Capitol Offense

Child's Play: Foster Care's Fiasco

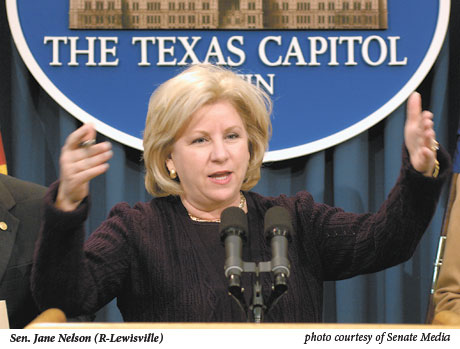

On February 22, the House Human Services Committee met to consider how to repair one of the most fractured parts of the state bureaucracy—its care of foster children. This might surprise the casual observer. You may have heard that state lawmakers fixed Texas’ ailing Department of Child Protective Services two years ago. You may remember that in 2005, following a string of news accounts detailing gruesome deaths of abused children, Gov. Rick Perry declared the crisis at CPS an “emergency issue” for the Legislature. The resulting reform legislation infused the agency with $250 million in new state money and reorganized or privatized several CPS functions. Many political observers hailed the CPS reform as one of the Legislature’s great successes in recent years. When the bill passed, Sen. Jane Nelson, a Lewisville Republican and one of the bill’s architects, declared, “This legislation will ensure that the agencies responsible for making life-and-death decisions are properly equipped and trained to make the right decisions.”

Well, not so much. Two years on, CPS has improved in some respects, but the agency is once again foundering. And as the Human Services Committee convened its meeting in the Capitol basement in late February, lawmakers were again faced with media reports of grisly and preventable deaths among foster children. Some children’s advocates say the latest round of reform bills may make the situation even worse.

Joyce James, an assistant director of CPS, was the first to testify before the House committee, chaired by Patrick Rose, the young Democrat from Dripping Springs. Many of the lawmakers on the committee are new to the issue of child protective services, and they began peppering James with questions about how the agency functions.

Though CPS’ mission is straightforward enough—take care of abused and neglected kids—the agency’s machinery is fairly complex. The department performs two main jobs: Investigate families it suspects abuse or neglect kids, and care for children removed from their families. Once a kid enters the foster care system, CPS finds the child a permanent home—either with relatives or a foster or adoptive family, or in a facility. CPS caseworkers guide the child through the bureaucratic maze—representing them in court, to family members, whatever’s required—until the minor enters a safe, permanent home.

Before 2005, the investigative piece of the agency caused the controversy. Severely understaffed CPS investigators failed to remove several children from parents who later injured or killed them. In one infamous incident, a Plano woman sliced off her 10-month-old daughter’s arms with a kitchen knife while chanting religious hymns; four months earlier, CPS had deemed the woman’s mental state “stable.” Other similarly gruesome tales forged the political will for change. In the 2005 CPS reform—filed as Senate Bill 6—state lawmakers allocated $250 million to beef up CPS’ investigations unit. That part of the bill has been reasonably successful. The agency hired more investigators; caseloads among CPS workers dropped; and the crisis seemed to pass.

As James told the committee, CPS has another crisis arising from the other half of the agency’s mission: foster care. Paradoxically, the department now removes children from dangerous homes more frequently, but the kids potentially face new harm once under the care of the state.

In 2005, state lawmakers provided scant new funding for the foster care side of the CPS mission. With most of the new money earmarked for investigations, SB 6 offered a panacea for the foster care side of CPS—privatization.

Under the 2005 bill, the Legislature directed CPS to privatize all its foster care placement and adoption services. Private companies already handled 80 percent of current foster care placements and adoptions—SB 6 mandated the privatization of the remaining 20 percent. The most radical piece of SB 6 privatized all the oversight work currently handled by CPS caseworkers. The children’s lone advocate in the system was supposed to be replaced by private, in some cases for-profit, companies. Private providers would represent kids at every stage, even in state court. CPS would retain legal responsibility for kids completely in the care of private companies.

CPS planned to test this privatized design in the San Antonio area before taking it statewide. But in fall 2006, just as the agency put out a request for private bidders in Bexar County, a new flood of CPS horror stories put the plan on hold.

