The Safe Place

For victims of domestic violence, there's no safer city than Austin.

She didn’t see where the gunshots came from, but Estrella Rochelli knew the shooter. The Dallas police had freed her husband from jail, though she had begged them not to release him. Now he had come to kill her.

The bullets punctured her car as it idled at a traffic light. She was on her way home after an evening shift waitressing at El Chico restaurant. He must have been waiting-her husband of eight years, the father of her three daughters. She sped through the light. Her car stalled a few blocks later, and Rochelli had to bolt on foot. He ran after her, firing his gun. She zigzagged back and forth across the street. Bullets whizzed past. He emptied and reloaded three times. Eventually a bullet sliced into her back. Another shot ripped through her left side under her ribs, and yet she kept running. Rochelli saw a minivan stop in the street and it backed up toward her. She stumbled to it on wobbly legs. A young couple flung open the door and dragged her inside. They drove to a convenience store and called for an ambulance. Shot four times, Rochelli bled profusely. Lying in the store, she overheard someone say she was going to die.

Remarkably, from that moment in 1996, Rochelli’s fortunes began to improve. She survived the four gunshot wounds. Still, her husband had managed to elude Dallas authorities, and she needed a place to hide. After the hospital released Rochelli, a police officer told her about a shelter for abused women in Austin. Here, finally-after years of abuse that went ignored by law enforcement-was a turn of good fortune. For victims like Rochelli, there may be no safer city in the nation.

Austin has earned a national reputation for treating and preventing domestic violence. Key to the area’s success is collaboration among the city’s disparate players: victims’ advocates, emergency shelters, law enforcement, judges, prosecutors, and nonprofit legal-aid groups. In most other cities, these groups are turf-conscious mini-fiefdoms. In Austin, they meet monthly as a domestic violence task force.

What has emerged are innovative solutions for handling abuse: The Austin Police Department and Travis County Sheriff’s Office established their own domestic violence units. Travis County prosecutors formed specialized divisions for aiding and protecting victims of abuse. Austin set up one of the first district courts in Texas designated to handle only domestic violence cases and protective orders. And victims’ advocates teamed to create one of the largest and best-funded abuse shelters in the nation-SafePlace.

These innovations likely have saved many lives, including Estrella Rochelli’s.

Domestic violence cases are exceedingly complex to prosecute. Beneath the violence is a mix of manipulation and distrust, jealousy and insecurity. Abusers often blame their victims. And the victims-wrestling with helplessness and misplaced love-sometimes refuse to press charges. Some will recant their own statements to police or even lie in court to protect their abusers.

Handling these cases requires cops, prosecutors, and judges who understand such subtleties, who recognize the dynamics of power and control that underlie the violence, and who will work not only cooperatively with each other, but also with counselors and victims’ advocates.

In 1989, Austin Police Chief Jim Everett convened the Austin-Travis County Family Violence Task Force. It has met monthly ever since. The task force now has 19 member organizations in and out of government. It serves as a common space where law enforcement, judges, prosecutors, legal-aid attorneys, and victims’ groups can lace their efforts together. A series of progressive law enforcement leaders including Everett, a number of leaders in the Travis County Sheriff’s Office, and Constable Bruce Elfant, have devoted time and resources to the effort. The result is the kind of cooperation that few cities in the nation have achieved. (The Austin police recently even set up a specialized unit within the domestic violence division to handle the most horrific cases-a unit that police leadership credits with reducing Austin homicides related to domestic violence from nine in 2005 to four in 2006 to two last year.)

The task force has been the wellspring for the city’s other innovative approaches: creating counseling programs for batterers, pushing to ensure that defendants’ criminal histories get to judges before bond is set, and stressing the use of civil protective orders for victims.

In 1997, the task force helped marshal federal money to set up a one-stop office where victims could access many of the services they would need without driving all over town as their cases stalled in the bureaucracy. It was a place where officers from the domestic violence units of the Austin police, the county sheriff’s office, prosecutors, counselors from SafePlace, and civil attorneys could all work under one roof. They called it the Family Violence Protection Team.

The effort has proved wildly successful, though it’s not as coordinated as it once was. Last year, the Austin police tried to move the office to a more remote location. Some refused to follow, and the protection team, while still useful, is now scattered. “It’s nothing like it was,” says Jim Sylvester, a longtime member of the task force and the sheriff’s department. “It’s unbelievable how the landscape has changed in just one year. It’s not as cohesive.”

