Fever Dreams

Fireflies dance in the scrub, and a single common paraque rises off the road, calls “purr-wee-urr” once, and disappears into the dusk. It’s early April 2004, and I’m driving through Brownsville toward the Sabal Palm Audubon Sanctuary, scouting the route so I’ll be able to drive there without getting lost when it opens in the morning.

As I approach the gates of the sanctuary, which cradles a meander in the Rio Grande, I see figures moving in the half-dark. When I roll to a halt, a flashlight beam pans the interior of my car, and a Border Patrol agent leans into the open window, smiling, and asks me where I’m headed. Behind him, I see that a dozen agents are unloading horses off a trailer while a few others assemble night surveillance gear.

I tell the agent I’m scouting for my early morning birding trip, which he seems to believe, and then I ask if he can suggest a nearby place to camp. He points me toward Boca Chica Beach at the Gulf end of the Rio Grande.

There was something fantastic about the mixture of jangling horse tack and radio chatter on high-tech, hands-free radios, night-vision gear and thorn-proof chaps. My trip to the Valley was full of these weird scenes that seemed to rise from the mist like figures in a fairy tale, like symbols from a fever dream.

In the next days I would learn that those men were part of a team of Border Patrol and Secret Service agents sent to secure the border for a visit from a VIP. I would meet that VIP, but not before I’d stood raving on the beach in my briefs at midnight, sandblasted and soaked in a tempest, trying to wrestle my tent closed, the whole wild tableau strobe-lit by flashes of lightning.

Four years later, as I read about plans to erect a border wall through the Sabal Palms Sanctuary and the University of Texas at Brownsville, the news stories seem almost to come from the same dreamscape.

Could there really be a plan to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to build a wall that won’t stop a single migrant, but will destroy hundreds of miles of irreplaceable riparian habitat for unique plants, birds, and butterflies?

Is our nation really suing its citizens to take away their homes while citizens sue the government to demand it uphold its own environmental laws?

Has the executive branch really decreed that it will build the border wall no matter what any law or court in the land might do to prevent them?

It sounds like the ravings of a madman on a storm-lashed beach in his underpants.

Before my encounter with the Border Patrol at Sabal Palm, I had made a quick scouting trip to Boca Chica. The road to the beach wound through low, scrubby forest of lotebush, ebony, and colima. At the beach, families sat grilling fresh fish while a group of three young men fired a big, shiny handgun into the scrub. On the way back, I stopped at a convenience store to get supplies for breakfast, and the television was playing the Mexican version of Big Brother-not Hermano Mayor, but Big Brother, the title in English. An ad came on for a candidate for governor of Tamaulipas while I bought donuts and bottled water. There was an aerial photo of Boca Chica on the wall. Taken in 2001, the first year in memory that the river disappeared beneath the sand before it reached the sea, it showed the massive sandbar that stoppered the river’s former mouth.

Back at the beach after dark, I pitched my tent in the stiffening breeze. My tent pegs were useless in the sand, so I used plastic bags as improvised beach anchors and weighed the tent down with camera equipment and birding books. The last words I wrote in my journal that evening, as the wind began to roar, were, “I hope I don’t blow away.” I didn’t sleep long before the lightning began, sometimes as often as three or four bolts a second. Then I felt the tent move.

The wind tugged at the tent a few times, and then it was tumbling and bouncing down the beach toward the sea, with me in it. My books and gear spilled everywhere. The tent was upside down, the poles collapsed enough to flatten it into a perfect kite shape, with me inside. I couldn’t find the door, couldn’t find my glasses, couldn’t find my car keys. Dazed and still half asleep, I felt around for a pocketknife, thinking I would cut my way free like someone in an action movie might. I finally found the door and emerged. The RVs parked nearby were rocking in the gale, but if anyone inside saw me struggling to break my tent down so I could find my keys, get into the car, and get out of the storm, they never emerged to help.

Once the poles were out, I pulled my belongings one by one from the flaccid tent and piled them into the backseat of the car. I thought I had cleverly parked on the last little bit of pavement, some eroded remnant of an old road, but it turned out I’d parked on a pad of dried silt. My parking spot, soaked as it was, had become slicker than grease, and my rental car swerved and shimmied over the mud and wet sand until it finally bucked its way back up onto the road.

I drove to the first reasonably high ground I could find and pulled off the road to sleep as best I could while the storm raged on. Lightning flashes made terrible shadows in the thorny trees all around.

At first light, I saw that I had parked at a historical marker commemorating Camp Belknap, where more than 7,000 troops from eight states were encamped during the war against Mexico in 1846. According to the sign, they also chose the spot as the first high ground above the Gulf. I survived my single night in the car, but the location had proved less than hospitable for my historical counterparts.

Although there were no encounters with the enemy, many of the volunteers suffered from exposure to the elements, thorny plants, biting flies, and unsanitary living conditions. Many died. Within six months, the camp was abandoned, the troops dispersed.

When I arrived at Sabal Palm, the rain had nearly stopped. Occasional gusts of wind blew through, rattling the leaves of the palms with a sound like a freight train. Bedraggled groove-billed anis skulked and preened, and as the last hints of the storm faded, I enjoyed the magical feeling of this special place, the last stand of a native Texas palm forest that used to line the lower 80 miles of the Rio Grande. I watched hooded orioles, great kiskadees, and Couch’s kingbirds forage around a resaca lined with blooming retama, its golden flowers and tiny leaves laced with raindrops. I followed a trail to the edge of the river and saw a vaquero on the other side coaxing his cows along with a switch, talking to them in a low voice.

