Ralph Yarborough’s Ghost

Fifty years after his election to the senate, many overlook his legacy, but the 'Patron Saint of Texas Liberals' still has something to teach a new generation.

A few years after being defeated in his final run for the U.S. Senate in 1972, Ralph Yarborough found himself sitting in a driver’s education class in Austin. James Nowlin, Yarborough’s friend and former aide, doesn’t remember exactly what landed him there, though Yarborough reputedly had a heavy foot when he was behind the wheel. Regardless, Yarborough sat in a room filled with younger people. None of them, he told Nowlin, had any idea who he was other than “just an old guy who was there.”

“That always boggled my mind,” said Nowlin, now a federal district judge in Austin. “His name was on the ballot every two years for many years, many elections.”

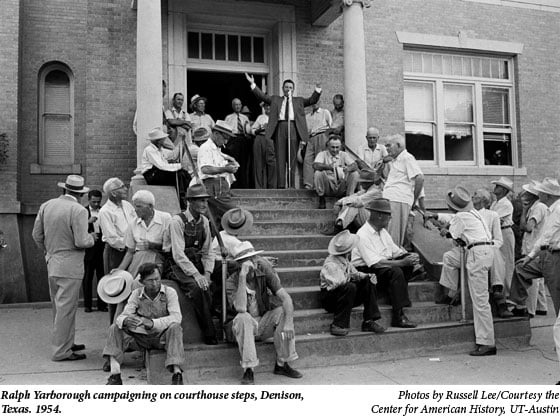

Indeed, before serving as U.S. senator from 1957 to 1971, Yarborough ran unsuccessfully for governor (back when Texas elected a governor every two years) in 1952, ’54, and ’56.

Even before his name became commonplace on Texas ballots, Yarborough made headlines. In the 1930s, as an assistant attorney general under mentor James Allred, Yarborough pursued big oil companies that neglected to pay royalties on oil pumped from public lands. His legal victories channeled millions of dollars into the state’s Permanent School Fund, which continues to help fund public schools.

As a senator, and privately until his death in 1996, Yarborough achieved dozens of policy successes. He was the only Southern senator to vote for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and one of three to support the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He co-authored the Cold War G.I. Bill. He helped President Johnson pass much of the Great Society legislation.

Yarborough was renowned for his support of environmental legislation and was directly responsible for the creation of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Padre Island National Seashore, and Big Thicket National Preserve in Texas.

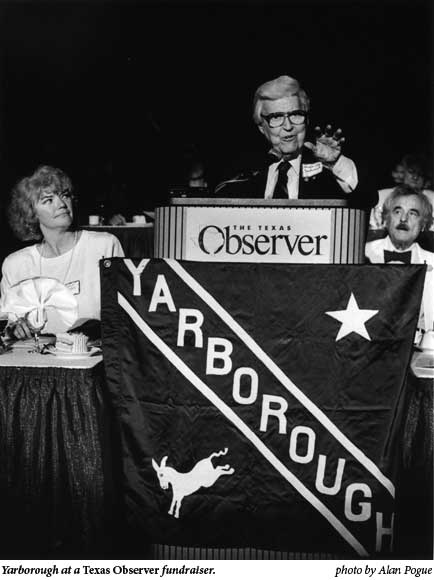

An affable campaigner renowned for his populist style and his ability to cross-reference a library of books in his head, Yarborough became an important progressive role model. His campaigns were a classroom for some of the most successful Texas liberals of the last three decades. Yarborough proved that Texans would elect an unabashed liberal, someone who, as Ronnie Dugger, The Texas Observer‘s founding editor, has remarked, had “hard-gut conviction.” Fifty years after his election to the Senate and 11 years after his death, Yarborough’s legacy remains relevant in this deeply red state, especially to younger liberals who may have never heard his name uttered in their Texas history classes.

Yarborough campaigned wearing a suit when the primary elections were held in the summertime-and he wouldn’t take his jacket off. Campaigning meant preaching politics from the steps of every county courthouse. Yet Yarborough thrived. He did it with wit, passion, showmanship, and compassion.

“The old campaign was sweat and grit and shoe leather,” said former Yarborough aide Joe Pinnelli.

Pinnelli met Yarborough during one of his campaigns for governor, when Pinnelli was a young boy in Stephenville. He watched as the women in the house fried chicken in anticipation and, around lunchtime, a motorcade pulled up.

