Fighting Chances

Two Texas Senate Races to Watch

May the Best Bio Win

SENATE DISTRICT 10

Fort Worth native Wendy Davis presents a biography that Horatio Alger, or perhaps a country and western songstress, might love. Her parents divorced when she was a girl. Her mother, who had only a sixth-grade education and worked at an ice cream shop, raised Davis and her two siblings with little support from their penniless father. Davis entered the labor pool early, selling subscriptions to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram at age 14. She worked her way through high school. By 19 she had married, had a child, and divorced. She was living in a trailer park and employed as a secretary in a doctor’s office when a colleague suggested she return to school to become a paralegal. She took early morning and nighttime classes. After a year, she decided law school might be a better fit. Nobody in her family had ever graduated from college, let alone graduate school. She received a scholarship to Texas Christian University and graduated first in her class. From there she advanced to Harvard Law School, graduating with honors. Today she owns a title company and has served five terms on the Fort Worth City Council, representing the downtown area.

Davis says her background makes her a stronger candidate for her next challenge, unseating Republican state Sen. Kim Brimer. “When you come from an experience of personal struggle, you have the ability to empathize with other people,” Davis says. Her legal training, she says, gives her the analytical firepower to find long-term solutions to the problems facing Texas. Her previous races have all been nonpartisan, which has allowed her to cultivate GOP support and pursue non-ideological solutions to vexing policy issues.

But getting to the place where she can tackle those problems-skyrocketing college tuition and an overreliance on sole-criteria testing in public schools are two of her biggest issues-will not be easy. Brimer will have all the perks of incumbency, including support from everyone from trial lawyers to chambers of commerce. He will not lack for money, either. As of January, he already had more than $1 million in his campaign account. (Brimer’s campaign declined multiple requests for comment.)

Davis says she will be competitive financially. Her target budget is $2 million, and she hopes to have $700,000 by the June filing deadline. The race has captured the attention of Democratic funders like Annie’s List, which in 2007 gave her $25,000. (Several board members of the Texas Democracy Foundation, which publishes the Observer, have contributed to Annie’s List.) Davis also hopes to capitalize on a district that’s becoming more Democratic and experiencing strong African-American growth. Excitement over the presidential election should mobilize the Democratic base.

Davis was heartened by a poll released in August that showed Brimer with slightly less than 50 percent name recognition in the district. The Brimer campaign dismissed the poll results, commissioned by a Democratic activist group called The Lone Star Fund. Davis says the poll reveals “a person who has been detached from the people he represents. They know him at the chamber of commerce, but not in the community.”

Davis’ campaign and independent groups like the Lone Star Fund will do their best to define Brimer. One point of attack will be to question his ethics. The senator had long exploited a loophole that allowed him to use campaign funds to rent a house in Austin owned by his wife. The couple then sold the house at a profit of more than $300,000. The Brimer campaign will pick at Davis’ voting record on the City Council.

Expect this one to get nasty before it’s done. Davis says she’s ready. “I’ve developed a thick skin,” she says. “I know who I am and what my purpose is.” –Jake Bernstein

People vs. PACs

SENATE DISTRICT 11

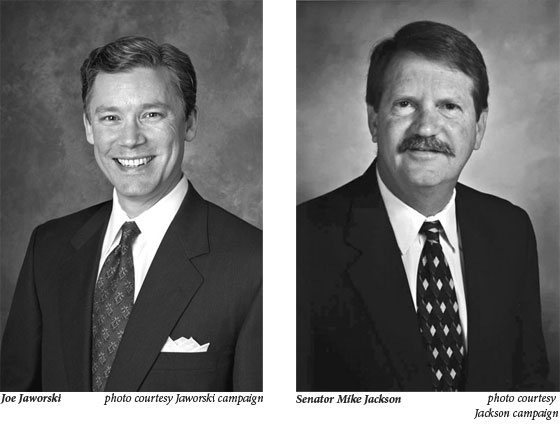

Toxic Mike” and Mike “No Action” Jackson are just a few of the names Houston state Sen. Mike Jackson’s detractors have hurled his way over the years. Democrats believe his coziness with industry and the low profile he has maintained during his nine-year Senate tenure have made him vulnerable to challenge. In particular, they point to his Senate Bill 1317, which prevented the city of Houston from using nuisance ordinances to regulate toxic emissions. Jackson’s maneuver angered residents of Houston, some of whom live in his Senate District 11, who are weary of living downwind of refinery pollution.

The Democrat who might be able to crack Senate District 11 is Joe Jaworski. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because Joe is the grandson of Leon Jaworski, the special prosecutor appointed to investigate Watergate. A 46-year-old, gregarious attorney who looks younger than his years, Joe Jaworski says residents in the district are sick of legislators like Jackson who care more about special interests than about their constituents.

Jaworski is confident he can win the historically Republican district that incorporates refinery row in parts of Brazoria, Harris, and Galveston counties. In an election year in which incumbents, particularly Republican incumbents, are on the defensive, Jaworski hopes to ride the wave of change into the Texas Senate. “More than being Republican or Democrat, voters are interested in what a candidate brings to the table,” he says. “Voters want change.”

An energized Democratic presidential race won’t hurt, either. And for the first time in more than a decade, George W. Bush won’t be on the ballot as president or governor in Texas. “There’s a real disappointment with the one-party political system in Texas,” Jaworski says.

It takes more than pocket change to win a Senate race. They now average $1 to $2 million dollars per candidate. Jaworski’s fundraising prowess has made naysayers take notice. He raised a quarter-million dollars for the Democratic primary. And he is on target to raise a million for the general election, he says. A two-term Galveston City Council member, Jaworski believes he’s ready for the big league. As for Jackson, he says in an e-mail that he is taking Jaworski’s challenge very seriously. As of January, Jackson had already raised nearly $1 million. (Jackson has received a contribution from a board member of Observer publisher, The Texas Democracy Foundation.)

A good deal of Jackson’s money is linked to chemical and energy corporations like Dow Chemical Co. and CenterPoint Energy Inc. Jackson says he doesn’t see a problem with taking the contributions because they represent thousands of individuals who live and work in his district. “A portion of the money donated to my campaign comes from political action committees to which individual employees voluntarily contribute,” he says.

“He’s got a million dollar head start,” says Jaworski. “But money won’t be the deciding factor in this race.” Jaworski plans on reaching out to Senate District 11 residents in a grassroots campaign. To learn more about what’s on voters’ minds, he’s mailed out 80,000 questionnaires. He reads some voter concerns over the phone: the Trans-Texas Corridor, the rising cost of health insurance, and decreasing air quality. “This campaign will be about us getting out into the community and really listening. Once they realize we are there to listen, I think they will respond,” he says. –Melissa del Bosque

Honorable Mentions

Houston’s state Sen. Kyle Janek has announced he will resign from his District 17 seat in early June (as the Observer went to press he had yet to do so). Several candidates from both parties are interested in running in a special election later this year to serve out the remaining two years of Janek’s term. Perhaps the most intriguing of those names is Chris Bell, the former Democratic congressman and failed gubernatorial candidate. Bell, who has returned to private law practice, told the Austin American-Statesman that he’s eyeing the race, but won’t yet commit to run.