Baby, I Lied

Rural Texas is still waiting for the doctors tort reform was supposed to deliver.

The flood of beguiling baby photographs began cascading into mailboxes across Texas as the 2003 fall election drew near. Gracing the cover of a slick brochure, the infant smiled as a stethoscope—held by an unseen but presumably kind physician—was pressed to its chest. “Who Will Deliver Your Baby?” the mailer asked.

The direct-mail pitch was one of many churned out by insurance and medical interests as they spent millions urging voters to pass Proposition 12, a constitutional amendment that would limit the amount of money patients or their survivors could recover in medical malpractice lawsuits.

Swaddled in the glossy brochures was a dire threat. Greedy lawyers were besieging doctors with unwarranted lawsuits that were making malpractice insurance rates skyrocket. Doctors were fleeing Texas, leaving scores of counties with no obstetricians to deliver babies, no neurologists or orthopedic surgeons to tend to the ill. Without Proposition 12, the ad campaign warned, vast swaths of rural Texas would go begging for health care.

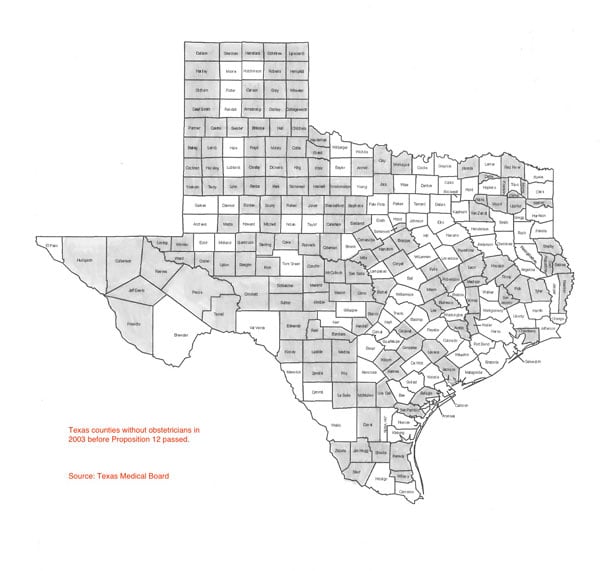

Texas counties without obstetricians in 2003 before Proposition 12 passed. Source: Texas Medical Board

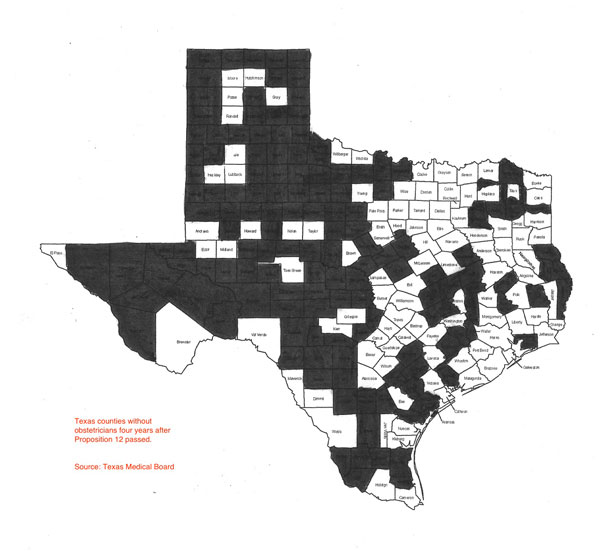

Choosing between greedy trial lawyers and cuddly babies was no contest for most Texas voters. Proposition 12 passed. Four years later, vast swaths of rural Texas are going begging for health care.

Proposition 12, and the far-reaching changes in Texas civil law that it dragged behind it, was built on a foundation of mistruths and sketchy assumptions. The number of doctors in the state was not falling, it was steadily rising, according to Texas Medical Board data. There was little statistical evidence showing that frivolous lawsuits were a significant force driving increases in malpractice premiums.

Perhaps the most insidious sleight of hand employed by Proposition 12 backers was their repeated insistence that medical malpractice insurance rates were somehow responsible for doctor shortages in rural Texas.

“Women in three out of five Texas counties do not have access to obstetricians. Imagine the hardship this creates for many pregnant women in our state,” Gov. Rick Perry told a New York audience in October 2003 at the pro-tort-reform Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. “The problem has not been a lack of compassion among our medical community, but a lack of protection from abusive lawsuits.”

The campaign’s promise, that tort reform would cause doctors to begin returning to the state’s sparsely populated regions, has now been tested for four years. It has not proven to be true.

Since Proposition 12 passed, insurance companies—many grudgingly—have lowered their rates. More doctors are coming to Texas, as a recent New York Times article trumpeted. That is proof, say Proposition 12’s backers, that so-called tort reform is working.

