Unconventional Wisdom

Texas Democrats endure another round of caucus chaos, and it may actually help the party.

The man who is perhaps best positioned to appreciate the ironies piled up around the ongoing Texas Democratic prima-caucus is state party Chair Boyd Richie. When Richie was elected in 2006, nobody could have predicted the wild primary season to come. In fact, during the last legislative session Richie led the charge to move up the date of the Texas primary in a bid to increase the state’s influence in the nominating process. It was a Republican, Lubbock state Sen. Robert Duncan who blocked that move, and now, as Richie puts it, the state GOP is “sitting on the sidelines watching the parade go by.”

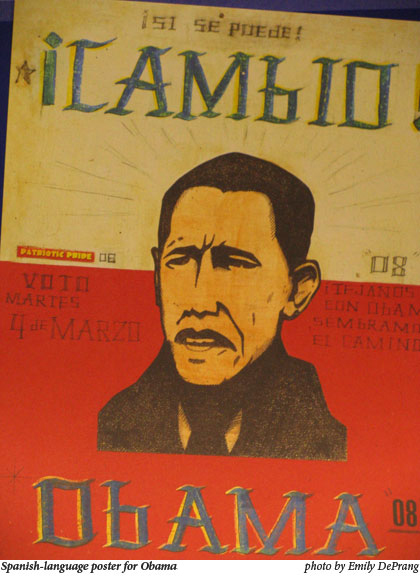

With record-breaking Democratic turnout have come unprecedented headaches. The struggle to manage that surge was once again on display on March 29 at 279 county and senatorial district conventions. It was the second step in Texas’ three-part caucus to determine how 67 delegates will be apportioned between Democratic presidential aspirants Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

Driven by excitement about the candidates and disgust with almost eight years of incompetent and corrupt administrations in Texas and Washington, about 100,000 Lone Star Democrats participated in the conventions. For the larger senatorial districts, the event took a minimum of 15 hours to complete. Some went until dawn. It was up to each county party organization to find a locale and raise the money to pay for the process. The diverse venues included a warehouse, a parking lot, and a dirt-covered rodeo arena. Almost all the conventions featured long lines and mass confusion. Caucus-goers endured stupefying boredom punctuated by heated challenges over delegates, mostly played out before credential committees. In several places, police were called to restore order.

Yet through it all most delegates seemed to remain upbeat and excited by this history-making election. “I was concerned that in fact the crush of the numbers would just be so great that folks might lose some of that enthusiasm,” said Richie. “From what I could tell it generated enthusiasm.”

Delegates throughout the state began to arrive as early as 7 a.m. that Saturday morning. Extraordinary turnout meant long lines for delegates to pick up their convention credentials. The Collin County Democratic Party couldn’t find a venue big enough and had to hold its convention a day late. In Pasadena, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers facility hosted Senate District 11 and its 1,200 delegates-five times more than had attended the 2004 convention.

In Austin, by 9 a.m. the traffic jam just to get into the Travis County Exposition Center-site of the senatorial conventions for districts 14 and 25-extended for miles. Those who didn’t want to wait in their cars parked on the roadside and walked the rest of the way. The official schedule had optimistically set the Call to Order to begin at 10 a.m. A volunteer repeated mantra-like to the crowd as it trudged in: “The check-in has been extended indefinitely.” It was still going on at noon.

The sign-in process was the most important aspect of the convention; it had to be performed correctly because the number of Obama and Clinton supporters who signed in determined the number of delegates each candidate sent to the state convention in June. For Senate District 10 in Fort Worth, the convention was held in the stands of the Will Rogers Coliseum’s rodeo arena. The setting seemed appropriate: Party officials and convention volunteers-trying to deal with a dizzying array of problems-reminded one of bull riders holding on for dear life. The convention was supposed to start at 9:30 in the morning, but the sign-in process alone took five hours.

In addition to the huge turnout, organizers across the state wrestled with too many delegates. At least 400 delegates too many turned up at the District 10 convention. One of the culprits was the sign-in sheet state party officials gave to precinct chairs for March 4. The three-part form included a space for whether the caucus-goer was elected as a delegate or an alternate. The idea was that after everybody signed in, the caucus-goers would vote to determine the delegates and alternates. After that, the precinct chair would write a D or an A next to the appropriate names. But those who signed in thought the space was provided to indicate a preference. Many voters put Ds beside their names. Precinct chairs then failed to cross them out if they were not in fact delegates.

These forms, along with supplemental sheets recording the actual delegate selection, were then forwarded to the county party. Where a precinct might be allotted only a few dozen delegates, it sent hundreds of names to the party headquarters in Austin. With only a few weeks to wok with, the party had its hands full simply compiling the names into a master list. Those entering the data didn’t want to disenfranchise anyone, so they just identified everybody who had a D by their name as a delegate. That list was then put on the Internet. On the Saturday of the senatorial convention everyone who thought they were a delegate showed up.

