The Castaways

Can Galveston's black community survive the island's comeback?

photos by Ben Tecumseh DeSoto

On restless nights, the Rev. Norris Burkley Sr. drives the streets of Galveston’s North Side, counting homes with lights on. It’s his way of gauging the recovery, two months after Hurricane Ike, of this storied but imperiled African-American area. At last tally, he found just 21 lighted homes, where hundreds once glowed.

That worries Burkley, the pastor of Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church, a 136-year-old African-American congregation that draws from the area’s abundant public housing projects and aging rental homes. “People mean life, life means growth, growth means our neighborhood survives,” Burkley says. “At this point I don’t see no growth, I don’t see no life, and survival looks dim.”

Burkley, a bulky man with a regal bearing and a salt-and-pepper goatee, is standing in the gutted interior of his historic brown-brick church on a mid-November afternoon. Since the storm, he’s been living in a Holiday Inn on the seawall, working from an extended van, and waiting for the insurance money needed to repair the church and parsonage. A line encircling the sanctuary shows that the water rose to three feet inside, covering the pews, ruining the organ, and washing out the parsonage. Mold crawls up the altar.

Before Ike hit, 150 souls filled these pews on a good Sunday. Now Burkley has moved services to a Baptist church in La Marque, 15 miles away on the mainland. Only 20 members of his congregation, he estimates, have made it back to Galveston.

But the reverend is worried about more than just his flock. “People from Galveston love Galveston,” he says. “They couldn’t live nowhere else, and if they did, they wouldn’t enjoy it.”

Outside, the North Side streets are silent. “For Sale” signs poke up from the yards of flooded one- and two-story rental houses. Aside from a few liquor stores, local businesses are shuttered. The tiny African-American museum, brightly decorated with murals depicting such local heroes as Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, remains closed.

The north and south sides are roughly divided by Broadway Street, the island’s main east-west thoroughfare. During the Jim Crow era, Galveston’s white leadership made a push to uproot blacks from historically integrated neighborhoods and concentrate them in a ghetto north of Broadway. The result was the poorest and most crime-plagued part of the island. But also one of the proudest and stubbornest.

Hurricane Ike damaged about 75 percent of Galveston’s homes. But the storm wreaked extra havoc on North Side neighborhoods. Water surged from Galveston Bay into the low-lying area, flooding homes that were built decades ago under lax building codes. Meanwhile, luxury houses, many sitting practically on the beach, weathered the storm virtually unscathed.

On color-coded damage assessment maps produced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the contrast is stark. North Side structures are colored mostly in yellow and red, indicating substantial damage. Under FEMA rules, these buildings cannot be occupied and may end up being demolished. South of Broadway, on higher ground behind the 17-foot seawall, the neighborhoods are by and large tagged green and gray, indicating little or no destruction. In these neighborhoods, contractors buzz about making repairs; many residents are back in their homes.

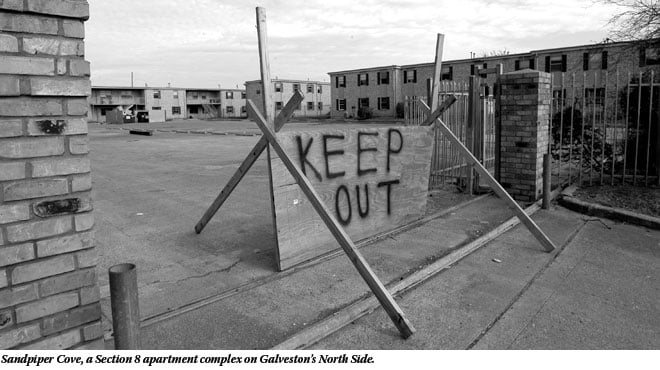

On the North Side, four of six housing projects are filled with mud and mold, fenced in and condemned by the Galveston Housing Authority. Many of their residents are now stranded in a diaspora that includes San Antonio, Austin, Houston and Texas City. Others sleep in cars, on the beach or, until recently, in two tent cities that sprang up before FEMA brought in trailers. The sudden scarcity of housing has sent rents skyrocketing. Galveston’s post-hurricane economic tailspin was compounded by the November announcement that the island’s largest employer, the University of Texas Medical Branch, was laying off 3,800 employees. (See sidebar.)