“The very distinctive thing that I remember, being 8, is that he came to me and shook my hand, and he said, ‘How old are you?’ And I told him,” Pinnelli recalled. “And he said, ‘Well, you will be old enough to vote one day.’ … And sure enough, you know, I ended up old enough to vote for him.”

Pinnelli also ended up old enough to work for Yarborough when the politician ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1972. By then, Yarborough was nearly 69, but his energy still surpassed that of volunteers in their early 20s. “Whoever went on the road with him came back just completely and totally spent,” Pinnelli said.

Jim Boren, another former aide, remembers Yarborough at his peak. In the summer of ’56, Boren showed up at Yarborough campaign headquarters with “two weeks of vacation and a station wagon.” By the end of the campaign he was manager, a position he kept when Yarborough ran for Senate the following year. Boren, an author and retired professor at Oklahoma’s Northeastern State University, remembers the courthouse circuit in those years well: “We had some boys that played music, and they were called the Cass County Coon Hunters. So we would send that team, those musicians, country-style music, ahead to get the crowd together as he was coming in from the last stop. … As he was coming into the edge of town, they’d say, ‘Here, he’s coming now!’ So we’d get the crowd all excited, and then they’d take off for the next town.”

Then Yarborough would speak. He would preach against the state’s conservative Democratic establishment with a booming voice and a populist message. He preached about “putting the jam on the lower shelf so the little people can reach it,” though he wouldn’t use those exact words until his 1958 senatorial campaign.

Yarborough’s voice would become so strained after a day on the trail that Boren packed lemons in his briefcase. “He’d cut a lemon, and he’d squeeze it, and he’d suck on that lemon as a means of helping keep his vocal chords strong,” Boren recalled. “He used those lemons to good effect.”

Yarborough’s political success required what Pinnelli described as “oceans of volunteers,” particularly since he had far fewer major donors than did his opponents. It was more than charisma that attracted many of his closest supporters. For many, it was his bookish grasp of history, an intellectualism upon which he based many of his policy decisions, that earned him their respect.

Yarborough was a voracious reader. His former administrative assistant, Gene Godley, remembers him as a “bibliophile” who would stay up scanning book catalogs and reading in his library until all hours of the night. “Probably outside of the University of Texas, it may have been one of the best Southwest libraries,” Godley said. “He had the most incredible cross-referenced mind. He knew his library, he knew his books and would pull out related passages that would occur in various history books.”

Caryl Yontz, Yarborough’s receptionist in Washington for more than five years, recalls that the senator’s reputation for being well read was acknowledged by his Senate colleagues as well. On one occasion, Yontz said, Sen. Eugene McCarthy-whom Yarborough later endorsed for president because of McCarthy’s opposition to the Vietnam War-stopped by the office to drop off a copy of his latest book of poetry. “He said to me, ‘I’m giving this to Ralph because he’s one of the few senators who reads,'” Yontz recalled. “And, I mean, he did!”

Yarborough’s passion for history, especially Texana and Southern history, had deep roots in the senator’s small-town, East Texas upbringing. That background, while crucial to Yarborough’s populist success, brought with it internal conflict as the senator reconciled his progressive politics with his more conservative cultural roots.

According to Patrick Cox’s biography, Ralph W. Yarborough: The People’s Senator, some of Yarborough’s “most influential” memories from his childhood included conversations with former Confederate soldiers. Having grown up under segregation, and knowing intimately the culture subscribed to by many of his constituents at the time, Yarborough’s consistent votes in favor of civil rights legislation resulted from difficult deliberation, Nowlin said.

“I don’t think he ever wavered, what he knew he was going to do, or what he thought he ought to do in regard to those votes,” Nowlin said. “But it did cause him some angst.”

Yarborough’s cultural roots were reflected in his “old style,” as Garry Mauro, former Texas General Land Office Commissioner, also an aide to Yarborough, termed it: “He thought of women as secretaries,” Mauro recalled, “even though when you look back, he had some of the brightest women in American politics working for him, and they did have positions of responsibility.”

At other times the senator was more direct: “He didn’t ever cuss in front of us [women],” Yontz said. “But he cussed in front of the men.”

If Yarborough’s old-fashioned character seemed to conflict with his progressive stands, it also contributed greatly to his campaign style. His passionate intellectualism, coupled with his approachable East Texas demeanor, translated into a magnetism that helped make Yarborough’s political career.