“Texas has seen a tremendous success in luring doctors to practice in our state thanks to tort reform passed in 2003,” says Krista Moody, Perry’s deputy press secretary. Moody noted that the Texas Medical Board is having to add staff to handle a backlog of doctors applying for state licenses.

Those doctors are following the Willie Sutton model: They’re going, understandably, where the better-paying jobs and career opportunities are, to the wealthy suburbs of Dallas and Houston, to growing places with larger, better-equipped hospitals and burgeoning medical communities.

On a Texas map inside the beguiling-baby mailer, blood red marked the 152 counties in Texas that did not have obstetricians in 2003. Rural doctor shortages were kept front and center as the state’s physicians, led by the Texas Medical Association and the Texas Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, campaigned for Proposition 12.

A flier printed by the TMA in English and Spanish and posted in waiting rooms across the state told patients that “152 counties in Texas now have no obstetrician. Wide swaths of Texas have no neurosurgeon or orthopedic surgeon. … The primary culprit for this crisis is an explosion in awards for non-economic (pain and suffering) damages in liability lawsuits. … vote ‘YES!’ on 12!”

As of September 2007, the number of counties without obstetricians is unchanged—152 counties still have none, according to the Observer‘s examination of county-by-county data at the state Medical Board.

Nearly half of Texas counties—124, or 49 percent—have no obstetrician, neurosurgeon, or orthopedic surgeon. Those specialists aside, 21 Texas counties have no physician of any kind. That’s one county worse than before Proposition 12 passed, when 20 counties had no doctor.

The TMA counts 186 new obstetricians in Texas since Proposition 12 passed, and President Dr. William Hinchey offers that as proof of tort reform’s effectiveness.

No independent study has shown what caused the increase, though Texas medical schools have graduated increasing numbers, by the hundreds, of physicians every year since 1997, the earliest year for which TMB posts data. And the state’s growth probably played some part. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Texas’ population grew 12.7 percent between 2000 and 2006, compared with 6.4 percent for the country as a whole. The number of obstetricians in Texas increased only 4.27 percent over the same six years, including three years under tort reform.

More telling is where the new obstetricians—and neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons—decided to go.

The Medical Board’s latest obstetrician data for the 254 Texas counties reveals that several counties led the gains.

Collin County, the Dallas suburb that is the wealthiest in Texas in terms of per capita income, gained the most obstetricians. Its 34 new ones increased its obstetrician ranks by an impressive 45 percent since Proposition 12 passed.

In second place is Montgomery County, Houston’s northern neighbor along the booming Interstate 45 corridor, and the state’s fourth-fastest growing county, according to the U.S. Census 2006 estimate. Montgomery gained 19 obstetricians. Tarrant County followed with 17.

Next, at 12 each, are Galveston and Hidalgo counties. Among the rest, a few counties gained in single digits, a few lost, and the majority of counties—two thirds—remained the same.

With well-equipped, well-staffed hospitals, plenty of colleagues, and insured patients, it’s not hard to see why Collin County would attract the most obstetricians or offer them the most jobs. Collin’s population grew 42.1 percent from 2000 to 2006; the county encompasses Plano, Carrollton, and a small part of Dallas.

The county’s Presbyterian Hospital of Plano alone has 73 obstetricians and 30 neonatologists for newborns. Two allied hospitals serve nearby Allen and Dallas, and the three are far from Collin’s only hospitals.

Margot and Ross Perot gave $6 million last October to the Presbyterian Hospital of Plano for maternal and infant care. The Margot Perot Center for Women and Infants has been named “Best Place to Have a Baby” by DallasChild magazine 11 years in a row. The Presbyterian system has even been honored locally for its baby sign-language classes.

The pattern of doctors’ opting to practice in more affluent, urban areas holds true for Texas’ overall gains in neurosurgeons (36) and orthopedic surgeons (185) since 2003.

The number of neurosurgeons statewide increased 8.8 percent in the past four years. The biggest share, again, went to Collin County, which gained seven. Bexar and Harris counties each gained five, while Lubbock gained four, and Tarrant, three. At last count 216 counties, or 85 percent, have no neurosurgeon.

Texas has added 185 orthopedic surgeons since 2003, a 10.3 percent increase. Harris County gained the most with 25, followed by Dallas County with 21, Tarrant County with 19, Travis County with 16, and Collin County with 15. There are no orthopedic surgeons in 169 Texas counties.

Texas counties without obstetricians four years after Proposition 12 passed. Source: Texas Medical Board

Surely, state leaders and the TMA knew that tort reform wouldn’t deliver doctors and specialists to rural Texas.

