Texas (Still) Needs Farenthold

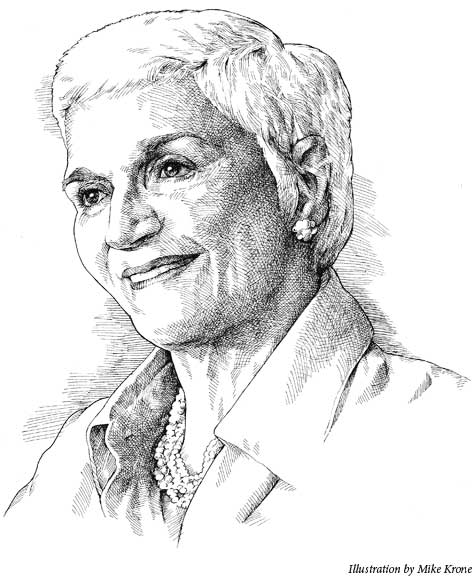

Sissy Farenthold’s hair is the color of lightning, just the shade to match her scruples. She’s got that risky, spark-and-crackle itch for The Square Deal that marks the radical. She has the radical’s great, essential gift-she reminds you of the future, but not the future that springs to mind in these dour days. Sissy recalls the sort of future we imagined in finer times. It’s the first of her happy contradictions, and is perhaps why I find myself reaching wildly into the past for comparisons. Sissy is, for starters, a South Texas Katharine Hepburn; she’s Eleanor Roosevelt as imagined by Vogue, with a splash of FDR’s patrician twinkle; she’s Battling Bella Abzug without the bite. Though there’s no mistaking her political seriousness, “politician” seems too beige and bureaucratic to describe her. “Adventuress,” with its wide-brimmed dash, seems closest to the mark. When Sissy sweeps into the lobby of her Houston high-rise in a slanted sun hat and faux-leopard sneakers, even going to lunch is filled with pioneer glamour.

Houston is the place for passing fancy. It’s a city of fickle attachment, so it follows that I’d have to leave it, have to move as far away as Manhattan to find Frances “Sissy” Tarlton Farenthold-a lady made of sterner stuff than the Shamrock Hilton, a legend that, unlike Sissy, stands no longer. I am 27 years old. Farenthold’s last political race-for governor against incumbent Dolph Briscoe-was 33 years ago. So it’s through no fault of my own that I missed seeing firsthand Farenthold becoming, in 1972, the first woman nominated for the vice presidency, finishing second to Tom Eagleton as George McGovern’s running mate. Or that in 1971, as the only woman in the Texas House (den mother of the Dirty 30), she helped expose the Sharpstown scandal. Or that she was the face of Texas liberalism for a generation, heading pluckier campaigns than anybody since the late U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough.

I found Sissy while trawling through history, and then in the telephone book, because somewhere during the second term of the second Bush presidency, I needed to look for reasons to be proud of where I’m from. Like many before me, I was seized by the idea of Farenthold. For the past 40 years, she’s served for the state’s idealistic youth as a near-cult symbol of the Texas that might be. That’s true even though she found herself “un-electable” as Sharpstown faded from public memory and the novelty of good government wore thin. She refused to even consider, in 1973, what public interest groups assured her would be a surefire run for Congress. “What I discovered,” Farenthold told me, “was that political office was a life of constant moral compromise. And I didn’t enter politics with the purpose of compromising my morality.” It has never been Farenthold’s reputation to equivocate.

I am aware of the prevailing view of Farenthold-that she’s downbeat, shy, and sober; a “melancholy rebel” was Molly Ivins’ phrase. Of course, Farenthold has always had the kind of social conscience that can sometimes run amok. If it’s not death row, then it’s apartheid. If it’s not El Salvador, it’s Iraq. The night before our meeting, Farenthold hosted a teen-rehab fundraiser; the night of the interview, she emceed a Palestinian film festival. It’s one thing to talk about honoring the holiness of every sentient being, but I’m sure that in practice it can get pretty depressing. So her fleeting moments of mournfulness don’t shock me. What does shock me (it’s another of her riddles) is how she can remain so wholly honor-bound and still be a real good time. “Sissy’s a bombshell. She’s a hell-raiser,” says Liz Carpenter, no slouch when it comes to weighing fiery figures, “but she’s a likeable hell-raiser.” So if Farenthold’s other achievements ever wither, if she ever fatigues of fighting global wrongdoing, she can always fall back on being terrific at lunch. Which is exactly what this Hockaday-finished, frontier daughter of three Lone Star founding families-the Bluntzers, the Doughertys, and the Tarltons-was born and bred for. Years before Ivins’ sobriquet, Farenthold was the Barefoot Debutante of Corpus Christi’s society page.