Adding to the sign-in chaos was the poor state of the party’s delegate list. A typical example occurred in Austin, where Deece Eckstein, a delegate and member of the credentials committee for Senate District 14, proudly wore his credential-which identified him as Delbert Einstein. Delegates competed to see who had the funniest mangled name. In Tarrant County, the list from the state party was so riddled with errors that officials scrapped it entirely and started over by combing through each precinct’s original paperwork. This organizing on the fly on convention day produced predictably chaotic results. By late afternoon, the credentials committee, working in a back room behind the rodeo ring, was so besieged by angry and confused delegates that committee members called in Tarrant County sheriff’s officers to guard the door. Everyone was kept out, including reporters.

Meanwhile, out in the arena, delegates-some of whom had already waited for six or seven hours-staged a mini-revolt. They grabbed microphones and peppered the convention chair-who was reading proposed convention resolutions-with angry comments and parliamentary inquiries. “A lot of us are getting fed up with the lack of organization of this thing,” one delegate shouted into a mic. Eventually, the chair had to stop recognizing speakers, though enraged delegates kept shouting into microphones positioned around the arena until the mics were turned off. Such hostility must have been unnerving for party officials, especially considering that the Fort Worth Gun Show was taking place in an adjacent building. “This is embarrassing,” said one frustrated Obama delegate. “This is embarrassing for Tarrant County.”

Other county conventions decided the easiest route to compiling a delegate list involved redoing the election night caucuses precinct by precinct. This further delayed the process.

During the day, the waiting and logistical difficulties took their toll. The air conditioning automatically shut off at 5 p.m. at Arlington’s Senate District 9 location at Tarrant County College’s Southeast Campus, with hours of work remaining. At Houston’s Sam Houston Race Park, it took until noon for many delegates to find their precinct’s seating areas. With some precincts inside the pavilion and others sprawling outside, the sound system failed to reach everybody. The convention adjourned at 1:30 a.m., not because delegates had finished their work, but because security asked them to leave since the park was closed. At one point, the San Antonio Fire Department threatened to shut down the Senate District 19 convention in that city because it had exceeded the capacity of the warehouse where it was held. Half of the convention ended up meeting outside in the parking lot, much to the chagrin of a wedding party next door.

In Pasadena, District 11’s leaders quickly realized that the facility had an inadequate number of women’s restrooms, so they decided that periodically, the men of the convention would simply not use the restroom so as to share space with the women. “I wasn’t sure we could pull all this off, because we had all new people,” said Doug Peterson, the district chair. “But it was really neat.”

The most surprising thing about the Senate District 25 Democratic County Convention in San Antonio was not the chaos, but the feeling of goodwill. The historic Municipal Auditorium was packed with Democrats from all walks of life-every one of them energized by two history-making presidential candidates.

Ian Straus, organizer of the Senate District 25 convention, estimated about 2,000 participants attended. “In previous conventions I chaired, I had 50 or 30 people there,” he said. “This was the largest turnout I’d ever seen.” And while the lines were long for the bathrooms and for food, people didn’t complain much. Instead, it felt like a block party, with people striking up conversations with their neighbors, friends, and complete strangers they had just met in the hallway.

Asked for his favorite anecdote from the day, state Chair Richie recalled walking out the back of the Senate District 16 convention, held at the Moody Coliseum in Dallas, to the sight of delegates tailgating. “They were just having a grand time,” he said.

Some of the delegates Richie encountered on his tour of the conventions in Dallas and Tarrant counties vowed to hold block parties to reunite with their neighbors. The need for unity after the intense rivalry between Obama and Clinton was a constant refrain. Former Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk, an Obama supporter, reminded the crowd in Austin of an African proverb he likes to recite: “Two people in a burning house don’t have time to argue.”

It’s a mantra Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee might start repeating. Jackson Lee had the distinction of being booed at all three senate district conventions in Harris County at which she spoke. The congresswoman supports Clinton, though judging by the prima-caucus votes, the vast majority of her constituents are enthusiastically for Obama. According to one African-American politico in Houston, there is already an effort under way to find a challenger for her seat in 2010.

Despite the we’re-all-Democrats-here line, there were plenty of arguments and attempts to game the system. The state party distributed an e-mail prior to Saturday with a list of convention locations after receiving reports of people calling and telling delegates from opposing campaigns that their conventions had been moved or canceled. “Both campaigns did the best they could to try and make sure that their side got there and the other side didn’t,” Richie said.

The state party also put out an advisory urging the conventions not to stack the credentials committees, which ruled on challenges to delegates, but to instead divide the membership evenly between the two campaigns. Richie said the party sent trained parliamentarians to the larger conventions to advise the committees. Where delegates treated each other fairly, the conventions seemed to move more smoothly and quickly.

In Travis County, the committees patiently worked through the problems. In precincts with too many delegates, members were told that they had to decide who would get to stay; if they didn’t, the committee would pick the names out of a hat. “People get all heated, and they want their candidate, but if you kind of force them to be fair, they’re fair,” said Reggie James, who served on the credentials committee for Senate District 25.