The persistent struggle to get rural, underserved Texans care by obstetricians, brain surgeons—any specialists—has little to do with lawsuits or high premiums.

Rural health care has been strained by a steady, decades-long migration of Texans from rural to urban areas. Rural areas have fewer hospitals and facilities, and tend to have higher concentrations of patients on Medicaid. “The enormity of Texas … can serve as a great obstacle for those seeking and providing health care,” TMA’s own Web site notes. “Approximately 15 percent of Texas’ population lives in rural counties, yet only 9 percent of primary care physicians practice there.”

It’s hard for an obstetrician to make a living in Deaf Smith County in the Panhandle, or Pecos County out west. Understandably, most specialists choose financial security over scraping anxiously by—if for no other reason than to pay back medical school loans. They like to practice near a large community of colleagues, have access to more elaborately equipped hospitals, and treat patients with private insurance coverage.

Yet some of those who pitched Proposition 12 as a cure for rural health care woes now seem surprised that doctors aren’t surging into the countryside.

“You limited your line of questioning to a single issue we have not yet revisited,” said an e-mail sent by Jon Opelt, spokesman for the pro-Proposition 12 Texas Alliance for Patient Access, when asked about the rural obstetrician situation. The alliance represents more than 200 insurance companies, hospitals, medical clinics, doctors’ associations, and nursing homes. It donated $500,000 to the political action committee, Yes on 12, in 2003, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Dr. Charles W. Bailey Jr., a plastic surgeon who was TMA president during the Proposition 12 campaign, said he wonders if perhaps new doctors aren’t out there and the Medical Board simply hasn’t been able to keep up its count. “They have a lot of stuff to do, and maybe they haven’t really reassessed all the counties,” Bailey said. “We have to realize that many of these counties have so few people in them, they won’t support a specialist. They’ll have family practice physicians delivering babies. Like many towns won’t support a neurosurgeon or plastic surgeon or cardiologist. I would just, I don’t know if they’ve really, with all the applications they’re processing, if they have the time and manpower to really determine, to do another head count. From all I’ve heard, they can be hard pressed to keep their head above water.”

Medical Board spokeswoman Jill Wiggins expressed confidence in the agency’s count. Fortunately, she said, the 2003 Legislature boosted its funding and allowed the agency to add staff. When the board’s license applications became backlogged in 2006, Wiggins said, the agency received even more new funding and now has about 142 full-time employees, compared with 101 seven years ago, a 41 percent increase.

Dr. Ralph Anderson, a University of North Texas obstetrics and gynecology professor and legislative adviser in 2003 with the obstetricians and gynecologists association, said the overall statewide increase in obstetricians might still yield a trickle-down effect in rural areas.

“If you bring more obstetricians to the state, a portion of those are going to go into the underserved areas, the Rio Grande Valley. If you have a lot of personalities coming in, they will disperse themselves to the area where they feel comfortable,” he said. “The more people interested, the more chance you’ll find somebody who’s looking for that kind of opportunity. Those communities have benefited because of the increased numbers of people coming into the state.”

So how did doctors become poster children for the sweeping tort-reform agenda pushed by the business and insurance lobbies in 2003?

Former TMA lobbyist Kim Ross recalled his firing just before the 2003 legislative session. Ross, who now runs his own public relations firm for national and regional medical clients, said he was canned in December 2002 by the TMA under pressure from Perry.

“There was a strongly held belief that I was personally responsible for TMA endorsing (Democratic nominee) Tony Sanchez over Rick Perry,” said Ross. “I definitely took the fall on that.”

The doctors’ Democratic endorsement had resulted from Perry’s earlier, unexpected veto of a bill they had supported requiring prompt payment from health maintenance organizations. “Perry vetoed that in an ambush without any warning. There was a huge response from physicians,” Ross said. The governor also was unhappy, Ross said, because he and other TMA staff were then negotiating with trial lawyers over what they would and would not support in 2003 tort-reform legislation.

Though they fired him under political pressure, Ross said, he doesn’t believe TMA supported tort reform’s claims of bringing health care to rural areas just to gain Perry’s favor. “There’s always been an article of faith, even among OB-GYNs themselves and family practitioners, who are the mainstay of rural practice, that if we just had some liability relief and less fear of lawsuits, that would translate into a restoration of access,” Ross said. He characterized that belief as an “urban myth.”

Yet “the cost of liability is a relative fraction of rural healthcare cost—it’s a high part of trauma [emergency] costs—but access is driven by reimbursement,” Ross said. “Reimbursement from Medicare, Medicaid, commercial managed care … You need some liability stability, but the primary driver is the economics of reimbursement. For all its emotional charge of fairness, liability cost for the most part is not the issue.”

