Hellboys I (still my favorite) and II. The Spider-Man and Batman franchises. X-Men. I’m probably forgetting a bunch. A lot have been forgettable.

What superhero movies now have in common is a fetish for unmasking fictional do-gooders as flawed (or better, psychotic) flesh-and-(lots-of)-blood human beings. Superheroes are antiheroes now, and the superfriends don’t stay much in touch. Fair enough.

It’s been a long time since super- hero movies were for kids. The Dark Knight collected eight Oscar nominations last year, banking record-setting box-office receipts for Heath Ledger’s unhinged Joker.

And now comes Watchmen, the fanboy motherlode, which opened around the state recently. The plot revolves around the assassination of a retired superhero and the reactions of his mostly out-to-pasture peers: the Comedian, Night Owl II, Rorschach, Silk Spectre II, Doctor Manhattan, and Ozymandias. About the only traces of kid in the movie are the dog-gnawed bones of a sexually tortured little girl and flashbacks to the traumatic childhood of the man who grows up to avenge her death by repeatedly burying a meat cleaver in her abuser’s skull.

Take the whole family.

“I like Picasso, I like Salvador Dali, you know, I like all the great ones. When I was a kid, they used to let me check out stacks of art books all the time, you know. I just pored over them all the time.” —Daniel Johnston

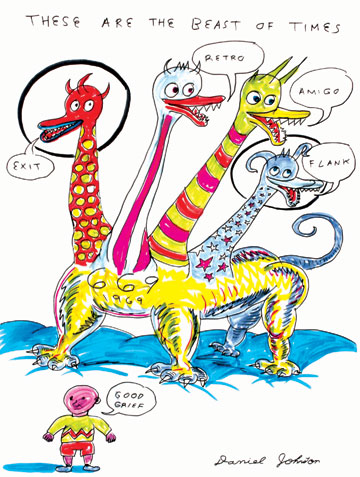

Rizzoli’s publication this month of Daniel Johnston, a large-format art book of the Waller-based artist’s comics-based drawings, won’t garner a fraction of the attention that Watchmen will, but it’d be nice to think that it should, if only for its illustration of superhero counterpoint and refreshing self-deflation of hype:

“THIS IS LIKE THE BIG TIME” says the thought-bubble emerging from Joe the Boxer’s scooped-out head on the book’s cover.

“WHO CARES” says three-eyed Vile Corrupt.

People who like cartoon superheroes might.

Johnston, as you ought to know, is a bipolar singer-songwriter with a preternatural sense for pop songcraft and a savant’s skill with emotionally resonant one-liners. He’s more recently found a second level of fame as a visual artist. His work was featured at the 2006 Whitney Biennial. His notebook scribbles sell through his Web site for $175 and up.

Daniel Johnston collects early drawings, notebook sketches and color-soaked recent work with a running interview and short essays by admirers including musician Jad Fair and comic artist Harvey Pekar.

Joe the Boxer and Vile Corrupt are just two of Johnston’s recurring characters. Jeremiah the Innocent Frog and Casper the Friendly Ghost share the page with devils and ducks and headless female torsos and male heads with the caps of their skulls lopped off. Johnston is fond of headless stuff and, alternately, stuff with lots of heads.

His characters, mostly in Magic Marker, crowd the pages until they’re full, figures overlapping figures that may or may not have anything to do with each other.

In one rare watercolor self-portrait he strums a guitar and sings “I LOST THE TALET CONTEST. I’M DIS-APOINTED” [sic throughout] to a line of seated skulls.

In another he pictures himself as a smiling Frankenstein asking the nice people “WOULD YOU LIKE A TAPE?”

His characters speak in mock-ironic epigrams and weird aphorisms:

“TIMES ARE HARD BUT GOSPEL SINGERS ARE IN NO WAY TIRED.”

“LIVE LONG AND PROSPRATE.”

“KILL EM ALL!” deadpans a mace-wielding duck walking across a field of skulls.

“HELL AIN’T ALL BAD IT’S WORSE!”

And my new favorite exhortation: “DEATH TO BAD.”

Johnston’s bad guys are simple: Satan and Nazis, usually.

Some of Johnston’s cartoon heroes are actual cartoon heroes: Captain America, the Incredible Hulk (“I’M A HULK OF PERSONALITY”), Batman. They’re just not always in starring roles. They share the book with cigarette-smoking old ladies and pretty girls waiting for who knows what and all manner of doodled hodgepodge. There’s no comic strip here, per se, just disassociated comic elements from Johnston’s enigmatic and tragicomic cosmology.

That cosmology found a coherent and moving expression last year about this time when Houston theater troop Infernal Bridegroom Productions mounted Speeding Motorcycle, an original rock opera built around and of Johnston’s songs. The play, produced first in Houston and then in Austin, read like a live-action comic book brought to stage, where Johnston’s alter egos battled demons inner and elsewise, and emerged, for the time being anyhow, victorious.

Johnston is no naïf. There’s a fine line and an easily discernable difference between childish and childlike, and Johnston knows where it is, and what side he stands on.

Good versus evil is an easy tell in Johnston’s world: Good equals innocence, and evil has many eyes.

” … it seemed to me that if you see more than just innocence in life, if you see more of the negativity, pornography or violence or other things, that it would affect you if you thought about it too much.” —Daniel Johnston

People used to dismiss comics as kid stuff because it was kid stuff. But it was too fecund a form to stay kid stuff forever, so it grew up. Now much of it seems hardly suitable for kids. I note this as a nonparent, which is to say as a person who doesn’t particularly give a damn about the children. Good luck to them.

Watchmen is neither childish nor child-like. The Comedian’s humor is cruelly existential, rape his idea of a punchline. The supposedly smartest human on Earth is an unapologetic mass murderer. The moral soul of the story, the face-shifting Rorschach, is the emotional equivalent of a scab.

Watchmen and Daniel Johnston share a preoccupation with the idea of evil run rampant, flooding the gutters with violence and filth, but they illustrate two entirely different strategic solutions to the end of innocence.

The Watchmen way is to wallow in compromise and regret, all the while riffing on and simultaneously undermining the foundational mythologies of superherodom: Life is a joke, now choke on it.

Johnston, the hero of his own universe, reacts with winks and nudges and invitations to get in on the gag. Good smiles when it has evil at bay.

The money image from Watchmen is a pile of corpses dripping their bleeding innards across a clockface struck midnight. Nobody said Alan Moore was subtle.

A typical Daniel Johnston takeaway line is “HOWDY PLEASE DIE ASS SATAN.”

Only one of those is really any fun.