The Spies of Texas

Newfound files detail how UT-Austin police tracked the lives of Sixties dissidents

“Even a paranoid can have enemies.” — Henry Kissinger

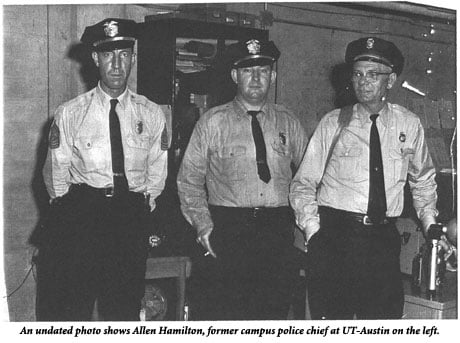

Allen Hamilton kept his files secret until his death in 2005, long after his retirement as campus police chief for the University of Texas at Austin. His son discovered them while cleaning out his father’s office. The boxes of documents and photos from the 1960s included records of the most horrific event in Chief Hamilton’s tenure—the August day in 1966 when Charles Whitman perched atop the UT Tower with a high-powered rifle, killing 15 and wounding 33. Graphic photos from the Whitman archives were made available to newspapers to mark the 40th anniversary of that bloody day.

But Hamilton’s files also provide valuable links to the complex political and social currents that were washing over the campus four decades ago. These documents—made public here for the first time—tell the story of how the University of Texas spied on its nonconformist and dissident students. The records—covering a period from approximately 1963 to 1970—show the extensive efforts that campus police made to identify, watch, and follow students and faculty members whom it found suspicious.

The files include more than 500 pages of department memos, some from student informers; lists of names of campus “dopers” and activists; and photocopies of newspaper articles and leaflets. Also included are over 250 surveillance photographs. The documents reveal that among the subjects campus police were monitoring at the time were Janis Joplin, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Richard (“Kinky”) Friedman.

Some notes are jotted on torn scraps of paper. Others are typed memoranda to the chief and reports from Hamilton to campus administrators. And there are names, lots of names, probably close to a thousand. Some typed, some scribbled, some photocopied from petitions and sign-in sheets collected at meetings and rallies.

These materials provide a window into a unique era, a formative period of creativity, iconoclasm, and growing political consciousness that would evolve into a major social movement, one in which Austin played a significant role. They show how the authorities reacted—often overreacted—and how little they really understood about what was happening in the streets. Much of the material focuses on SDS (the Students for a Democratic Society), an organization that became a force on campus and was the heart of the antiwar and New Left movement in Austin and throughout the country.

The files on SDS reveal the names of two student informers: one, Jeff Gardner, was a treasurer of the local SDS chapter, though not a significant leader in the group. The second, John Economidy, was editor of the Daily Texan, the UT student newspaper. There are signed memos to Chief Hamilton concerning SDS activities from both of them. Gardner provides detailed accounts of SDS meetings and functions, factional splits, national policy, and the comings and goings of members.

Economidy was an archconservative. Kaye Northcott, a former Observer editor, recounted Economidy’s initial appearance at the Daily Texan in the first issue of the Austin underground paper The Rag in October 1966. He “made a grand entrance into the (Texan) office wearing an Air Force ROTC uniform and carrying a makeshift swagger stick. He marched to the copy desk, banged the stick on the table rim, and announced, ‘General John is HERE!'” Economidy ran the Daily Texan—a newspaper that rabble-rousing editor Willie Morris had transformed into the conscience of the university a decade earlier—as something resembling an administration PR sheet.

In one note found in the files, informant Economidy says, “Chief Hamilton—- Here is the list of persons which I promised you” and adds “I’ll get you the negatives of the shots I took Tuesday at the latest.” In another, he alerts the chief to two upcoming rallies and offers further help, providing his phone numbers.

Today, Economidy lives in San Antonio, where he is a criminal defense attorney specializing in military cases. Reached by telephone, he volunteered that he had provided information and photographs to Lt. Burt Gerding of the Austin Police Department—who worked closely with Chief Hamilton—as well as to the campus police. Asked if, in retrospect, he saw this as a conflict of interest with his position as editor of the Daily Texan, he said, “No doubt about it. As a journalist, it definitely was not appropriate.”

