License to Vote

The U.S. Supreme Court gives new life to the Texas GOP’s effort to pass a voter identification bill.

For sheer drama, the battle over a bill requiring Texas voters to show photo identification before casting a ballot at the polls had no equal in last year’s legislative session. Shouting matches. Angry walkouts. A gravely ill Democratic senator roused from his sickbed on a moment’s notice. Prepare yourself for an encore performance. Last month, a splintered U.S. Supreme Court upheld an Indiana voter ID law considered the nation’s most stringent.

Not surprisingly, the Court’s ruling in Crawford, et al. v. Marion County Elections Board, et al. has been heralded by voter ID supporters, who were quick to interpret the decision as an endorsement of their policy prescriptions. Within hours of the decision, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst was pledging a renewed push for passage of the bill that Senate Democrats narrowly blocked last session.

“The U.S. Supreme Court ruling is a victory for democracy in our nation, and I’m pleased the court agreed with the vast majority of Texans who want to protect the sacred American principle of ‘one person, one vote,'” Dewhurst said.

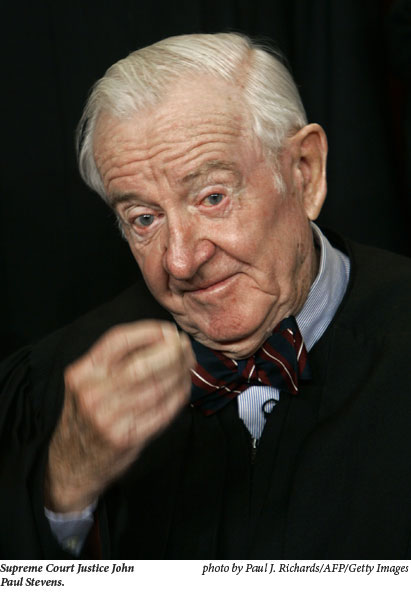

Particularly disheartening to many voter ID opponents is that Justice John Paul Stevens-oftentimes the most outspoken liberal voice on the Court-broke ranks with his ideological brethren and wrote the “lead” opinion (no opinion received a majority), which was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a concurring opinion for the Court’s hardcore conservative faction, joined by Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. David Souter issued a strongly worded 30-page dissenting opinion joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, while Stephen Breyer authored a more modest dissent.

Stevens’ defection may yet prove a positive for voter ID opponents, however, as his opinion was narrowly crafted and almost certainly not the last word on the subject. If Stevens had stuck with the dissenters, a five-to-four decision written by a conservative justice could have been more definitive. In fact, some court-watchers have speculated that Stevens’ position may have been a strategic move to prevent Scalia’s opinion from garnering a majority.

Both sides of the debate have reason to tread carefully in the upcoming legislative battles. Although the Supreme Court gave Indiana-and any state wishing to follow its lead-the go-ahead to enact stringent voter identification laws, the Court left open the possibility of legal challenges to such measures once their actual effect on the voting public can be assessed. And Stevens paid close attention to the mitigating measures of the Indiana law-such as the availability of free photo ID cards and the ability to cast provisional ballots-raising questions about the constitutionality of voter ID laws in which they are lacking.

“It’s a loss, and we’re disappointed that the Court upheld what is currently the most restrictive voter ID law in the nation,” said Wendy Weiser, deputy director of the Democracy Program at the New York-based Brennan Center for Justice, which filed a friend-of-the-court brief that was cited by several of the court’s opinions. “But the Supreme Court has not given a blank check on voter ID laws-even Indiana’s.”

In his majority opinion, Justice Stevens wrote that the Court must engage in a balancing test to determine the constitutionality of the Indiana law. On one side are the state’s interests in modernizing its election system, preventing voter fraud, and increasing voter confidence in the electoral system. On the other are the burdens that the law imposes on specific groups of voters.

Stevens took note of federal legislation such as the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which endorsed photo documents as an effective way of establishing identity. He also cited the 2005 Jimmy Carter-James Baker Commission on Federal Election Reform, an independent study group sponsored by American University, which proposed a national polling-place photo requirement. (The commission also recommended that free identification cards should be readily available and that there be a phase-in time before such a requirement goes into effect.)

Although Stevens conceded that there is no evidence of in-person voting fraud in Indiana, he wrote, “[F]lagrant examples of such fraud in other parts of the country have been documented throughout this nation’s history by respected historians and journalists.” Critics of the opinion have been quick to point out, however, that the only examples Stevens cited in his supporting footnotes were an 1868 mayoral election in New York City and one recent case in the 2004 Washington gubernatorial election.

Stevens concluded by quoting from the Carter-Baker report that the “electoral system cannot inspire public confidence if no safeguards exist to deter or detect fraud or to confirm the identity of voters.”

Stevens then weighed these benefits against the burdens that the Indiana law imposes. After dismissing the difficulties arising from “the vagaries of life,” such as loss or theft of photo identification around Election Day, he assessed the challenges confronted by those who do not have state-issued identification, such as the need to obtain required documents like birth certificates (and pay the associated fees) and travel to the motor vehicles department to get photographed.

For those who don’t have IDs at the time of voting, obstacles include having to cast a provisional ballot, then travel to the nearest county clerk’s office within 10 days in order to fill out an affidavit to explain the reason for a lack of photo ID, such as indigency or religious objections. Such requirements, the Indiana Democratic Party had argued, would create a significant hurdle for those who cannot locate the required documents or do not have the financial means to pay for them or for the trips to the necessary offices.