“Politics just seems to take over everything,” she sighs over lunch. It’s in the small talk, the joking, the family stories. Yet nothing about her seems typical of a Texas politician (she’s posh and polished; by Houston standards, she’s practically Parisian)-nothing except her storytelling. Then she’s John Henry Faulk in a Dior dress. We’ve driven in my rental car (which is, she says, “much larger than my Prius”) to a shady spot to dine on Montrose Boulevard. It’s the Saturday the art cars come to town. The most dazzling, ludicrous vehicles (beaded and fish-tailed, tin-foiled and festooned) are passing mere feet from our banquet, and I can’t take my eyes off Farenthold-who at 80 seems more marvelous than anything on the street. Her face, her fingers, her Irish eyes, and white-water voice are quick in a way that has nothing to do with speed, and make all the more fantastic the fact that she is telling stories about having been invisible: “The day after my first election to the Legislature [in 1968],” she says after we’ve both settled on heaping salmon sandwiches, “they had a party for me in Corpus, and a man came up to me and said, ‘Mrs. Farenthold, I had the pleasure of voting for your husband yesterday.’ And I said, ‘Well, thank you very much, but I think you’ll discover that you voted for me yesterday.’ And then he became very disturbed and said, ‘Well hell, if I’d known that I never would have voted for you.’ And then he walked away.

“A few months later, I read in the newspaper that the governor [Preston Smith, a Lubbock movie theater mogul] had told a group of Democratic women from Michigan, ‘I feel that I can say in all confidence that within 10 years, a woman will be elected to the Texas Legislature.’ And I was in the Texas Legislature,” she says with such outrage her iced-tea practically joggles from its glass. “I was in the Legislature; Barbara Jordan was in the Legislature. So the next morning, I marched right into the governor’s office so that I could introduce myself.

“And then, after I was nominated for vice president, in the papers the next day, there was barely a mention of it. It was like it never happened … as though it had been completely obliterated … stricken from the record.”

Her righteous anger has run dry, and it’s as though she still can’t fathom such broad-scale bad manners. “And that’s one of the moments when I really got it, really got a glimpse of what women were up against. … Because even if you were nominated, even if you got elected, you still weren’t there.”

Farenthold frames the story of her life in such moments-forming a narrative of slow turning from her cosseted, Catholic girlhood toward activism: of losing a young son and learning to organize for safer playgrounds; of her “soul-searing experience” as legal aid director of Nueces County, suddenly exposed to the inattentions (and worse) of the state; of being invited, on the eve of the filing date, to run for the Legislature and not accepting before asking her husband’s permission; and of being baptized into radicalism at a Palm Sunday labor march in Del Rio. “I think I was the only Anglo woman there,” she says. “I gave a short speech, and then there was a peaceful march through town. We were all holding palm fronds, and as we walked, I looked up, and the rooftops were lined with gunmen who’d been deputized by the local sheriff, pointing rifles down at us. … It was terrifying … like a police state. And this was America … and I realized I’d been living in another country all along. … I decided if I ever wrote a book, that’s what I’d call it. The Road to Del Rio.”

This is how Farenthold frames the story of her life, but I have trouble buying it, because it’s difficult to believe that such radical change could be founded on a series of epiphanies gathering steam, rather than on something fundamental to a person’s character-on a sort of predilection to rowdiness that doesn’t photograph too well. How many Corpus debs, barefoot or otherwise, were awaiting invitation, in the spring of 1970, to march down that road? Glance through Farenthold’s photos, and her life’s turn is unmistakable-from an almost Victorian bride, posed on a veranda and surrounded by children in coordinated sailor suits, to That Woman in the ’70s, of whom a confounded Walter Cronkite sputtered over the airwaves, “Some lady from Houston wants to be vice president.” This is a point I press with her over a pile of apricot tarts, making sure to mention that I know all about that Ramada Inn sign-about how, in her early 30s, she sued the local government to enforce a statute preventing businesses from cluttering the Corpus coast with big, ugly signs; about how she pursued this case all the way to the state Supreme Court, and won. (I maintain that if somebody had only told Gov. Smith, House Speaker Gus Mutscher, and Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes the story of Farenthold and the Ramada Inn sign back in the ’70s, they might well have refrained from the blatant crookedness that comprised the Sharpstown scandal. Those boys had no idea whom they were dealing with.)

Farenthold leans back, grins, and grips her chest with her fingertips. “Well,” she says, “there’s always been something inside me-so that I just can’t help myself.” Then she tells a story of having been offered a lift to Houston from Washington by then-Vice President George H. W. Bush, a journey intended to conclude in the customary fashion for those guests aboard Air Force Two with a brief photo op consisting of a handshake and a thank you-precisely the type of facile formality Farenthold has spent her life resisting. “And all the way up through that reception line, I was telling myself, Don’t ask about first nuclear strike, don’t ask about first nuclear strike, and then, what’d I do? I could not help myself.

“I remember my aunt, years ago, sent me a book. With a zebra-print cover. I Married Adventure. Oh, I liked the sound of that,” she says, gazing somewhere beyond me. “And now,” she says with a stretch, tossing down her napkin, “I have to go home and figure out what I have to say about Palestinian film.”

Robert Leleux’s first book, The Memoirs of a Beautiful Boy, will be published this January by St. Martin’s Press. He lives in New York City, and misses Houston.