This American Life

Translation Nation: Defining a New American Identity in the Spanish-speaking United States

Mexican New York:

On a road trip through the Midwest boonies in the early 1990s, I was astonished to see signs plastered in Liberal, Kansas, advertising a local concert by the Mexican pop band Los Bukis. Though the Bukis had been performing in Chicago for over a decade, that was to be expected, since Chicago was an immigration magnet even by the ’70s. But the band’s tour to cornfield, white-bread Liberal was new: evidence that Mexicans were seeping into the tiniest crannies of the U.S. Back then the realization felt esoteric. Now it’s common knowledge. And for many, common panic.

The rational response to any social hysteria is to marshal calmative facts. “Only 57 children are kidnapped and killed by strangers each year—not 50,000.” “Public health statistics show that marijuana is not a ‘gateway’ to heroin.” “Homicide rates for women in the U.S. do not rise on Super Bowl Sunday.” Likewise, one response to Sensenbrenneresque ranting is to cite data showing that immigrants do not harm the economy, are not linked with high crime rates, and so on with an endless counting of beans (or in this case, perhaps, frijoles).

Beans can help, but anti-immigrant feeling is generally less about fact than about symbol and political expediency. In the long run, number-crunching never cures hysteria. Freud treated it by having sufferers tell the story of their lives: turning wooly experience into a genre of literature, the clinical tale. He doubted such stories would produce joy. Only—as he put it—”ordinary unhappiness,” but that was enough. As another genius of letters implied, every happy person is the same, but each unhappy person is unhappy in her own way. The differences are what make life uniquely livable.

Literary-grade narratives of the neo-immigrant experience will not stop hysteria either, but they’re not obliged to. It’s sufficient for them to just be, in all their wooliness and ordinary unhappiness, evoking the immigration status of the reader’s soul, whether that soul has been here—hopeful, striving, and neurotic as hell—for just a few years or as long as the Cherokee.

Héctor Tobar’s work feels like that. As a reporter for the Los Angeles Times (currently as Mexico City bureau chief), he’s certainly fluent with facts. But he’s also a novelist. As well, he’s the son of Guatemalan immigrants and grew up in Los Angeles, where to be Guatemalan is to be a Chicano. Or Hispanic, Latino, whatever. In the family’s neighborhood in Hollywood, Tobar’s mom styled her hair in a beehive. His dad wore argyle sweaters, studied business English obsessively, and lionized Che Guevara. He told little Héctor that Che was a heroic guerrilla, and to Héctor that meant traveling from Argentina to Cuba to Bolivia by swinging through trees. Big Héctor now knows what guerrillas are, and he understands that Che worship (including, once, a discussion about how nice it would be to hijack a plane to Cuba) was his U.S.-naturalized and U.S.-angsted father’s way of proving “he had not become a total gringo.”

Tobar takes as given that Latinos like his parents are in all the crannies now and that many still cherish security-blanket icons that might seem foreign to the U.S., even hostile. But—on the surface, at least—Tobar feels no need to justify these immigrants’ presence here to people who have doubts. Instead, he tells complex, existential tales: mostly about the immigrants, but also about gringos who seek redemption by expelling newcomers, and those who pursue it by running welcome wagons. The stories he recounts are at once timely, humble, bittersweet, and timeless. They’re much like Sholem Aleichem’s work about an earlier immigrant wave, except they’re not fiction, they’re reporting—sometimes even investigative reporting.

In one chapter, Tobar dresses down, goes to McAllen, and signs up with a labor recruiter there to work at a Tyson Foods Inc. chicken-butchering plant in Ashland, Alabama. For three days he rides a bus with people like middle-aged Gregorio, 19-year-old Linda, and Linda’s husband Frankie. Gregorio, a former goat herder from deep in Coahuila, is arthritic and can’t quite figure out why he keeps chasing minimum-wage work in the United States when he could just as well retire in Mexico. Tobar thinks it has to do with proving manhood, and with the seductions of the open but dark U.S. road. Gregorio is using immigration to make of himself a Ulysses. Linda and Frankie, meanwhile, are on the lam from Frankie’s rep as a gangbanger in Crystal City. Alabama means new beginnings, complete with a Bible and the loving ministrations of Mr. Bob, pastor of the local Church of Christ. Everybody lives in a crappy rural trailer park, where the only thing to do is commute to the Piggly Wiggly or to a rumbling, slippery, chicken-o-cidal job that “erases portions of your memory if you do it too long.” Latinos have signed on for the erasure, thereby transforming Dixie’s demography and, eventually, the region’s own memory.