Stevens surmised, however, that there was insufficient evidence presented in the trial record to “quantify either the magnitude of the burden on this narrow class of voters or the portion of the burden imposed on them that is fully justified.” He dismissed much of the evidence that parties such as the Brennan Center attempted to have considered by the Court as “extrarecord, postjudgment studies, the accuracy of which has not been tested in the trial court.”

He noted, however, that the Indiana law would not pass muster “if the State required voters to pay a tax or a fee to obtain a new photo identification.” And he wrote that the burden on those without identification is lessened because “voters without photo identification may cast provisional ballots that will ultimately be counted.”

“The lead opinion said it was reasonable to permit a solution to something that isn’t a problem as long as it isn’t really burdening anybody,” Weiser said. “This leaves open the possibility that if there is better proof of a burden, then the problem … might take on greater significance.”

To see what a true victory for conservative backers of voter ID laws would have been like, one need look no further than Justice Scalia’s concurring opinion. Scalia would scrap Justice Stevens’ balancing test, and he dismissed the premise that voter-identification laws could impose a burden on certain voters as “irrelevant.” He described Indiana’s measures that allowed absentee voting and provisional balloting as an “indulgence-not a constitutional imperative.” And he warned that by leaving open the possibility of future legal challenges of voter ID laws, the majority opinion was encouraging “constant litigation.”

The legal arguments in the Court’s case mirrored the debate that took place in the Texas Legislature last year and during hearings on voter fraud held by the House Elections Committee in January-likely to be rehashed when the 81st Legislature revisits the issue next year.

Voter ID laws, according to the bill’s opponents, are a solution looking for a problem. Instances of in-person voter fraud are exceptionally rare. And even if some fraud takes place at the polling stations, it is extremely difficult to pull off on a scale large enough to sway an election. The days of truckloads of voters being ferried to polls around town with impunity-the 19th century, Tammany Hall-era New York fraud that Justice Stevens cited-are long since gone. A common concern of bill proponents in Texas is that the lack of a voter ID law permits illegal immigrants to somehow find a way to vote. Anecdotes circulated in support of these claims have been quickly refuted, and the law would do nothing to deter non-citizens who have Texas driver’s licenses or other supported photo IDs.

Meanwhile, requiring photo IDs at the polls would make it more difficult for the elderly, the homeless, the disabled, and the urban poor to vote, as they are the least likely to have driver’s licenses or other common forms of ID, and they are also the least able to navigate the avenues necessary to get them.

“Texas has a long history of voting discrimination, and that’s why there was such a visceral attack on the voter ID proposals by the minority community,” said Luis Figueroa, a legislative staff attorney for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund. “Because of the history of barriers that have been put up in places like Texas, there is concern that this is another attempt to repress minority voting.”

Democrats contend that the drive to enact voter ID legislation is, in fact, motivated by the desire for partisan advantage. As former Texas Republican Party political director Royal Masset told the Houston Chronicle last year, a state photo ID law “could cause enough of a drop-off in legitimate Democratic voting to add 3 percent to the Republican vote.”

According to Sonia Santana, who focuses on election issues for the Texas ACLU, of particular concern the last time the Legislature debated the bill was the lack of funding for low-cost photo IDs for voters without a license. Another area of concern is the state’s history of ignoring provisional ballots-a form of voting that would become much more prevalent if poll-place identification laws are tightened. Currently, only one in four provisional ballots cast in Texas is counted, well below the national average of 70 percent.

“The state of Texas is wasting its time on this,” Santana said. “As it is, we’ve already got a pathetically low turnout. Why put up another barrier when it’s just a nonexistent problem? It’s fear, hype, and racism.”

Republicans counter that in-person voter fraud is difficult to detect, so the extent of the problem is unknown. They argue that the law would inconvenience few voters, although some of their arguments turn statistics on their head. For instance, the bill’s supporters cite similar figures for registered voters and licensed drivers as evidence that every voter has a picture ID, despite the fact that licenses are available to non-citizens and those under voting age.

They also point to increased voter turnout in Indiana and Georgia following passage of voter ID bills. Outside the court after oral arguments in January, Indiana Secretary of State Todd Rokita went so far as to claim that Indiana’s law helped account for the larger voter turnout in the state in the 2006 elections.

Santana counters, however, that there’s no connection. “Obviously, you’ve got an influx of voters, elections have been tighter and the population in general has been increasing,” she said.

If the Texas House passes a new bill and the current split between Republicans and Democrats in the Senate holds up in November-or if Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst decides to label voter ID an “emergency”‘ issue and allow a simple majority to bring the bill to the floor-Texas will again be poised to enact stringent identification requirements.

“We know there’s going to be a big fight in the Lege this session,” said Figueroa. “Last year, there were 11 Senate Democrats that forced a block. And we expect our allies will still be there. Nothing’s really changed.”

The issue could be resolved with a compromise, as some states have done, by allowing voters without photo identification to affirm their identity provisionally before casting their ballots. Or Dewhurst and the Republicans could prevail, in which event a lawsuit will likely follow. For Republicans, that might not matter if a voter ID law helps them stay in power long enough to influence legislative and congressional redistricting in 2011. While the legal hurdles this time around will be higher thanks to the Court’s recent decision, any future challenge of a voter ID law-whether in Texas or elsewhere-will be supported by much more research on the effects of such laws on the voting population.

“There are a lot of studies that suggest this is a problem,” Weiser said. “The Court acknowledged that there is a body of evidence out there that might be able to substantiate this burden, but it did not come out in this case. So this is not the end of the story on voter ID as a litigation matter.”

Anthony Zurcher is a writer living in Washington, D.C. He is an editor with Creators Syndicate and editor-in-chief of Supreme Court Debates magazine.