I was circling back to the visitor center when four men appeared on the trail as if from nowhere, stepping from the shadowy edge of the woods. The man closest spoke to me in Spanish too fast to follow and gestured with his hand, which was missing a finger. Another man spoke up in perfect, unaccented English, asking if I knew how to get to town without crossing Monsees. I had no idea that Monsees was a nearby main street, but apparently this band of travelers did, and they also knew that’s where the Border Patrol had set up their checkpoint that morning. A local birder happened to walk by. After he gave them directions, they slipped around a bend in the path and disappeared.

A few minutes later, in the visitor center, I mentioned the Border Patrol presence the night before and was told that special operations were under way to make the area especially secure for a coming dignitary.

I spent the next two days birding around the Valley, never far out of sight of the tower-mounted video cameras and Border Patrol vehicles that sometimes give the area the feel of an open-air Panopticon.

Driving down a farm road between birding spots, I passed a young woman sitting by an irrigation ditch, daydreaming. Looking back, the scene feels like an eerie foreshadowing of a day when families who have lived on the river for generations have only a steel and concrete wall to gaze at, instead of the life-giving flow of the river.

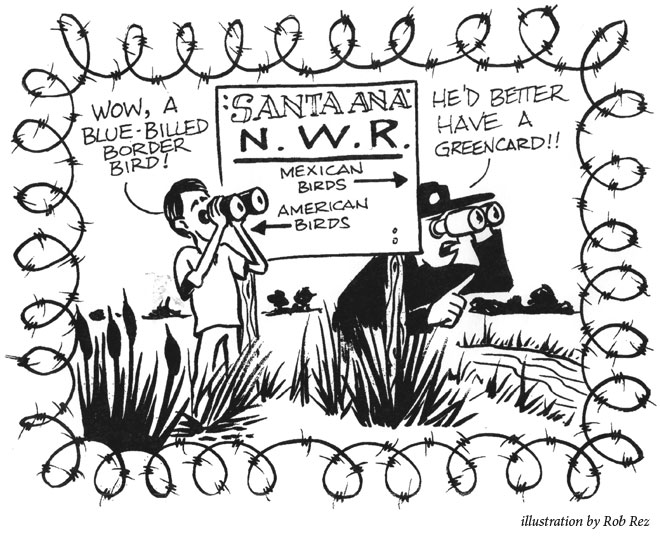

One of my stops was the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, one of the showpieces of a multimillion-dollar, multidecade effort to restore native habitat and protect endangered wildlife.

Administrators fear that Santa Ana, as federal land, will be one of the first places to see the border wall built. Clearing a swath of land big enough for a fence and an access road, as proposed by Homeland Security, will have a devastating effect on birds and other wildlife that rely on the dense cover of the river’s forests for protection. If that habitat is disrupted, the birds will likely disappear; it’s not simply a matter of flying over a fence, because they would never fly out into the open area surrounding the fence in the first place. Environmentalists are also gravely concerned that the wall would cut U.S. populations of the critically endangered ocelot off from potential mates in Mexico, putting the rare and reclusive wild cats at risk of disappearing from their last stand north of the border.

My first afternoon at Santa Ana, I joined a hawk watch that was counting migrants as they headed north. In a little over an hour, we saw hundreds of birds-Mississippi kites, Swainson’s hawks, falcons, and vultures stream north, swirling high into the sky on thermals, then peeling off in angled dives, headed north. One of the volunteers said that “fronts” of hawks are visible on weather radar and sometimes stretch to 50 miles wide. Like human migrants, they find the broad, flat plains of the Valley more conducive to travel than the Gulf or the mountains to the west. The winged migrants don’t know they’re crossing a border as they stream north by the millions every spring.

A living river is a tricky kind of border. The resacas that dot the valley along the edge of the river’s path show how much it has wandered in just the last few centuries. It would undoubtedly keep wandering now if it weren’t contained between levees and relieved of most of its natural flow.

It is possible to pretend that a river is just a blue line on a map that cuts through the land, separating one bank from the other, but nature sees a river as a vein that flows through the heart of a valley, giving life, drawing the land together.

On my last day in the valley, I returned to Santa Ana hoping for a glimpse of a clay-colored robin, a visitor from the south more rare than any of the migrants I had seen. I never found the bird, but as I was watching a Harris’ hawk perched in a tree, someone approached and asked if I would like to meet the president.

My mind scrolled through the list of living presidents, and I started to worry about the odds that it would be one I might actually want to meet when, like another mirage, Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter appeared. (He was on my short list.)

The president used my telescope to take a quick look at the hawk. Then, after a few quick but thoughtful conversations with the people who had gathered when he arrived, he climbed back into his vehicle with the Secret Service and rode off into the sunset.

At least, that’s how it would have happened in a dream. In real life, it was closer to lunchtime, and they were headed east toward the coast and Sabal Palm Sanctuary. I didn’t see any real mirages, and these scenes all make perfect sense in the chaotic, creative, dramatic context of a 21st century border town.

In the same way, the logic of building a border fence only seems like something out of a hallucination if you accept on faith the stated reason for building it: fighting an invisible invasion of terrorists and securing our borders from smugglers and the migrant menace.

The border walls in California and Arizona have already proven vulnerable to strategies as simple as a ladder, as sophisticated as acetylene torches, and as silly as bungee cords (the most famous bungee jumpers were apprehended, but there’s no telling how many bounced their way across the border without being detected).

The fence makes perfect sense if you see it as a subsidy for arms contractors, another step in the march to extend the authority of the executive branch over the courts and congress, and of course, as a shiny mirage for people who need to believe they’re being protected from invisible, omnipresent enemies: job-stealing immigrants, drug smugglers, even terror itself.

Jake Miller is the author of more than three dozen books for young people. He has birded from Brazil to Alaska.