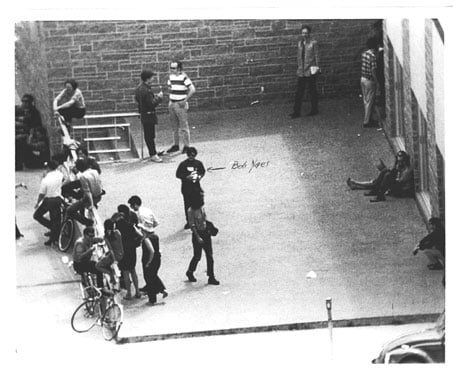

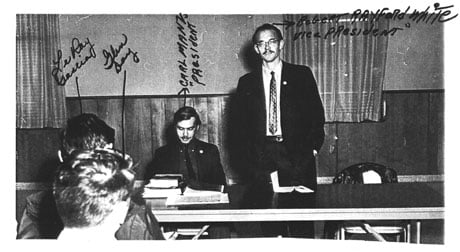

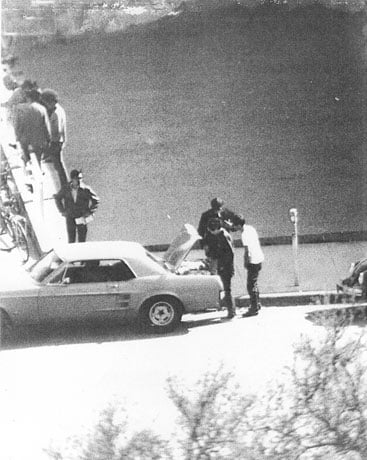

Photographs contained in the files appear to be surveillance shots of individual activists as well as antiwar and civil rights demonstrations and “happenings” like Gentle Thursday, a peaceful campus event organized by SDS. On many of the photos, names are scrawled in the margins; in others, arrows point to individuals.

The files on campus radicals include a list of over 250 names of people “associated with SDS” with addresses, phone numbers, hometowns, high schools attended, and other background information such as fathers’ names and occupations. Sometimes they include physical descriptions: Vicky Kirk is a “colored female;” Gary Chason is “growing a beard.” There is similar information on the campus Committee to End the War in Vietnam and other groups.

Highlighting the administration’s somewhat compulsive interest in students’ sexual activities, there is an entire page of background on Thomas Lee Maddux, “white male…subject is allegedly heading the Texas Student League for Responsible Sexual Freedom.” The file includes membership lists and other information about this group, an insignificant and short-lived organization.

There are clippings and notes about The Rag, a pioneering member of the underground press. They document conflicts between Rag vendors and campus police and the administration’s move to ban distribution of the underground paper on the UT campus. (The Rag sued and eventually the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the paper’s free speech rights.)

Much of the material in Chief Hamilton’s files centers on early Austin countercultural figures, musicians and literary types, especially those associated with the “Ghetto”—an old wooden Army barracks in the 2800 block of Nueces on the west side of campus that was home and/or home base to much of the hipster cognoscenti. The police also seemed focused on the activity of the staff of the Texas Ranger, the campus humor mag that incubated a number of major artistic and literary talents.

Janis Joplin numbered among those that the police associated with the Ghetto. In one entry, beside her name are scribbled the words “…suspected of bringing in amphetamines, Dexedrine, etc.” Other members of the Ghetto crowd mentioned in the files are musician Powell St. John, who would be a pioneer of the San Francisco psychedelic rock scene; cartoonist Gilbert Shelton, who was to create the iconic Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers strip that appeared in The Rag and other underground papers all over the world; and the late William Brammer, a former Observer editor whose book The Gay Place would be recognized as perhaps the finest novel about Texas politics.

Visiting poets Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti—invited for poetry readings—are cited in handwritten notes. (Ginsberg is identified as the “hippies poet.” About Ferlinghetti, they haven’t a clue.) Other names that pop up in various lists: (now U.S. Rep.) Lloyd Doggett; former Texas Observer editors Ronnie Dugger (spelled “Deuger”) and Kaye Northcott; Spencer Perskin and Kenny Parker of the classic Austin rock group Shiva’s Head Band; folklorist Tary Owens; musicians Mance Lipscomb and Jerry Jeff Walker; civil rights leader B. T. Bonner Jr.; numerous lawyers and professors; two rabbis; and Yale University Chaplain William Sloan Coffin.

