Swamp Fighters

Laredo environmentalists marshal their forces to save an improbable wetland

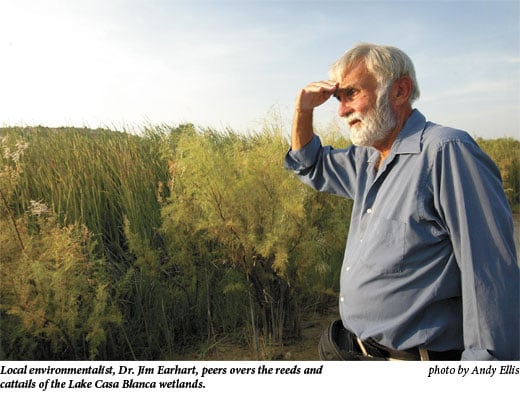

On a soggy July afternoon, the air lousy with mosquitoes, Jim Earhart squishes through an ecological irony: a wetland in Laredo. Earhart, a 71-year-old retired professor of biology at Laredo Community College who moves with the vigor of a man half his age, lets the place speak for itself.

A dense thicket of bright-green sedges and man-high cattails rings a pond where turtles, tadpoles, and fingerling black bass lurk. Along one edge, roots submerged in shallow water, a thick grove of slender black willows and enormous, ancient-looking palms casts shadows over the thorny huisache and mesquite typical of South Texas scrubland. The pond drains into a small stream that melds into a finger of Lake Casa Blanca, a popular birding destination and the area’s only notable body of water other than the forsaken Rio Grande. A brightly colored snake slithers away from footfalls before it can be identified.

Several inches of rain had fallen the day before, causing widespread flooding in the city and swelling the wetland with turbid runoff and a smattering of trash. Earhart points out a nest of sticks lodged high in a tree-the once and perhaps future home of the regal Swainson’s hawk, a migratory raptor that winters in South America. Blue herons, white pelicans, cormorants, and egrets ply the muggy air.

Over this landscape looms its potential destruction. A mountain of soil, four stories high, waits for bulldozers to shovel it into the wetlands and create a clean, flat surface for a $120 million shopping center.

City officials sold 88 acres, including the wetland, to Mission, Texas-based Merchants Holding Co. and are on board with its plan to build the Laredo Town Center. The city initially leased the 88 acres to the company for 40 years in 2005. Two years later, when a decade-long moratorium on the sale of airport land expired, the city decided to sell. Merchants Holding was the sole bidder, offering $15.86 million, just $5,000 over the city’s minimum asking price. In a strange twist, the developers are suing the city for failing to deliver clear title to the property. Merchants Holding claims that controversy over the wetland destruction is jeopardizing its chances of obtaining a needed permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Once it gets that permit, local environmentalists fear, there will be no way left to save a small but precious oasis.

The Everglades this is not. The Casa Blanca wetland is all of 20 acres and lies but a stone’s throw from a busy highway and the Laredo International Airport. On a satellite-generated map, it looks vulnerable and insignificant. On the ground, the hubbub of a border city’s explosive growth is within earshot. In fact, the wetland owes its existence to humans. The construction of Lake Casa Blanca in 1951 and the diversion of storm water from the airport into a detention pond created this riparian environment. Now nature has taken hold here. In turn, the wetland has taken hold of Laredoans.

Saving this meager, man-made wetland in a dry stretch of the country has sparked the closest thing Laredo has seen to an environmental movement. Teachers, fishermen, bloggers, doctors, and college students have gathered thousands of petition signatures, packed public meetings, taken to the local airwaves, and bugged lawmakers and regulators to halt the bulldozers. The outcry has given hope to both environmental advocates and reform-minded citizens-a usually frustrated lot in Laredo-who believe it is time to shake up the city’s business-as-usual political culture.

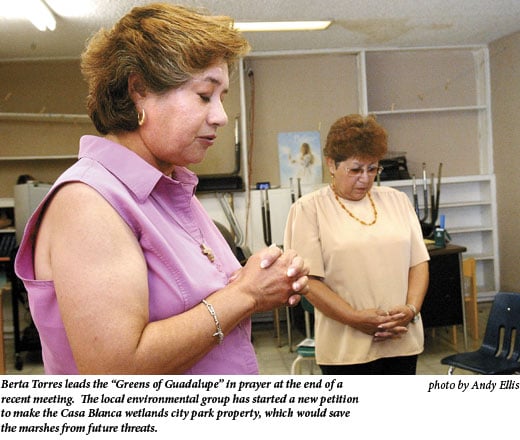

“The whole city is waking up. It’s amazing; it’s beautiful,” says Berta “Birdie” Torres, a middle-aged woman with a gap-toothed smile who lives with her elderly parents and runs a pet-sitting business.

Faith drew Torres to the wetland cause, she says. A visiting priest from Chicago stirred her soul with his teachings on the Catholic concept of Earth Care. “He changed the way we thought,” she says. “He said God gave us the Earth. It’s our mother, and we need to take care of it.” In March Torres and fellow members of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church formed the Greens of Guadalupe and began the slow task of educating themselves about the environment.

When Torres saw photographs of the threatened wetlands, she felt a call to action. Never politically involved before, she joined Earhart, who had been her professor in 1984, and others in a petition drive that has collected more than 12,000 signatures opposing the destruction of the Casa Blanca wetland. The Laredo City Council, the Corps of Engineers, the EPA, and various lawmakers have received copies.

