Izzy and All That Razzmatazz

All Governments Lie!The Life and Times ofRebel Journalist I.F. Stone

This remarkable biography/history sweeps across most of the 20th Century, a period of insane ideological and armed conflict. Any good history of the period could hardly be other than entertaining. This one is especially so since it was written by Myra MacPherson, the highly respected veteran of the Washington Post and a bevy of magazines and books.

Anyone who is even obliquely interested in the interplay of journalism and politics will be fascinated by her account of I.F. Stone’s imprint on those tainted professions. Among Washington reporters he became well known for digging through masses of government documents and finding crucial evidence of government wrong-doing that other reporters had overlooked—or hadn’t had time to look for. One can be sure that if he were still around, we would have got a much more devastatingly critical review of the bureaucratic and congressional “studies” of CIA and FBI blunders before 9/11; and of the Bush/press claims of WMD that lured us into Iraq; and of the secret surveillance of citizens in the last few years.

That being acknowledged, let me hasten to add that as a keeper of the flame at the Stone Temple, MacPherson has a charming but somewhat inflated view of her idol. Referring to a poll taken by unidentified “institutions” for her evidence, she tells us that “his tiny one-man weekly” was ranked “number 16 of the top 100 Greatest Hits of twentieth-century journalism.” I don’t know what she means by “hits” and she doesn’t name the fifteen who beat him out, but she does mention that he was “ahead of Harrison Salisbury, Dorothy Thompson, Neil Sheehan, William Shirer, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Murray Kempton, and other worthies.” That might be impressive if she hadn’t gone on to tell us that “the acerbic H.L. Mencken did not make the cut”—which should give you a handy measure for this poll’s questionable accuracy.

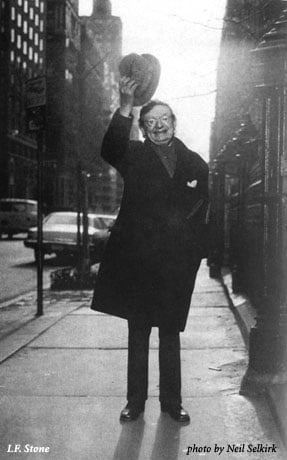

What accounts for the success that turned Stone into a minor legend? Partly, and in no small part, it was his appearance, which belied the strength of the spirit within. He was a squat little fellow who stared blandly out at the world through spectacles with Coke-bottle lenses. Since there seemed nothing about this little man to be afraid of, the shock caused by his surprising performances as an inquisitor created a kind of notoriety for him.

In a press conference or at any other encounter with government officials, he could be a terrorist with well-honed questions and comment—made all the more infuriating because they were tossed so politely, and always backed by his fabulous memory for details. On one such occasion, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles became confused and so furious that his face turned purple and he countered Stone’s question with one of his own: “What is your name?” And when he got “Stone” for an answer, hoping to dislodge Stone’s birth name, Feinstein, Welles pushed on: “Don’t you have another name?” It was such an obviously anti-Semitic trick that several newspapers editorially scolded him.

In the late 1940s, Stone was an occasional guest commentator on the radio and TV round-table Meet the Press. The Great Communist Witchhunt was already underway and because he was a well-known radical suspected of being a Communist, the show used him as a carnival might use a Borneo savage. On one occasion Stone asked Maj. Gen. Patrick Hurley, a good friend of China’s corrupt Chiang Kai-Shek, why the U.S. should go on wasting billions to prop up that fascist dictator. Hurley screamed into the microphone, “Quit following the Red line with me!” And then, just to make sure the national audience knew he was dealing with a lousy kike, Hurley shouted, “Go back to Jerusalem!”

From such encounters grew Stone’s reputation as a skilled troublemaker.

Probably MacPherson is right in calling Stone “The twentieth century’s premier independent journalist, known to everyone from the corner grocer to Einstein as Izzy.” Actually, there was little competition for that title, if by “independent” you mean a journalist who owns his own paper–be it no more than the four-page Weekly that Stone printed in Washington over two decades. As a publisher, Stone’s lucky break was the Vietnam War. The Washington Post and the New York Times both supported it editorially, but opposition to the war was so widespread and so intense, especially along the New York–Washington corridor and in West Coast liberal enclaves, that Stone’s opposition weekly, always insolently anti-war and often scholarly (he raided European papers for tough critiques), became must-reading for many, including many around the White House and Congress. It also included many on campuses across the country, where the threat of the draft hung heavy. A subscription cost only $5 a year, but the Weekly became so popular that it finally turned Stone into a millionaire.