Like many on the North Side, Burkley is growing increasingly fretful about the slow pace of recovery. Despite assurances from authorities that Galveston’s poor and working-class residents will be welcomed back, many fear that long-term rebuilding plans-only now unfolding-won’t include them. The storm was bad. The aftermath may be worse.

“The big picture: Nobody knows when we’re going to start working on these projects, when we’re going to start putting this community back together,” Burkley says. “This is what we call a disaster area. Where is the money for the disaster? Can’t no one say you can survive on ‘wait for what’s coming.'”

For Galveston’s North Siders, comparisons to the grim fate that awaited thousands of black New Orleans residents after Hurricane Katrina are hard to avoid. “This is the same thing as the Lower Ninth Ward,” says Robley Cahee, a longtime North Side resident and member of Burkley’s church.

In 2005, Katrina severely damaged half of New Orleans’ affordable-housing stock. While public housing projects, subsidized Section 8 apartments and affordable private-market homes moldered in areas like the Lower Ninth Ward, authorities dithered. Ten months after the floods, in June 2006, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the New Orleans housing authority finally announced plans to demolish four large projects totaling 4,500 apartments and replace them with “mixed-income” developments that very few of the projects’ former residents could afford to move into. An estimated 82 percent of the city’s public housing was ultimately razed.

“We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans,” exulted Richard Baker, a Republican congressman from Baton Rouge. “We couldn’t do it, but God did.”

Whether or not God was involved, the result has been a permanently altered city. Homelessness has doubled. An estimated 132,000 people left town. The black population has plummeted. Public school enrollment has dropped significantly. Rents have risen beyond the means of many. And the political balance has tilted away from the traditional power base of black Democrats.

In many ways, the situation for Galveston’s low-income and working-class residents was even more dire than in New Orleans before their respective storms. The city already had a high poverty rate (more than 20 percent, similar to that in New Orleans) and more government housing than any other city under 60,000, with almost half of Galvestonians eligible for federal housing assistance. Before Katrina, New Orleans had about 14,000 units of public housing; Galveston-less than a tenth the size-had 2,200 units before Ike struck. Unlike in New Orleans, where many African-Americans owned homes, 75 percent of Galvestonians were renters before the storm, says Ted Hanley of The Jesse Tree, a social service organization. Now, he says, “The scramble to find places to live is unreal and the costs are exorbitant.”

It’s far too early to know whether Galveston will go the way of New Orleans and the North Side the way of the Lower Ninth Ward. A similar fate is not inevitable, partly because Galveston’s city government has been more functional than its pre-Katrina counterpart in New Orleans, where the chronically mismanaged housing authority had been in federal receivership since 2002. There’s also hope that the incoming Obama administration will shift HUD’s priorities to address housing shortages in disaster areas like the North Side.

City leaders have pledged to bring back their most vulnerable citizens-though, of course, there was similar talk in New Orleans. Exiling public housing residents would be an “injustice,” says Mayor Lyda Ann Thomas. “They must be allowed to come back-whether it’s a year from now or a year and a half-to new sites, which I think would be exciting,” she says. Thomas has made no promises about what public housing will look like in the future, but suggests that former residents will be first in line for “whatever new structures are built.”

Galvestonians of every background take pride in their ability to bounce back from calamity. After all, this island survived the worst natural disaster in American history, the 1900 storm, which leveled the city and killed at least 6,000 people. Every lament is tinged with a dogged faith in the island-dwellers as a special breed: resourceful, relentlessly optimistic. As one woman shouted at a recent public meeting: “We are Galvestonians and we are resilient!”

But beneath the cheerful bluster, many locals detect an ominous murmur. “All across Galveston, you hear people saying it would be a good thing if the projects were not rebuilt and FEMA were not allowed to provide trailers,” Heber Taylor, the editor of the Galveston County Daily News, wrote in a November editorial. “The idea is that the island would be a better place if the poor went elsewhere.”