In mid-April Torres went before the Laredo City Council to ask that the wetland be saved. “This is a beautiful place, a beautiful place,” she said, choking up. “How can you think of destroying it? I don’t know what you are thinking. But I tell you, people like me, they’re not going to allow you to do it, they’re not going to allow it.”

In a border region wracked by intractable environmental problems, the wetland may seem trivial. Earhart, an admirer of eco-agitator Edward Abbey and naturalist Aldo Leopold, has taken on bigger foes. Over the years he’s criticized the Border Patrol for the erosion caused by its ever-expanding riverside patrol roads, pushed city hall to locate industry away from the toxics-laden Rio Grande, and once had to suffer through an appearance in Laredo by Tom DeLay during which the former House majority leader casually proposed eliminating all vegetation along the Rio Grande in the name of border security. In the early ’90s, Earhart cofounded Laredo’s sole environmental nonprofit, the Rio Grande International Study Center, to aid the long-suffering river.

“Everybody would joke about the turds floating out of the creeks into the river, especially in Nuevo Laredo. There was kind of a general feeling back then of, what can you do, what can you do?” Earhart says. Earhart’s retirement dream of becoming, as he puts it, a “wandering cowboy”—sailing the seas or traveling South America—has been postponed time and again as new battles beckon. Things have improved—they don’t laugh at him at city hall anymore—but he’s grown weary of the struggle. The fight to save the wetland is probably his last rodeo, he says.

Nevertheless, Earhart feels optimistic that at long last his side has a fighting chance. “I think to win this, to stop the filling of the wetland, could be a real catalyst for organizing the community,” he says. “I mean, 12,000 signatures on a petition in Laredo is historical. I’ve never heard of that before. I think it could open up real possibilities.”

It helps that the wetland’s fate has become inextricably linked to that of 1,656-acre Lake Casa Blanca. Once a drive into the country for Laredoans, the lake and the Chacon Creek watershed that feeds it are swiftly becoming engulfed by subdivisions and businesses. “The wetland plays such an important role for the lake as far as acting as a biological and mechanical filter from the airport,” says George Altgelt, a young attorney who makes his living suing developers who build in flood-prone areas. “Saving the wetland is a component of saving the lake itself.” In a town that has a pitiful number of parks and recreational facilities, but a large number of poor people, the lake is a beloved natural asset.

“Lake Casa Blanca is where the working guy gets to take his family, meet his compadres on the weekend, do a little carnita, maybe do a little fishing with his kids,” says Richard Geissler, a community activist.

Laredo’s reformers and environmentalists share Earhart’s view that stopping the bulldozers is about more than this small patch of wetland. “For a lot of people, this wetland is their Waterloo,” Altgelt says. “They’re saying this city has slashed and burned long enough and it’s got to stop.”

Remy Salinas says, “This community needs an environmental victory. It really does.” Salinas, a bearish man who returned to Laredo in 2005 after a 30-year absence, swept back into town with a plan to shake up the old guard. A former commercial pilot, he got himself appointed to the city’s Airport Advisory Committee and then landed a spot on the Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee. Salinas is also a regular on a popular radio talk show, the Jay St. John Morning Show, which airs on weekday mornings.

Salinas speaks in martial terms of his planned minirevolution. “If we fight, we can win this war, one battle at a time,” Salinas says, sipping a cappuccino at Starbuck’s. “But you have to have a victory. You can’t just lose, lose, lose, because otherwise, in a community this fragile, people will throw up their hands and say, what can we do?”

The wetland protectors hope to win this round by convincing the Corps of Engineers to force developers to shield the unique ecosystem. Barring that, Salinas hints at a “legal smear campaign” to scare potential retailers from the shopping center. The Rio Grande International Study Center is also raising money for a legal defense fund.

There are longer-term plans, too. Earhart and the reformers are gathering signatures for two citizen initiatives that could go before the City Council. One would put teeth into a 2004 green-space ordinance. The law was supposed to limit development around bodies of water, but has so far done little to change old habits in Laredo. The city claimed a grandfathering exemption on its own land in the case of the Laredo Town Center. The other initiative would call on the city to set the wetland aside as a park. The reformers are also thinking about offering themselves up as “back-to-basics” candidates in the next municipal elections.

If this is an environmental and civic awakening, it comes deep into Laredo’s boom times. Fueled by international trade and immigration, Laredo has for more than a decade been one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation. Inevitably, such growth has proved to be double-edged.

“NAFTA is really the root cause of a lot of the environmental problems we’re experiencing, but it’s also produced our economic prosperity,” Salinas says.

He faults city government for failing to manage the trade agreement’s effects. Local officials, he argues, have rubber-stamped developers’ plans without asking for anything in return. “The developers are planning our city, and they have for a long time,” he says. One result is that the watershed has been drastically altered. Creeks are routinely filled, rerouted, or lined with concrete; homes and businesses are then built on top or nearby, leading predictably to worse flooding. “Dr. Earhart has seen this coming for 10 years, and they’re thinking they need to build an ark,” Salinas says, laughing sardonically at the council.

The wetland imbroglio ignites anger because it squares with the perception that politicians are unresponsive to citizens. But the trick is showing people in a town with very low voter turnout and an atavistic indulgence of the old patron system that civic activism can work. Salinas has a brutally utilitarian view of how to do that. “If we lose this battle, I want people to see the blood,” he says. “If we lose, people are going to watch-whether they like it or not-them bulldoze the wetland. That’s when the pain’s going to come.”