Eugene Debs being the model, I prefer rebels who have been hard up at some time in their lives. Stone never was. At the bottom of the Great Depression, he was earning $125 a week as an editorial writer when good reporters were lucky to be paid $15 and every big city was full of unemployed men trying to sell apples on street corners.

His good luck started early. He was the pampered son (born Isador, December 24, 1907) of Bernard and Katy Feinstein. His father was a prosperous Philadelphia businessman. Pampering continued when, at the age of 15, Stone became the protégé of J. David Stern, a Philadelphia newspaper owner, and his wife. MacPherson generously acknowledges Stern’s fundamental influence on Stone’s life: “For the next fifteen years—throughout the twenties, the New Deal, the Popular Front, and Spanish Civil War, the beginning rumblings of World War II—the dynamic Stern was Izzy’s patron. He helped shape Izzy’s writing and gave him a powerful platform. Izzy became America’s chief editorial writer on a major newspaper, first with Stern’s Philadelphia Record and then with his New York Evening Post.

“The team of Stern and Feinstein, as Izzy was known through most of his tenure with the publisher [he changed Feinstein to Stone in 1938], was as stormy as it was serendipitous. In that era of Coolidge conservatism, it was a miracle that Izzy found the one major publisher compatible with his beliefs, a man dedicated to liberal, fair reporting. But that did not stop Izzy. Their parting was so bitter that Stern excised Izzy from his autobiography, Memoirs of a Maverick Publisher.”

It would be interesting to know exactly what MacPherson meant by “that did not stop Izzy.” And what she meant by Stone’s “tumultuous departure” from the Post, at that time New York’s leading liberal paper. Even to some of his admirers, Izzy was not known for being a team player, even when it was a first rate team. “Though capable of collecting friends of long standing, Stone’s pattern of ignoring colleagues angered many who felt he was a snob.” Other colleagues had other adjectives, such as “bully,” “tactless,” (which he admitted), “humorless sexist,” and “incredibly arrogant.” MacPherson says that while they continued to admire his work, “some talented and hardworking journalists and authors felt Stone, in his David-versus-Goliath mode, took cheap shots at their expense in his quest to prove his independence and their lack of it.” For the sake of full disclosure, I admit I am correctly identified by MacPherson as being among that group and am quoted as describing him as “a little shit,” while conceding that “it was hard to stay mad at Izzy” because he was “virtually always on the side of decency and fair play.”

(Shortly after moving to Washington, D.C., I worked for Stone—for three weeks, quitting after he rejected my piece that suggested Lyndon Johnson was mentally unbalanced. Stone’s reason: “Ah, we’re all a little crazy.” If I was wrong, I was in good company. In his 1988 book Remembering America, LBJ aide Richard Goodwin tells how he and Bill Moyers became so concerned in the summer of 1965 that they met every few days to discuss the “clearly visible signs of Johnson’s instability” and his “increasingly vehement and less rational outbursts.” Goodwin says they independently took their notes to two different psychiatrists” who confirmed “we were describing a textbook case of paranoid disintegration.”

Jack Raymond, a veteran New York Times reporter who considered Stone a close friend, told MacPherson, “I was amazed one day to pick up his paper [the Weekly] and find an attack on a piece of mine. For all intents and purposes he asserted that I was handmaiden of the Pentagon. I was stunned that anyone could think that of me.” Later, at a dinner party, Raymond confronted Stone, who waved away his complaint: “Ohhhhhh, Jack! Why should you care about what I write in my little paper that few people see?” Raymond says, “On hearing that, my heart sank.” MacPherson adds, “Not only had Stone ignored the larger moral question of impugning Raymond’s writing, judgment, and integrity, he attempted to get off the hook by pretending that his little rag didn’t matter. Raymond knew as well as Stone that in their circle the Weekly was a prized read.”

George Wilson, the Washington Post’s Pentagon correspondent who broke numerous tough stories in the 1960s, told MacPherson, “Izzy would give me credit [in his Weekly]—and then he would put his own spin on it. He would say, ‘Wilson said this … and this is what I think it means.’ Which was all right—but just don’t call him a reporter. There was only one side of the story for Izzy. He called once and said, ‘There’s so much I don’t understand about the strategic missile race and you understand it and I would appreciate having lunch.’ At lunch it became apparent that he really didn’t want to learn anything. He just wanted to deliver a diatribe on the badness of the arms race … . I had to take Izzy in small doses.”