Half a mile away from Norris Burkley’s church, at the Cedar Terrace housing project, Jeffery and Doris Gipson are loading their worldly possessions into a white SUV. Today is the last day for residents to get their personal belongings out. The Gipsons are on their 10th trip. Luckily, they find that nothing has been stolen, a real worry because many of the apartments have been left wide open since the storm. Their second-floor dwelling came through the storm unscathed, but the whole project has been coded red by FEMA. (The downstairs units are a mess.) Unable to afford a storage unit, the Gipsons are storing their things under shower curtains in the back yard of a relative’s small house in La Marque, where 25 people now live.

September 13, the day Ike hit, was Doris’ 46th birthday. She spent it hunkered down with her two kids, her husband and other evacuees at a school in Austin, where she took it upon herself to keep the communal bathroom clean. When some people began stealing from other temporary residents, the family went to La Marque. HUD placed them in the Disaster Housing Assistance Program, which provides temporary rental assistance, but the $1,200 monthly voucher proved as good as worthless in Galveston’s strained rental market. (In late November, the Gipsons found a Super 8 in Hitchcock that would accept the voucher.)

The Gipsons are better off than some former project residents; at least they haven’t been sleeping in their car. But they have been left in limbo. Before Ike, Doris worked at a day care center and Jeffery at a furniture store. Their income more than paid the $650-a-month rent at Cedar Terrace. But their jobs are gone; both workplaces were wiped out by the storm.

Jeffery has resorted to rummaging through curbside junk piles in search of nonperishable items. Doris has sold all her jewelry to make ends meet. She plaits hair to buy food. “I’ve cried so much it’s pitiful,” she says. “It’s like the world put us on the back burner and forgot about us.”

The Gipsons would like to return to Galveston, but they don’t hold out much hope. “I think they’re going to tear it down,” Jeffery says of Cedar Terrace. “They want the people who’ve lived here the majority of their lives to stay out. They want the tourists to come back. Move the weak out and let the strong move in.”

If Galveston’s black community fades away in the wake of Ike, it will spell the end of a remarkable story. Galveston is where the first African to set foot in Texas, a slave called Esteban, came ashore with explorer Cabeza de Vaca in 1527. The island had the largest slave market west of New Orleans for much of the 19th century-and was the birthplace of the African-American independence holiday, Juneteenth, marking the day news of the Emancipation Proclamation first reached the South here on June 19, 1865, and former slaves took to Galveston’s streets in celebration. In the 1880s, black unionists successfully fought for equal pay at the city’s docks. Not long after, the island spawned Jack Johnson, a.k.a. the Galveston Giant, the boxing champ who famously courted controversy by refusing to accept second-class citizenship. During the civil rights movement, the city produced Kelton Sams, who grew up in the Palm Terrace projects and, as a high school student, led the successful integration of Galveston’s stores and beaches in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

In recent years, Galveston’s black community has been diminishing in number, with young people and families pushed to the mainland partly by rising rents and property values. Allegations of police brutality have strained relations with the city, too. “There’s already this basis of mistrust,” says Linda Colbert, a City Council member who represents part of the North Side.

That mistrust was exacerbated in 2005, when the housing authority razed a 228-unit housing project on the North Side. The complex was replaced by The Oaks, a neighborhood of 27 island-style cottages sold to low-income buyers at reduced prices. Underwritten by the island’s three major philanthropic groups and HUD, the new neighborhood is lovely, but few former residents of the projects were able to buy the cottages.

With exploding real-estate investment in Galveston, North Siders had begun to feel as if they were being surrounded by gentrification and slowly, surely squeezed out. In recent years, expensive second homes mushroomed on the West End of the island and tony condos went up downtown, edging into the margins of the North Side. The boom thrilled the Chamber of Commerce, but it also drove blue-collar families-black, white and Hispanic-off the island. “Galveston was always kind of a working-class town, and that’s just evaporating year by year now,” says Paul Furrh, the CEO of Lone Star Legal Aid. “These hurricanes have certainly added to it.”