Why did physicians readily believe it when insurance companies blamed greedy, out-of-control plaintiff’s lawyers for high liability rates in 2003? One reason may be that the largest malpractice insurer in Texas is their own.

The TMA and the Legislature created the Texas Medical Liability Trust in 1978 as a self-insured trust solely for TMA members. The trust’s doctor-insureds elect a board of directors via mail-in ballot every three years. Besides insurance, the trust provides defense attorneys to doctors who are sued, and pays doctors’ expenses when the investigators of the Medical Board fine them.

The trust is not regulated by the Texas Department of Insurance. As former Insurance Department Associate Commissioner Birnie Birnbaum noted, the trust can charge what it chooses, whi

e regulated companies must charge the

rates they file with the department. (The trust isn’t Texas’ only unregulated malpractice insurer; “risk retention” insurers are also free of state oversight. There’s no federal regulation of insurance companies.)

Since 2003, the trust has reduced its insurance premiums: 12 percent in 2004; 5 percent in 2005; 5 percent in 2006; 7.5 percent this year; and 6.5 percent for 2008. In 2008, the trust will charge doctors 68.7 percent of the charge before tort reform.

Dr. Donald A. Behr, head of TMA’s rural physician group, speaks enthusiastically about his rural practice in Graham, seat of Young County in North Central Texas. Behr and his wife, a nurse, left Fort Worth six years ago and say they love treating the smaller community of neighbors and friends, “not just insurance cards.”

Graham’s hospital is better off than most rural facilities, said Behr, a general surgeon. An old oil town, Graham was flush with millionaires 25 years ago; their philanthropy keeps the hospital afloat.

Of the five counties bordering Young, only one has an obstetrician. Graham has one, but no neurosurgeon, orthopedic surgeon, or cardiologist. Specialists ride in weekly or monthly, like pioneer circuit riders, from Wichita Falls, Mineral Wells, and Abilene.

Graham Regional Medical Center draws from Jack, Stevens, Throckmorton, and Archer counties. “Part of that is because of our obstetrician, part probably because of me,” Behr said.

A frantic edge comes to Behr’s otherwise confident voice when he describes the hospital’s financial fragility despite philanthropy.

“Most of the obstetrics patients in rural Texas are Medicaid,” which pays rural physicians less than urban ones, he said. Just to offer obstetrics, Graham’s hospital has to jump through a few hoops.

First, the hospital has to have a minimum of two doctors who deliver babies and accept Medicaid, Behr said. Fortunately, Graham has three family practice physicians who also provide obstetrics to back up its lone obstetrician.

“A little hospital with one doctor doesn’t fly,” Behr said. “You’ve got to have anesthesia, and if you don’t have enough volume for a full-time anesthetist, you can’t have obstetrics, basically.”

Graham’s hardworking obstetrician sees patients six days a week, traveling to five towns, and his nurse-practitioner sees the women at other times.

In an interview, Behr scarcely mentions liability insurance as a factor facing rural health care. Adequate reimbursement—getting paid—by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers to cover costs topped Behr’s concerns, expressed in a long conversation.

“The only way to keep doctors in rural Texas and anyplace is, somehow we have to find a way to practice medicine cheaper,” he said. “We spend too much, yet there’s a lot of doctors who can’t make a living.”

Tort reform may have failed to brighten health care for rural Texans, but two state agencies are trying to lure physicians and other health care professionals to underserved areas.

The seven-year-old Office of Rural Community Affairs gives doctors stipends of up to $15,000 a year for residency practice after medical school in underserved areas. A separate program in the state office uses $112,500 a year in interest from the state’s share of the massive tobacco lawsuit settlement to recruit and retain licensed nonphysicians, such as nurses and physical therapists, in underserved areas. Another $2 million in tobacco money is distributed by the office to small rural hospitals.

The 2007 Legislature increased funding for a doctor education-loan repayment program administered by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. For the current biennium, the program will hand doctors $1 million annually.

Loan program Director Lesa Moller said doctors willing to practice in underserved areas can receive up to $9,000 for each year they complete. After two years, the doctor becomes eligible for federal matching funds of up to $18,000.

“Unfortunately, there’s been way more applicants than there’s been dollars,: said TMA lobbyist Helen Kent Davis of the assistance programs, adding that the TMA has advocated for the rural programs at the Legislature for many years.

TMA does not fund any rural doctor programs, Davis said.

The irony that tobacco-settlement money is put to work year after year sustaining rural health care professionals and hospitals should not be lost on Texas physicians who campaigned for Proposition 12.

The massive tobacco settlement was the work of trial lawyers, the very folks TMA leaders demonized in their quest for cheaper insurance and fewer lawsuits.

Suzanne Batchelor is a freelance writer in Austin.