As for the Ghetto group in general, the files read that they “float from place to place. Start and end at times at Gilbert Shelton’s, (or the) Unitarian Church.” In another notation: “Peyote and drugs used in wild parties on Fri and Sat night. Most of the wild crowd members of the Ranger staff.”

The files contain a photocopy of an April 18, 1963, article from the Austin American-Statesman that perfectly relates how clueless the authorities really were. The story describes a “shakedown of local beatniks” (this one by the Austin police vice squad) in which “they spotted several, spoke to a few and bagged zero.” It reports that “several girls, spotted leaving one of the apartments tagged as a beatnik hangout, scattered in all directions.” The article adds that parties were thought to be getting out of hand and informs that, according to the dean of student life, “local beats are currently getting their kicks from peyote cactus,” which, as one officer observed, “makes you dream in Technicolor.”

One document in the collection describes a female student thought to “use peyote … and other drugs, very sexually promiscuous and believed to have nymphomaniac tendencies,” and another woman is also labeled as “sexually promiscuous.”

The authorities’ apparent titillation with sex appeared to heighten when drugs were added to the mix. Yet the fascination of the police stood in stark contrast to the attitudes of these precursors of the counterculture to come. For them, sex was seen as open and natural and no big deal. But that wasn’t the only aspect of the scene that the cops got wrong.

The Ghetto is characterized on a scrap of notepaper in Hamilton’s files as “a haven for Jews.” There are several typed pages of historical analysis of the ghettos in World War II (the Austin Ghetto was in fact a nondenominational operation and was in no way related to the history of the Jewish people) and a psychoanalytical take on the Ghetto’s denizens, calling them “individuals lost in the world” with “egocentric impulsiveness,” “deviant sexual patterns,” and a “rejection of authority and discipline.” It also grumbles that they were, well, just “irritating and distressing.”

I was in Austin during this time of ferment, active with SDS and a founding editor of The Rag. My name and picture appear more than once in these files. I had friends who lived in the Ghetto, and also had friends shot by Charles Whitman. Sandra Wilson survived, as did Claire Wilson (no relation), but her unborn child did not.

So when friend and former colleague Alice Embree forwarded an e-mail from Steve Leach in the Half Price Books corporate office in Dallas offering first access to Chief Hamilton’s surveillance files, you can bet I was interested.

After discovering the files, Hamilton’s son arranged to sell them to Half Price Books, which specializes in buying and reselling used books and other printed materials. The company is itself a product of the sixties ferment, founded in a converted Dallas laundromat in 1972 by Ken Gjemre and Pat Anderson. The operation has grown to 90 outlets in 14 states, but in many ways it retains the spirit of its founders.

“Our buyers recognized that this was not an ordinary buy and that its historical value trumped any monetary value it would have as merchandise,” said Leach. “We felt that the appropriate action was to return the papers to UT.”

The owners of Half Price Books arranged to donate the files to the Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. They immediately delivered those related to the Whitman shootings but decided to hold off on delivery of the additional materials documenting surveillance of campus activists. They felt that, according to Leach, these papers had special value “as a representation of an early era in a movement that has had a great influence on politics and culture ever since.” And they worried that the papers would, in essence, be buried at the library if donated immediately.

So the management of Half Price Books decided to locate a representative of the activist movement in Austin and to provide access to the materials prior to delivering them to the university. They found Alice Embree, former SDS leader and Rag staffer. Alice contacted me and I made arrangements with Leach. We then took a crew to Dallas, where we spent several hours scanning and photocopying the entire collection. Glenn Scott of People’s History in Texas filmed the activity for a documentary being produced on the history of The Rag.

There were so many different groups that came together during that time: artists, writers, activists, musicians, motorcyclists, humorists, dope fiends, cavers, chemists—iconoclasts who came together on civil rights, the war in Vietnam, and their right to be themselves,” remembers Pepi Plowman, a part of the Ghetto crowd whose name appears in the files. “The UT cops just saw all this as a threat.”