Sylvester wants to establish a Family Justice Center in Austin, modeled on a path-breaking effort in San Diego, that would mesh services for domestic violence, rape, and child abuse under one roof. It would house the relevant parts of the criminal justice system, medical staff, counselors, victims’ advocates, and private attorneys. The idea has met with resistance, and funding is uncertain. “We have a lot of people come from around the country and try to duplicate or emulate what we’re doing,” Sylvester says. “But we’re trying to take it to the next level and get that family justice center going.”

Gail Rice, director of community advocacy at SafePlace and a longtime member of the task force, points to another unique effort in Austin. The city allows legal-aid attorneys to visit the jail to sift through arrest reports and pick out cases that need extra attention. They then contact the victims to ask if they need an emergency protective order, which bars alleged abusers from any contact for up to 90 days. The process leads to hundreds of emergency protective orders a year in Austin.

Perhaps nothing sets Austin apart like Judge Mike Denton’s County Court at Law No. 4-the domestic violence court, one of the first of its kind in Texas.

On a recent Friday morning, Denton’s chambers in downtown Austin were a nexus of activity. The foot traffic resembled an in-person flowchart of domestic violence cases: an assistant district attorney, a prosecutor from the county attorney’s office who handles only protective orders, counselors from SafePlace who use a room at the courthouse to support victims when they testify, a sheriff’s deputy assigned to the court, and finally Mack Martinez, chief of the domestic violence unit for the county attorney. Denton waved Martinez in to answer a reporter’s questions. As a prosecutor, Martinez said, his biggest challenge is overcoming the reluctance of victims.

“They’re in denial about the fact they are victims of family violence,” he said. “They make excuses, they rationalize. That’s perfectly natural. Yesterday, this was the person they trusted most in the world. Last night, that person beats them. This morning, it’s difficult for them to make the shift.” Having a judge who understands these tendencies makes a huge difference.

Denton, a former prosecutor, has worked with abuse cases for years. Visitors from cities around the country have come to observe Denton’s court, and he frequently speaks at conferences and training sessions on domestic violence for judges.

As Rice, of SafePlace, puts it, “When a judge has the experience in seeing the effects of coercion and fear tactics on the victim and how that leads the victim to recant, the judge’s experience puts all that in context. It helps them understand why victims do some of the counterintuitive things they do.”

About midmorning, a defense attorney popped into Denton’s office. He wanted to obtain “nondisclosure” for his client. This allows the client to wipe clean his record of alleged abuse after completing a deferred-adjudication program. The crime was no big deal, the attorney says: “It was only a hickey.” Denton eyed the documents. Here were two men deciding whether a male abuser deserved leniency. In another judge’s chambers, the no-big-deal argument might have worked. Not here. Denton knows the law. Nondisclosure isn’t permitted in domestic violence cases. Penalties increase dramatically for repeat offenders, so wiping away offenses is counterproductive.

Denton’s court handles misdemeanor assaults up to third-degree felony cases. He dispenses numerous protective orders, which can be a valuable tool in aiding victims. In 2007, 636 orders were issued in the city. But protective orders are meaningless pieces of paper unless police and judges enforce them.

Denton gives a well-rehearsed protective order speech to accused abusers that everyone in his court has heard many times. He explains to every alleged offender that the abuser must stay two football fields from the victim or face jail. And the victim can’t undo it. “If you were arrested at her house tonight, and your defense was that she invited you over-‘Let’s talk it over’-that would not be a defense,” he says. It’s repetitive, but Denton says the speech greatly increases the effectiveness of protective orders.

The court has been almost too successful. Denton’s docket is stuffed with nearly 3,000 cases, more than he can handle. What Austin needs, he says, is another domestic violence court.

Rochelli is a small woman with tightly curled black hair cropped above her shoulders. She came to the United States from El Salvador at 16 and met her future husband while waitressing at a restaurant in New York. Her marriage was eight years of increasingly severe beatings: kicks, chokes, alcoholic rages, and insults.

When she had summoned the courage to ask for help, few came to her aid. Police in New York never seemed to care. Once, an emergency dispatcher-claiming not to understand Rochelli’s accented English-hung up on her. Another night, she called 911 and left the phone line open while he beat her, hoping someone would hear and send help. No one came. Rochelli eventually escaped New York for Dallas, where her sisters live. Her husband tracked her there, and a new cycle of abuse began. Once again the authorities offered little aid.