In late November, the Dallas Morning News reported on the deaths of two young children that CPS had placed with private foster care agencies. In Corsicana, a young child died of head injuries in a foster home. The company that placed him there—Mesa Family Services—had been cited by CPS for more than 100 safety violations, yet the agency had renewed Mesa’s contract three months earlier, the Morning News reported.

With such lax oversight, it didn’t seem like such a good idea to turn the state’s foster care and adoption system over to private companies like Mesa. Stunned by the reports, Sen. Nelson directed CPS to put all privatization on hold in November. That’s where it stands. “The department is waiting further instruction [on privatization] from the Legislature,” James told the House committee.

Meanwhile, CPS child placement remains a shambles. James conceded after a question from Austin Democrat Elliott Naishtat that the foster care system is so overwhelmed at times that CPS can’t find a temporary residence for some kids. Instead, the kids stay with CPS caseworkers in their offices for three and four days. There was a stunned silence in the room. Here was the agency lawmakers had famously fixed last session admitting that foster kids are sleeping on couches in state offices.

A few minutes later, Scott McCown testified before the committee and explained why CPS sometimes stashes kids on office sofas. McCown is a former state district judge and heads the Center for Public Policy Priorities, an Austin-based policy shop. The problem with CPS, McCown told the committee, is lack of resources.

Texas ranks 47th nationally in per-capita funding for child protective services. Just to reach the national average—not the top, just the average—Texas would have to spend $2 billion more every two years. (That’s nearly 10 times the ballyhooed $250 million increase from 2005). With too little cash in the system, CPS can’t recruit enough foster care providers. A shortage of safe places to house kids forces CPS to work with just about any company available, no matter how shady their record. Worse yet, meager state funding also means CPS has a shortage of caseworkers and other oversight staff to monitor how kids are treated in foster homes and treatment facilities.

Then McCown got to his main point: The solution to these problems is more state funding, not more privatization. He said privatizing the remaining 20 percent of foster care services that the state now provides accomplishes nothing and wouldn’t save any money. The 20 percent of kids the state places in foster care account for the majority of adoptions in Texas. Moreover, the logistics of shuttering state-run foster care and shifting the kids to private firms would, in fact, cost money, roughly $17 million in state funds, McCown said.

Beyond that, privatizing the jobs of CPS caseworkers is “what the private providers were able to talk the Legislature into, and I hope you will revisit,” McCown said. Private companies can offer some valuable services, he added, but should “Joe’s Foster Care” decide what happens to Texas’ abused kids? “Do you want to say that a private company will decide if a child goes home or not?” he asked. McCown offered an analogy: If an overworked shepherd is looking after too many sheep, you hire more shepherds. “You don’t say, this shepherd is doing a bad job, losing some sheep, let’s hire the wolf.”

At that point, an annoyed Chairman Rose spoke up. “I’ve agreed with most of what you’ve said today. I don’t know that I’d compare the private providers to the wolf.”

“Yes,” McCown said. “This Mesa Family Services home that was shut down, I would compare to the wolf.”

McCown recommended that the Legislature allow CPS to privatize certain services when that makes sense, but not to mandate privatizing CPS case workers. A bill filed by Naishtat (HB 1361) would make CPS’ privatization optional.

Sen. Nelson also has a foster care reform bill. Her proposal would beef up state oversight of foster care homes like Mesa, but it would also follow through on some of the privatization from 2005. Nelson’s bill, as filed, would privatize all foster care services, and it would initiate a pilot program to privatize 10 percent of CPS caseworkers.

For their part, private foster care companies—the wolves, in McCown’s view—are lobbying hard for more business from CPS. Recently defeated state Rep. Toby Goodman, the Arlington Republican who helped write much of the privatization language in the 2005 bill, is now lobbying for its main beneficiary: Providence Service Corp., a large, Arizona-based foster care company that last year bid on the initial CPS contract in San Antonio. Goodman and daughter Christie have reportedly been shopping a bill to lawmakers this session that would establish a fully privatized foster care system—including privatized caseworkers—in the San Antonio area as a pilot program. Whether Goodman’s proposals make it into Nelson’s bill remains to be seen—it may come up for a hearing in Senate committee in early March.

Upon filing her CPS bill in early February, Nelson said in a statement, “We are clearly not where the Legislature intended two years after passing SB 6.” Indeed, the question remains: Will the Legislature’s continued experiments on the state’s foster care system make it better or worse?