The police used this notion of a threat to justify constant harassment, much of which involved drug busts and rumors of drug busts. Because many of those targeted were nonstudents and lived off campus, it was often the Austin police who did the dirty work. And sometimes perceived harassment was more creative: According to Clementine Hall, who was married to lyricist and jug virtuoso Tommy Hall of the legendary Thirteenth Floor Elevators, “at least twice, city fumigation trucks pulled up to the back of the Ghetto and sprayed pesticide directly on us.”

Nicholas Hopkins, who taught in the UT Anthropology Department, learned from a friend who worked in the campus police office that he was suspected of being a dope dealer because of his “frequent trips to Mexico.” His jaunts south of the border were, in fact, for academic work. “That was my area of research.” He still believes that this speculation created a cloud over him and was a factor in his not being granted tenure at the university.

The tall, balding Hamilton—who was police chief until 1970 when he went to work as a security consultant for the UT system—was called a “happy-go-lucky campus cop, friend of the athletes and pretty girls,” by Southwest Scene magazine, but the Whitman shootings are said to have had a sobering effect on his personality.

Hamilton’s campus cops worked intimately with the Austin Police Department and other agencies. In return, Lt. Burt Gerding, Austin’s “red squad” cop, coordinated closely with Chief Hamilton but, as one activist recently observed, also looked on him with a dash of condescension, viewing him as something of a greenhorn. Gerding, a wry, lanky gent with a winning style, is an Austin legend. Omnipresent, with a continually amused look and an almost “aw shucks” demeanor, he was the town’s one-man “Good Cop, Bad Cop.”

Gerding was at every meeting and event held by campus radicals, always with his ironic smile, greeting everybody by name. He loved to startle people with the information he had about them. He would offer tidbits of inside scoops or warn of impending dope raids, always implying that he was really on their side. Former campus activist Robert Pardun, author of Prairie Radical: A Journey Through the Sixties, remembers a late-night SDS group skinny-dip at Hamilton’s Pool, an historic swimming hole near Austin. “A few days later, Lt. Gerding approached (participant) Alice (Embree) and, with a wink, announced he had some real nice infrared photos of the event.”

Campus SDS leader Gary Thiher, now a philosophy professor, remembers moving into a new ground-floor apartment on Rio Grande with low windows opening onto an alley in back. “It was our first day there and we were sitting around on the floor talking when, lo and behold, we see Gerding’s face float slowly by in an unmarked police car, his face craning up so he could see into the room.” After Gerding cruised the alley twice more, Gary went outside and asked him what he was doing there. “Well, everybody has to be somewhere,” he chuckled.

Former Austin radical Scott Pittman remembers a Texas Ranger commenting to him: “Burt Gerding plays you guys like a fiddle.” When the members of the psychedelic rock band the Thirteenth Floor Elevators were busted in January 1966 for possession of marijuana, rock historian Paul Drummond recalls that band founder Tommy Hall just couldn’t believe it. “He thought Gerding would tip him off.”

Gerding, now approaching 80 and in failing health, lives in the Delwood section of east Austin. In an interview, he boasted that he always had informers in SDS and other activist groups. “If you had a meeting, I had a quorum there. They lived among you,” Gerding recalled. He looked upon us as “the enemy” because “you started the cultural revolution, and I felt strongly about my culture.”

He still blames us for the breakdown of traditional American values, but added “I don’t consider you the enemy any more.”.

One reason the campus cops and the city police were so sensitive about dissent in Austin, and collaborated so closely, may have been the political climate of the time and the desire to avoid potential embarrassments for President Lyndon Baines Johnson. “The Chairman of the UT Board of Regents, Frank Erwin, was also a honcho in the Democratic Party,” reflects Alice Embree. “I think the UT police had such a close relationship with other agencies—DPS, the FBI, the Secret Service—because of the presidential spotlight. There we were in the streets, protesting Lyndon’s war and trying to integrate the dorm where his daughter lived.”

One case that brought Austin and campus police together, but also threatened to drive them apart, was the murder of militant activist George Vizard. Respected and well liked by those who knew him, Vizard had a genuine dedication to social change and a ready sense of humor. He was also probably the most visible and volatile of Austin’s radical activists, proudly proclaiming his membership in the Communist Party. He was arrested several times and was in a number of altercations with authorities. If one were to have picked someone in the Austin left to target as an example, he would have been the likely choice.