With the end of the 1930s and his departure from Stern’s nest, Stone’s soaring career had crashed and his future looked bleak. But in 1940 the radical Nation magazine made him its national Washington correspondent, and that good luck was followed by even better luck: a job on PM, launched by Ralph Ingersoll, “a wealthy, neurotic, flamboyant genius … who couldn’t make a move without consulting his psychoanalyst.” It was a newspaper made by and for the young at heart. Ingersoll was 39, Stone was 32.

From the first day, writes MacPherson, it became “the most daring newspaper experiment of the twentieth century. PM was a tabloid that refused to pander: there were no racing sheets, no stock market reports, no pictures of stripteasers being hauled off to jail. But his major revolution stunned the publishing world: Ingersoll was going to try to make money or at least break even with no advertising.

“PM often scored in crusades that mainstream, corporate-friendly newspapers largely ignored. It exposed the practice of the American Red Cross to segregate blood, deeming that the blood from black donors could not be used for white soldiers. Remarkable for its time, PM attacked segregation and lynchings like no other newspaper catering to white audiences.

“In the first year and a half, PM exposed the Standard Oil Company, the Aluminum Trust, life insurance scams. It dogged Charles A. Lindbergh’s romance with Nazi Germany and isolationist William Randolph Hearst. It took on Father Coughlin and the powerful Catholic Church. Freed from advertisers, it passionately supported unions and workers’ rights, including the right to strike during wartime.”

PM was, obviously, a perfect place for Stone, and he shone as one of Ingersoll’s (and the Nation’s, where he was also writing) brightest investigative reporters and columnists. Among other things, on the eve of World War II, his stories forced U.S. oil giants to stop shipping oil to Hitler’s Germany by way of Franco’s Spain. Some of his later exposes forced the government to radically improve their wartime production lines. And another of his series revealed the Civil Service Commission was victimizing government workers who were suspected of liberal beliefs—”the Red Scare was already in full swing.”

The splendor of PM‘s differences at first set New York agog. “More than ten thousand reporters applied for the two hundred available jobs.” Ingersoll, being Ingersoll, at first hired only friends who were famous or on their way to fame—the likes of James Thurber, Dorothy Parker, Ben Hecht and Lillian Hellman—but some had never been inside a news room.

Naturally, there was chaos. And, up to a point, the staff thrived on it. So did the paper, up to a point. As MacPherson tells it, “PM‘s irreverent nose-thumbing enraged hard-line reactionaries and racists, much to the delight of its staff, especially the paper’s treatment of the avowed leading racist and anti-Semite on Capitol Hill, Congressman John Rankin.” The paper always spelled his name in lower case.

The paper had an absolutely devoted following. But not among working class readers. They missed the ads. And the missing ads meant suicidal loss of revenue. PM died. A.J. Leibling, the New Yorker’s friendly critic, noted, “One of the good things about PM was that it was different from any other New York paper, and the differences were irreconcilable. Also, it was pure of heart. The injustices it whacked away at were genuine enough, but an awful lot of whacks seemed to fall on the same injustices. A girl to whom I gave a subscription to PM in 1946 asked me after a time, ‘Doesn’t anybody have any trouble except the Jews and the colored people?'”

Anyone fascinated by the history of offbeat—way offbeat—journalism will be exceedingly grateful for MacPherson’s all-too-brief tour of PM, a tour that will make Texas Observer readers grateful that at least some of PM‘s razzmatazz spirit still surfaces in the stuff of, say, Hightower and Ivins. Indeed, if readers believe in transmigration, they might even think that in the impudent judgments of Hightower and Ivins they hear the voice of I.F. Stone. The title of this book comes from one of his written comments, “All governments lie, but disaster lies in wait for countries whose officials smoke the same hashish they give out.”

He had been lacing his editorials with such comments for years, and they would become more commonplace in his Weekly. Its survival was something of a miracle, considering that its left-wing audience was split into so m

ny civil-warring

factions. It had been thus since the 1930s, writes MacPherson, when “Only an optimist like Stone could have hoped for a united left … . Communist Party members were venomous to the socialists, old-guard socialists were battling with new-guard socialists, mutant strains of Marxists were battling one another.” It was still going on when the Weekly was founded. One guess as to why Stone not only survived but thrived is that it was hard to tell exactly where he fitted in the Left.