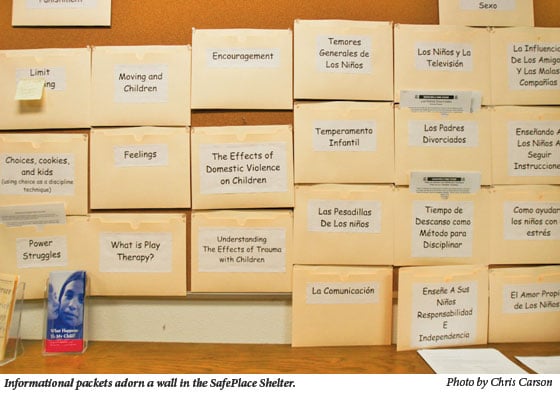

Rochelli was still recovering from her bullet wounds when she came to SafePlace with her three daughters (the shelter was then called the Austin Center for Battered Women). They stayed three months, locked behind the gates. It was more than a place to live securely. The shelter provided counseling for Rochelli and her daughters. SafePlace eventually helped her find an apartment, filled it with furniture, and installed an alarm system. Her husband, after all, was still free. “He called one of my sisters in Dallas and said he knew I was in Austin, and he was going to come and give me my last shot in my head,” she says. “I was terrified.”

Even after Rochelli left the shelter, workers from SafePlace kept in frequent contact. They provided vouchers to local stores so she could buy clothes for her daughters and prodded her to take classes at Austin Community College. Eventually she was healthy enough to look for a job. A year after Rochelli came to Austin, police in Boston arrested her husband and hauled him back to Dallas for trial.

Rochelli dreaded the thought of testifying and facing him in court. SafePlace helped her find a lawyer and sent two social workers to Dallas with Rochelli. They stayed with her throughout the trial. “I never thought I was going to make it,” she says. “I couldn’t do it on my own. [Without them] I don’t think I would have done it-too much pain.” He was sentenced to 20 years for aggravated assault. To this day, Rochelli doesn’t know why he wasn’t charged with attempted murder. The judge’s sentence made him eligible for parole after 10 years.

In the decade since Rochelli sought refuge, SafePlace experienced rapid growth under the leadership of Kelly White, former executive director, and Diane Rhodes, the current chief operating officer. (Full disclosure: White serves on the board of the Texas Democracy Foundation, which publishes the Observer). The shelter now sits on a sprawling, 12-acre campus in East Austin. First and foremost, it serves as a secure shelter. But the facility also houses an abuse and sexual assault hotline, a day-care center, and apartments where victims can live for up to two years. SafePlace directors even built adjacent low-income housing where victims can live permanently. Few shelters in the country offer the services found at SafePlace.

Perhaps its greatest feat involved coalescing the victims’ advocates in Austin. In other cities, shelters and victims’ groups have clashed over funding and other limited resources. In Austin, everyone-from victims and police to prosecutors and judges-knows SafePlace as the center for victims of domestic violence. The relative lack of discord among advocates makes cooperation between victims’ groups and the criminal justice system much easier.

When Rochelli’s husband came up for parole in 2006, SafePlace workers offered to help her write letters to the parole board to keep him in prison. Then, three months before his parole eligibility date, her husband died after a massive heart attack. She says it was a “miracle,” yet she still struggled to shake her fear. Today she works as a bartender at a downtown hotel and will soon graduate from Austin Community College with a degree in graphic design.

“I feel free,” she says. “I’m so happy now. When I came to Austin, I was feeling better and better. After all these years of being afraid all the time, it makes a big difference.” For her, the system worked. Yet the trauma from the abuse never fully goes away. She cannot tell her story without summoning the fear. Her hands shake, and she clasps them in front of her mouth to calm their movement. Tears pool in her eyes, and she looks into the distance, steadying herself. One day not long ago, she saw a man on the street who looked like her husband. “I thought that was him. But it was just a similar person,” she says. Instantly the fear flooded back.

Rochelli remembers lying on that floor in Dallas, her rescuers thinking she would soon bleed to death. She remembers hearing them, and thinking she couldn’t die, she couldn’t abandon her daughters. They have always been her motivation to escape and survive. In Austin she found the means.

Her husband had once berated her as a terrible mother. Their daughters would grow up to become nothing more than prostitutes, he said. Rochelli’s youngest daughter will enroll at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School next year; her middle daughter will graduate from there this spring. Her oldest is a freshman at Princeton University.