The mood at many Houston conventions was not as calm. All day and into the night, the delegates of Senate District 13, which met at Thurgood Marshall High School, called points of order to suspend the rules and debate the presence of a quorum, hoping to influence the delegate count. After hours of intense debate, the district’s 341 delegates were allocated the same way they had been in the morning’s tally: 69 for Clinton, 272 for Obama.

Pasadena’s Senate District 11 convention ended early by comparison, at 12:30 a.m. Before adjourning, district Chair Peterson passed around a clipboard to record the names of the 66 people still present. “From now on,” he told them, “you’ll be known as the hardest of the hardcore.”

The caucuses were long thought to favor Obama, and by 9:30 in the evening on Saturday, his campaign released a statement crowing about a projected result of 38 to 29, giving the Illinois senator a five-delegate overall advantage over Clinton in Texas. The Clinton campaign didn’t respond until Sunday, cautioning that the process wasn’t over and the numbers could change at the state convention.

Some delegates are already steeling themselves for the fight to come. At least 40 voters said they are going to file a legal claim against Hidalgo County Democratic Chair Juan Maldonado for sending “political insiders” to Austin as at-large delegates.

David Garza, a real estate investor in McAllen, said that several elderly and handicapped people waited more than 12 hours to be nominated as at-large delegates. According to Texas Democratic Party rules, these slots are supposed to be reserved for the elderly, handicapped, gay and lesbian, and other minorities to ensure diverse participation in the state and national Democratic conventions. At least 500 people, mostly Clinton supporters, were vying for these 17 slots.”There was a 90-year-old woman with a walker and several other elderly women,” Garza said. “And there were gay and lesbian voters who also waited for several hours.”

What happened, however, according to Garza and participant Ester Salinas, was that Maldonado appointed his assistant, his nephew, the Hidalgo County judge, and several other prominent community members to the at-large delegate slots. Garza said at least 50 people chanted “no” as the names were read out. As the group protested, Maldonado hastily adjourned the convention.

Three days after the convention, about two-dozen protesters gathered outside Maldonado’s office to protest what Garza called “the old political backroom deals” that selected the at-large delegates. Preston Henrichson, an Edinburg attorney and parliamentarian during the convention, defended Maldonado, telling the news media that the problems stemmed from the large number of people who wanted to be delegates.

Maldonado declined the Observer’s request for comment. Richie said that such challenges will be taken up by the state credentials committee at the state convention, set to begin June 5 in Austin. In El Paso and other places, it appears that separate elections were held to choose alternates, which would have been a violation as well. “I did hear stories that instead of having the top vote-getter be the delegate and the next one be the alternate, they conducted separate elections rather than just having one vote,” he said. “There is no question in my mind that those will be the subject of challenges at the state convention credential committee.”

About 7,300 delegates are expected to go on to the state convention. The competition for spots may grow even fiercer in June, even though by then the nomination may well be dec

ded by the votes of the remaining primaries, which will be concluded by the

. Texas delegates will be fighting for the right to go to Denver for the national convention in late August. “This really is a historic process now,” Richie said. “The first viable female candidate for president and the first African-American for president-and I think one of them will be president. People want to be a part of that. They want to be a part of history.”

Sure to be part of the state convention as well will be a debate about whether to scrap the caucus process altogether. Ironically, among those clamoring to do away with the caucuses will be first-time participants brought to the table by the very process they hope to eliminate.

Richie admits that he can see reasonable arguments, both to retain the caucuses and to eliminate them. It would certainly be easier for the party, logistically, just to have a primary. The caucuses do exclude some participants, who cannot afford to dedicate the time required. On the other hand, the party now has the names of hundreds of thousands of energized Democrats it didn’t know existed before March 4. “I think one of the things I enjoyed was that people told me that at first they were just overcome by the numbers and then it dawned on them ‘where will I get the opportunity again to see this many of my fellow Democrats face to face in one place,'” Richie said. This is true particularly in rural areas where Democrats are more isolated.

Even if the caucus system is not eliminated, Richie acknowledges the need for updating. For example, modern technology at the precinct level would help. More time between the caucus and the state conventions-a change that would have to be initiated in the Legislature-would give the party more time to organize.

At press time, Richie was trying to form a committee, likely to be chaired by Dallas state Sen. Royce West, to hold hearings around the state to gather input from grassroots Democrats. There are also plans to send a survey out to delegates statewide. Ideally, Richie would like to begin that process before the convention, although he hopes there will not be a rush to judgment in June.

“We have another two years before the next state convention, and obviously four years before the next presidential year, so whatever changes need to be made-whether they are fundamental in terms of doing away with the caucus, or retain it and change some of the mechanics-is something that we need to take our time and look at,” Richie said. “We want to make sure we get it right. I think there needs to be a very calm, deliberative approach to this.”

Emily DePrang contributed to this report from Houston.