Too much investment is the least of Galveston’s worries at the moment. But North Side residents are keenly aware of the potentially valuable real estate they occupy. To the east lies the Strand, Galveston’s meticulously restored historic district and a major tourist draw. To the north are the Galveston wharves, home to 850 acres of shipping facilities, warehouses and two cruise lines.

North Side neighborhoods could be gobbled up by commercial interests eager to capitalize on the aftermath of a disaster. “Investors are coming in the ruin,” says Robley Cahee. Glancing around at the for-sale signs, he wonders: “What do they need this land for? Is it for gambling?”

Could be. Between the world wars, Galveston roared with mob-controlled gambling dens. The most famous spot, the Balinese Room, was built on a pier that extended 600 feet into the Gulf. Frank Sinatra and the Marx Brothers entertained during the club’s heyday. In 1957, the Texas Rangers raided the Balinese Room and effectively ended big-time gambling on the island. But casino interests and some Galveston leaders have been trying to legalize gambling since at least the 1980s, and Hurricane Ike may have been the perfect storm for betting boosters. With the twin pillars of the local economy-tourism and UTMB-in trouble, gambling interests smell desperation. The Strand Merchants Association, among others, is pushing the city to consider legalization. “Casino gambling would provide jobs, middle-income housing needs, increased tax base and a plan for beach restoration funding,” businessman Allen Flores wrote city officials in October.

Similar arguments were made in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina. Casinos had been legal there since the 1990s, but only on floating barges. After the storm casino owners and local politicians convinced the state legislature to allow gambling palaces on shore. To clear the way for a new Vegas-style economy, government officials authorized the leveling of low-income neighborhoods on suddenly valuable waterfront real estate. Homes were demolished. Property values skyrocketed. It was gentrification in overdrive.

Galveston is only now beginning to shift from the short-term business of hauling away debris, filing insurance claims and assessing damage to the thornier problem of figuring out a future. How the island will be rebuilt depends, in large part, on who will call the shots.

City council member Elizabeth Beeton, one of three reform-minded upstarts who defeated development-friendly incumbents in May elections, has loudly accused Mayor Thomas-a member of the Kempner clan, one of the island’s three most powerful white families-of abusing her emergency powers and skewing the recovery toward her friends and allies. The dispute began just days after the storm, when the mayor abruptly canceled a “look and leave” policy, in which islanders were allowed to come back for a few hours to check on their property and then required to vacate. The program caused mass chaos as people rushed to the island, and its cancellation angered citizens who were turned away.

At a council meeting in mid-November, Beeton blasted the mayor for unilaterally creating a disaster-recovery committee stocked with local business heavyweights and headed by Gerald Sullivan, a prominent developer and chairman of the board that oversees the Galveston Wharves. (No African-American or Hispanic residents seem to have been included, though together they make up 50 percent of the island’s population.) Beeton called the appointment of the committee a “usurpation” of “our democratic process.” Thomas, who speaks with palpable weariness these days, defended her authority to create special committees-seconded by the city attorney-and said the group met only once before disbanding. “You stand as judge and jury of an awful lot of people in this town,” Thomas told Beeton.

But the mayor’s actions have invited suspicion. In September, just days after Ike made landfall, Thomas traveled with Sullivan to Washington to ask Congress for $2.2 billion to help the city rebuild. Also on their agenda was a request to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to release 600 acres of land the agency uses as a dumping ground for dredge spoils. Known as the East End Flats, the property is considered one of the last, best undeveloped tracts of land on the east end of the island. Under an agreement approved by the city in May, Sullivan Interests, a company run by Sullivan’s three sons, has the right of first refusal to buy the property if the Corps releases the land-and would pay as little as one dollar for the chance to develop it.

Galvestonians are accustomed to insular politics dominated by wealthy families, but the storm has heightened the sense that the elite are only looking out for their own interests. “When you read the names of the people [in charge] and their visions, your name, your vision, is nowhere listed,” says Tarris Woods, a City Council member representing the North Side.

