A Bimusical Mind

Like many Mexican-Americans from South Texas, Manuel Peña’s family survived hard times working as migrant agricultural laborers. What makes Peña’s story singular is that after becoming the first member of his immediate family to continue school past eighth grade, he went on to earn a doctorate in anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin and join the humanities faculty at California State University at Fresno.

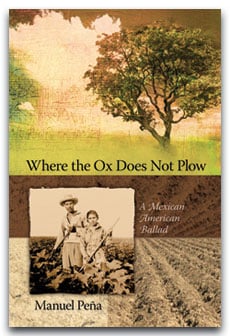

Peña, now retired, calls his new book, Where the Ox Does Not Plow, an autobiographical ethnography. It’s a deeply personal departure from his academic works on Mexican-American musical styles. Rather than a linear autobiographical narrative, the book presents 26 episodes along Peña’s journey from cotton picker to distinguished scholar, with an eye out all the while for the larger cultural significance of his biographical particularities.

His observational and descriptive powers are remarkable, and employed in the service of tales that range from wrenching to humorous. Peña’s writing here is lyrical, elegant and evocative, conveying history through storytelling, and making tangible the smell of the earth, the ache of overworked muscles, the fierceness of thunderstorms. The odd simile delights, as when he describes “slender palm trees that swayed like hula dancers.”

Peña was born in Weslaco, near McAllen, in 1942, and for most of his youth his family drifted, working as hired hands or sharecroppers. They eventually settled in California, where Peña has lived most of his adult life. Peña blames his family’s itinerancy on his father’s alcoholism and a severe 1947 ice storm that disrupted the economy of the Rio Grande Valley, and decades later his memories of racial prejudice and economic deprivation remain raw. As an admittedly sensitive child attracted to schoolwork and stability, the disruptions of the migrant life frustrated him deeply.

The power of weather in steering the Peñas’ course is a frequent theme. In one story, Peña recalls playing farmer in the dirt as a child, fetching water from a pump to pour on the miniature plots, willing the imaginary rain to save his family’s parched crops.

If the weather required adjustments, so did Anglo culture. In “The Taco and the Sandwich,” Peña remembers his mortification on the first day of school when his fellow Mexican students mocked him for bringing a taco for lunch. He tells his mother he wants to eat “comida Americana,” requiring his father to drive seven miles to buy bread and bologna. Thus did Peña develop an early “vague notion of the difference between things American and the exclusively Mexican world I had known until yesterday.” As a professor, Peña liked to tell his folklore students, “I may look Mexican to you, but, believe me, I’m as American as Taco Bell.”

In “Heavenly Saturday,” Peña describes arduous 10-hour days of picking cotton and stuffing it into the 50-pound bag he dragged—a smaller-than-standard bag made especially for him by his father, in consideration of his tender years. It was on Saturdays that the family relished the luxury of a cabin heater to warm bath water with which to remove the work week’s “five-day layer of grime.” On one occasion, after enjoying a Spanish charro (or Western) movie in a tent theater, he and his brother tried to buy hamburgers at a walk-up food stand, only to have the owner tell them, “We don’t serve Mexicans here.”

Noting that the local economy must surely have benefited from the migrants’ cash, Peña reflects, “For the remainder of our lives, our attitude toward male gringo strangers would be colored by that brief but tense encounter.”

Cultural misunderstandings cut both ways, and as a child Peña harassed yellowjackets with his nigasura, or slingshot, unaware of the term’s racist origins.

In “Over my Dead Body,” Peña tells of his fifth-grade teacher’s diatribe against integration after the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. He uses this anecdote as a springboard for discussing race relations and the variations on prejudice he observed on his family’s travels. Although some farmers employed both brown and black workers, Peña noticed that when the weekend came the kids socialized separately. “Mexicans absorbed Anglo prejudices,” Peña observes. “To put it bluntly, the Mexicans thought of the African Americans as slackers who generally possessed a low level of thrift, intelligence, and motivation.”

In contrast, or at least clarification, a later vignette called “California Dreamin'” describes competition in California orchards from fuereños, or illegal Mexican laborers, and his brother’s angry demand that they not work so fast. The foreman noted their failure to match the pace of the other workers and laid them off. Furious, his brother declared, “We’re not slaves of these cabrones,” and the young men left without collecting their pay for a day and a half of work.