Vizard worked at a convenience store, and it was there, in a frozen food locker, that his body was found on July 23, 1967. He had one bullet in his left bicep and another in his back. It would take 14 years for a former employee of the store, a mentally unstable campus character named Robert Zani, to be convicted of the killing.

Vizard and Chief Hamilton had a confrontational relationship, and according to Democratic political consultant Kelly Fero’s The Zani Murders, Hamilton was alleged to have threatened Vizard’s life. Initially, Austin police considered Hamilton a suspect in the case. Hamilton’s papers reveal that Robert Zani had a relationship with the police and was an informant in at least one narcotics case (information previously revealed in Fero’s book). Questions about what motivated Robert Zani to kill George Vizard linger to this day.

George’s widow, Mariann Wizard (she changed the “V” to a “W”) puts it this way: “The memo in which Chief Hamilton describes Zani’s volunteering as a narc raises the enduring question: was Zani a ‘lone nut’ or a missile aimed at the heart of Austin’s antiwar movement?”

Alice Embree called Lt. Burt Gerding’s house the morning that George Vizard’s body was found. She recalls the lieutenant saying to her, “I always told you this kind of thing was dangerous.” “Gerding may have just been rattling cages,” she says, “but [his] message was that George’s politics had put him in danger. And that that would apply to the rest of us as well.”

The spying on Austin radicals revealed in the Hamilton files was hardly isolated. Over the years we have learned the magnitude of surveillance efforts by local, state, and federal agencies—the IRS and CIA and military intelligence—against those of us involved in the antiwar activism and countercultural lifestyles of the Sixties and Seventies. And we discovered the mind-boggling work of the FBI, with its coordinated efforts not only to keep tabs on the New Left, but also to destroy it by whatever means necessary. We learned that in addition to campus radicals, the increasingly influential underground press movement became a frequent target of the authorities.

During the Sixties and Seventies, a number of government agencies had significant overlapping domestic surveillance programs. According to former military intelligence officer Christopher H. Powell, who now teaches constitutional law at Mount Holyoke College, U.S. Army Intelligence had a network of 1,500 agents dispersed throughout the country and maintained files on more than a million American citizens. The IRS was involved in “counter-subversive” intelligence operations, had massive files, and shared them with other agencies. The CIA conducted significant domestic spying, targeted SDS, SNCC, the Black Panther Party, and a number of other organizations and had a substantial campus presence with agents among the faculty and administration. Texas was no exception.

The big kid on the block, however, was the FBI, with its secret Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO). Set up in 1956, its mission was to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize.” The prime target of this activity became the New Left and the black power movement. In War at Home: Covert Action Against U.S. Activists, Brian Glick says the four main methods of operation were: infiltration; psychological warfare from the outside; harassment through the legal system; and extralegal force and violence. “They resorted to the secret and systematic use of fraud and force to sabotage constitutionally protected political activity.”

The FBI’s far-reaching program was, in many cases, extremely effective and is credited with being a substantial factor in the collapse of SDS, the underground press, and the New Left as a whole. These activities became public after the passage of the Freedom of Information Act of 1974.

In the documentary film Rebels With a Cause, former SDS national secretary Mike Spiegel recounts what he learned after obtaining his FBI files: J. Edgar Hoover had specifically instructed agents to follow him 24 hours a day and further ordered them to “promptly furnish your suggestions as to how Spiegel might be most effectively neutralized.”

“What was frightening,” said Spiegel, “was that the term neutralize could mean anything … all the way up to killing me.”

Glick points out that “close coordination with local police and prosecutors was strongly encouraged” by the FBI.

Indeed, the Hamilton files documented visits to Austin by movement activists from elsewhere in Texas and contained numerous references to national leaders such as Spiegel and Austin’s own Jeff Shero (later Jeff Shero Nightbyrd), who was a national vice president of SDS.

In the Sixties, we looked over our shoulders a lot. Even when we weren’t on drugs.

We always thought we were being watched, followed, wiretapped, photographed. We were certain that there were infiltrators and informers and provocateurs.

We just didn’t know how right we were.

Thorne Dreyer was a founder and editor of the Sixties underground newspapers The Rag and Space City! and managed Houston’s Pacifica radio station KPFT. He is a freelance writer and lives in Austin.