The gulf between many of Galveston’s leaders and its low-income residents was highlighted on a bright Wednesday afternoon in November. At the Gulf Breeze elderly housing complex, one of two public-housing projects that survived the storm with only minimal damage, Housing Authority Director Harish Krishnarao addressed a few dozen activists, displaced residents, ministers and community leaders. The gathering was billed as a “community participation event,” but as it began, some in the audience nervously anticipated an announcement on the fate of the projects.

That wasn’t what they got. Krishnarao gave a presentation that dissected Galveston’s “AMI” (area median income), touched on the nature of commodities, and featured a slide show of images of Ike’s devastation, including one of a dead dog caught on a chain-link fence at one of the housing projects. The audience was alternately bewildered, amused and upset. What they wanted to know was what would happen to public housing on the island. Krishnarao could not say. “Everything is on the table right now,” he told them. “The goal is to bring every one of the displaced families back to the island.”

The crowd wanted more than a goal. “You’ve got this meeting going on but you’re not equipped for it,” one man said. “You’re not ready for it.”

Whether the projects will be restored or demolished will depend on the results of a federal inspection of the units, Krishnarao said. He said the assessment was expected the following week, before Thanksgiving, but as this issue went to press, folks were still waiting. (In New Orleans, it took 10 months before mass demolitions were finally announced.)

The audience peppered Krishnarao with questions and complaints: Why are there fences around the projects? What will happen once FEMA assistance runs out? Why weren’t the apartments cleared of mold right away? (“The longer it sits, the worse it gets,” one man said.) Another resident said that his sick, elderly mother hadn’t been able to get a Section 8 voucher and was living in a homeless shelter in Houston. “My mother lived here all her life, raised her children here,” he said. “This is where she wants to be.”

Krishnarao urged them to consider the disaster an opportunity for a “do-over.” “Insanity is trying the same thing over and over,” he said. As a model for rebuilding, he is studying Biloxi, Mississippi.

When Hurricane Katrina swept through Biloxi, its housing authority was already transforming traditional public housing into mixed-income developments like The Oaks in Galveston. Barracks-style projects had been torn down and houses were going up. Funding came in large part from the federal HOPE VI program, a controversial HUD initiative that helped underwrite The Oaks. At the time of the storm, 374 such homes, which replaced up to 500 apartments, were near completion in Biloxi. All were destroyed. Katrina also destroyed two of the city’s six housing projects.

Bobby Hensley, executive director of the housing authority, says the storm has unleashed an affordable housing shortage. People who owned their own homes before the storm have suddenly found themselves unable to rebuild. A waiting list-recently closed-has grown to 1,000 families. The authority has tried to address the crisis by continuing its HOPE VI-backed construction spree. But problems in the credit market and sky-high insurance rates have left would-be homeowners unable to get financing. As a result many homes built last spring sit empty. Meanwhile, the sites of the torn-down projects are slated for a casino and hotels. In post-Katrina New Orleans, HOPE VI funded the destruction of several of the city’s major housing projects.

As things got heated, Krishnarao said that Galveston’s dilemma reminded him of Tetris, a video game in which different-shaped blocks dropping from the top of the screen have to be fit together in neat interlocking rows. As the game advances, the puzzle pieces fall faster and faster, until it’s impossible to anticipate the next step. It was an odd analogy, but Krishnarao seemed to suggest that the rebuilding task is enormously complicated and increasingly difficult as days and months go by. “We are experiencing that,” he said. “The sheer magnitude of the issues, the sheer scale of the issues.” The problem is bigger than Galveston Housing Authority.”

Later that evening, Rev. Burkley spoke at a town hall meeting he’d helped organize for North Side citizens to hear from FEMA and city officials. Before the anger and frustration began to flow-and it did-Burkley addressed the crowd in a prayerful voice, putting things in rare perspective.

“Our lives and our livelihood depend on this,” he said. “Amen?”

Investigative reporting for this article was supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Institute.