He couldn’t have been more militant in his defense of civil liberties, but he wrote not a word in protest of the mass incarceration of West Coast Japanese, many of them U.S. citizens, at the start of World War II.

More than anything else, he was a pacifist. He hated President Truman’s militarism—the “doctrine” he scared Congress into passing in 1947, leading to global confrontation with Communists, promptly in Korea (a war in which 50,000 U.S. servicemen died)—and Truman’s phony “loyalty program,” which purged large numbers of federal employees and set the stage for the nihilistic anticommunist crusade of Joe McCarthy. Indeed, Stone hated Truman so much he supported Henry Wallace in 1948, even though he considered Wallace “a cross between a saint and a village idiot.”

Stone’s pacifism made him too eager to believe the best of Stalin. In 1939 the Nation printed Sidney Hook’s “manifesto against totalitarian regimes,” lumping Stalin with Hitler and Mussolini. Stone wrote an angry rebuttal, for which he got 400 cosigners, in which he praised the Soviet Union as “a bulwark against war and aggression, and for working unceasingly for a peaceful international order.” It said Stalin’s Russia “has eliminated racial and national prejudices … and made the expression of anti-Semitism or any racial animosity a criminal offence.” (Actually, up to that time, Stalin had probably killed more Jews than Hitler had.) Stone’s rebuttal assured Nation readers that “The Soviet Union considers political dictatorships a transitional form …. There exists a sound and permanent basis in mutual idealistic cooperation between the USA and USSR in behalf of world peace.”

Stone’s manifesto appeared in the Nation on August 10. Thirteen days later Stalin and Hitler signed a non-aggression pact, forging an alliance that made World War II a certainty. A week after the signing, Germany invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war.

Stone was furious at being proved such a sucker, but he credited Russia with saving American lives during World War II and for a time after the war he refused to believe all the stories about Soviet slave camps and mass executions. By 1948 he was saying the Russian government “depended on outlawry, suppression and terror.” And after Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 litany of Stalin’s horrors, Stone vociferously criticized Russian Communism for the rest of his life.

But what he had to say about Russia after that was not much harsher than what he had to say about the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which in 1952 he accused of trying to set up “an American police state.”

Was Stone a Communist, or had he ever been? Nobody knows. He denied it, while admitting, very late in his life, that he had been a “fellow traveler.” He had once openly suggested that the ideal political philosophy would be a blend of Marxism and Jefferson. To J. Edgar Hoover, that sounded subversive enough. By the end of Stone’s life, the FBI had amassed 5,000 pages on him.

The only truly irritating and sloppy reporting I found in All Governments Lie was in Stone’s handling of his trip into the Deep South during the Little Rock school crisis. Or perhaps MacPherson’s re-reporting of Stone’s trip is at fault. In any event, they make it sound like all Southerners were segregationists. Lord knows there weren’t lots of exceptions, but the story would have been fairer if they had not ignored some evidence of sanity, which Stone surely must have known about.

On his way to Little Rock in 1957 after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the high school in that city to integrate, Stone stopped off in Nashville. “Reading the Nashville Banner,” we are told, “Stone saw an editorial cartoon that was a far cry from the fiery creations of the Washington Post’s Herblock. ‘Education Be Hanged!’ said the caption, with a grotesque caricature of Chief Justice Warren.” Okay, but the Banner was a notoriously right-wing newspaper. Why not tell us the response of the first-rate newspaper next door, the Tennessean, on whose staff were such world-class reporters as David Halberstam, who would later win a Pulitzer for exposing our military stupidities in Vietnam, and John Seigenthaler.

(Seigenthaler later became Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s chief of staff. When one of the Freedom Riders buses reached Montgomery in 1961, a mob of white men armed with clubs and bricks attacked the riders. Seigenthaler came to the rescue of an elderly female black, throwing his body over hers, and was promptly knocked unconscious, winding up in the hospital. Some segregationist!)

And we are told that “Since the media were covering the Little Rock story ‘almost entirely from the white side,’ Stone went to the dingy quarters of Little Rock’s Harlem” to get the truth. As a matter of fact, the Arkansas Gazette had opposed Governor Faubus and supported the Supreme Court’s integration order from the outset, and didn’t back up an inch when Faubus and the powerful Citizens’ Council organized a boycott that cost the Gazette millions of dollars. Oh well. You know how those Yankee reporters are.

Robert Sherrill is a longtime Observer contributing writer.