His intellectual, yet down-home, campaign style wasn’t the only thing that won over voters. Clifton McCleskey, who taught government at the University of Texas at Austin and University of Houston during Yarborough’s time in the Senate, said the senator was a liberal by the standards of the day, but that he also campaigned on issues such as veterans’ rights that carried wide appeal across ideologies.

“It wasn’t all just the liberal creed. He was able to talk about and deal with things that either straddle those lines or had very little ideological orientation,” McCleskey said.

Still, Yarborough’s commitment to liberalism was strong enough to make his name synonymous with the liberal wing of the Texas Democratic Party. Indeed, McCleskey said, Yarborough’s election to the Senate was an affirmation of the liberal wing, ultimately hastening the state’s party realignment.

Gary Keith, a political science professor at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, has a similar assessment: “Yarborough’s political legacy is that he served as the bridge from the old Southern Democratic Party of elitism and racism to the nationalized Texas Democratic Party-a party with a base in labor and with open membership.”

Yarborough was a leader of the liberal Democratic faction in the days when the Texas party was led mostly by conservatives and Dixiecrats-among them Gov. Allan Shivers, who, along with Gov. John Connally and LBJ, backed Republican Dwight Eisenhower in the 1952 presidential election.

“I mean hell, we’d have riots on the [Texas Democratic Convention] floor,” remembered Chuck Caldwell, a Yarborough aide who worked for his gubernatorial campaigns in the 1950s. “The credentials committees that were run by Shivers and Connally and these people would take legal delegations of ours and throw them in the street.”

At least partly because of Yarborough’s election in 1957, the liberal wing of the party began to gain a foothold-eventually so-called “Yarborough-Democrats” came to represent the mainstream of the party as conservatives slowly crossed over and became Republicans.

By 1982, the year former Yarborough staffers Ann Richards, Jim Hightower, and Garry Mauro were elected in a Democratic sweep of statewide offices, the Texas Democratic Party was disagreeing over details. “They weren’t throwing chairs at each other like they used to,” recalled Caldwell.

Mauro said the 1982 sweep could not have occurred without Yarborough. Sure, Mauro and others elected that year were either supporters or former aides of the senator, but Yarborough’s election to the Senate had laid the foundation by helping align the party with labor: “By the time ’82 rolled around, if you didn’t have labor support, you couldn’t win,” Mauro said. “Now, did anyone call Yarborough and ask for advice?” he said. “Hell no, he’d keep you on the phone for two hours.”

Yarborough’s influence was not always obvious, nor was he alone responsible for the success of the liberal Democrats. While many liberal campaigns in the last half of the 20th century included people who had cut their political teeth working for Yarborough, those workers had also been inspired by many other liberal leaders and organizers of the era. But Yarborough may have been the most inspirational.

To his armies of aides and supporters, Yarborough represented not just a bright man of impeccable character, a grassroots populist with a great capacity for public service. He represented not just good ideas and the liberal agenda. Yarborough represented hope-hope that Texans could and would elect liberals.

In the 1980s, the voters did so again. But those victories, now more than two decades old, ring hollow to younger generations who, like many back in 1957, have grown accustomed to the leadership of conservatives.

“After our people took over in ’82, why that ended up being the high-water mark for liberal officeholders in the state of Texas,” Caldwell said. “And George Bush’s crowd moved in just about 10 years [later], and what do we have in the state now?”

Few believe, in the ever-evolving and increasingly costly maelstrom that is Texas politics, that Yarborough’s shoestring, courthouse-step campaign tactics can woo Texas voters today. But many who remember him well believe the fundamental trait that got Yarborough elected can be used again-McCleskey called it Yarborough’s “willingness to dare.” Mauro called it his “courage to buck conventional wisdom.” Dugger termed it tenacity and unshakeable conviction.

“He lost, lost, lost, and won,” Dugger said. “Tenacity. That’s the only thing that will withstand the pressures from the big money now.”

With Texas once again dominated by conservative leaders, many of Yarborough’s old supporters are looking back on the hope the senator once gave them as solace that liberals can rise again. And their gaze is directed at the generations who never knew Yarborough, hoping they have the tenacity to bring a change.

“He gave us a sense that this can happen in Texas,” said former state Rep. Sissy Farenthold, who ran unsuccessfully for governor alongside Yarborough in his failed 1972 Senate campaign. “And maybe a lot more will [happen] before this story’s over.”

A recent graduate of the University of Texas, A.J. Bauer is an intern on the business desk of The Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Massachusetts.