As a teenager back in Weslaco, Peña formed the Matadors, a “bimusical” trio that performed Top 40 hits along with boleros and other Spanish songs. Angry that until the ninth grade he had never been able to begin school before December because of the obligations of harvest season, he told his father, “I am not going to pick cotton or anything else ever again.” A supportive gringo had helped the Matadors land a regular weekend gig at the most glamorous hotel in the area, even as Peña’s father had secured him work as an irrigator. For a time the young musician alternated between daytime toil in the fields and evening work across the tracks, “where the streets were paved.” Despite his determination to escape the fieldworker’s life, he writes, “My emancipation from the agricultural fields and the legacy of exploitation, shame, and deprivation … would come about in piecemeal fashion.”

Peña finally made the transition for good after beginning college, only to find himself in the uncomfortable company of incendiary young Chicano revolutionaries who questioned his commitment to the nascent Brown Power movement.

“The good life: after all those years of struggle and frustration, it seemed to be within your grasp, and you didn’t want to sacrifice it for some crazy revolutionary slogan,” Peña rationalizes. Thinking that his own connection with Mexican culture was surely deeper than his tormenters’, he defended himself. “Look, I may not go around shouting, ‘I am Chicano!,’ but in my own way I’ve tried to help my people. I know where my roots are.”

Still, the encounter, combined with the ferment of the times, led to another transformation: “My ethnic consciousness had begun to blossom. … I took on with zest the task of reinventing my identity. Those were heady days when I reached deep into my roots to redefine myself.”

One manifestation of Peña’s new consciousness was his stylistic migration away from the sophisticated, Big Band-emulating orquesta style music he had been playing, and into the embrace of earthy, working-class conjunto music.

Peña takes his title from a saying often quoted by his father: “Where can the ox go that he won’t have to plow?” The question took on further resonance when Peña read With His Pistol in His Hand, the seminal work by his academic mentor Américo Paredes, in which he learned of the flagrant persecution of Mexican-Americans in Texas history and realized that “The yoke of the ox that I had worn since childhood was crumbling loose.”

But exploitive labor was hardly Peña’s only burden, and some of the most poignant writing here describes his intense but conflicted attraction to generally unattainable Anglo women. Though he acknowledges that “Adventuresome adolescents were laying the groundwork for the more enlightened race relations of the next generation” with the occasional interracial teen romance, he also recognizes in retrospect that his Anglo elementary school sweetheart was probably willing to associate with Mexican Americans only because other Anglos shunned her after her father abandoned the family, forcing her mother to go to work.

In a briefly described affair with a half-Mexican teacher who intrigues him with her fluent Spanish and love of dancing, he seems most entranced with her “sage blue” eyes.

The book’s concluding tale, “Love in the Time of Hurricanes,” interweaves Peña’s praise of his wife—who was raised in the same agricultural and musical milieu that he was—with descriptions of Peña’s romantic obsession with a cosmopolitan Anglo colleague. The woman tells him it’s his marriage that causes her restraint, but Peña imagines his ethnicity as the primary obstacle. Their relationship never develops beyond lunch dates.

The order of these tales is roughly chronological within Peña’s broad thematic frames, but the continuity is occasionally disrupted. His widowed father’s postmarital misadventures, for instance, come before Peña’s tribute to his late mother. And the book’s episodic nature leaves out some presumably important aspects of the author’s story. Peña’s scholarly writing interested me in the question of how his background affected his intellectual development in graduate school, but Peña pays virtually no attention to the topic, aside from passing mention that he applied Marxist theories to his study of Tex-Mex culture. He dwells on the curse of panic disorder in his family line, and the ways in which it proved socially debilitating for his mother, but makes only cursory reference to the mental-health challenges he himself faced as a professional academic.

This book’s anecdotes of Peña’s early life provide tantalizing glimpses into a bimusical and bicultural mind but left me wanting to know more about how he got from there to here. Peña has said he’s working on another volume; perhaps it will dig more deeply into that extraordinary intellectual journey.

Austin writer Sarah Wimer’s work has appeared in Saturday Review, Hispanic, Vista, Latino, and the Austin Chronicle. This is her first piece for the Observer.