Elsewhere in Translation Nation, Tobar profiles Agent Scott Marvin, of the “new,” “better-trained,” “better educated” Border Patrol. Marvin has been to grad school; he says things like, “At night the lights of Tijuana shine like jewels, and the lights of San Diego are equally radiant.” He also proudly points out the Border Patrol’s ground sensors and thermal-imaging equipment—hi-tech jewels that force would-be immigrants back to Mexico or to detours through the Arizona desert and perhaps to their death. And Tobar presents Benjamin Reed, who DJs an afternoon radio show in Rupert, Idaho, catering to Mexican immigrants. Reed starts his program with a recording of accordion music and goats braying. Though he’s an Idaho native with no Latino heritage, he has developed an idiomatic fluency in Spanish and calls the language un alivio—a relief, “the lifting of a burden.” (Tobar fails to mention that CNN’s Lou Dobbs, who engages in nightly anti-immigrant tirades, was raised in Rupert, though he now lives in New Jersey. Does he ever go home to visit kin? Does he secretly spin his radio dial there to Estación la Fantástica?)

Tobar is also interested in a burden that Latino immigrants themselves are slowly laying down: the weight of their longstanding civic apathy in the United States. Low voter turnout even among naturalized citizens, grotesque bossism, and corruption in communities whose politicos are fellow ethnics—such is the legacy of caciquismo in the old countries, combined with fear, humiliation, and grinding overwork in the new one. Translation Nation came out months before the mega-demonstrations this past spring, in which immigrants filled the streets in big cities and the tiniest burgs, demanding a sympathetic national immigration policy and chanting slogans about how they’re here and they’re staying no matter what. Are these protests a harbinger of new political energy—not just for Latinos but for the body politic in general?

The answer is tough to predict. Back in the crannies, though, Tobar found tenacious and heroic democrats like Carmen Avalos, of South Gate, California. Her town was run by a Latino political strongman who stayed in power by having his foes’ homes firebombed, or their heads pierced by bullets. Avalos was a high school biology teacher who decided on a spur of the moment to help clean things up. With no knowledge of how to run for office, she did so anyway and managed to get elected city clerk—meaning she would supervise elections in South Gate. During the campaign a disemboweled teddy bear appeared on her lawn; after she won, the town administration wouldn’t tell her where her inauguration was to take place, and later they tried to recall her from office. Avalos persisted, eventually overseeing an election that kicked out the strongman. She attributes her strength to her father, a former peasant from Mexico with a second-grade education and 19 siblings. One died in infancy of malnutrition and had to be buried by Avalos’ father—then seven years old—in a cookie box.

“Hunger knocks me down, but pride picks me up,” her father used to tell Avalos in Spanish. Tobar doesn’t say so directly, but he focuses on hunger for pride as a motive force that pushes immigrants to civic-mindedness. He loves to quote Alexis de Tocqueville, who concluded in the 1830s that participation in local politics was what defined Americans: “The New Englander is attached to his township not so much because he was born into it, but because it is a free and strong community, of which he is a member, and which deserves the care spent in managing.” Many Latino immigrants import from their home countries a proud legacy of participation in unionism and revolution; once here, they inject that experience into U.S. politics. Others come with nothing. But this nation will translate them into citizens, just as they will translate everyone else into Pan-Americans. That’s the deeper political vision beneath Tobar’s storytelling. It undergirds the ordinary but fascinating unhappinesses of the characters in his book. And in the end it reassures all those panicky gringos who keep counting beans.

Robert Smith’s work is quite different. He’s a sociologist dealing with New York City, a place far trickier—neurotic?—than the country as a whole. Nothing in New York is easy, not even Mexicans. Smith spent over a decade doing fieldwork among people who hail from a small municipality in the state of Puebla, which he pseudonymously calls Ticuani. People from there started coming north in the 1960s, and migration speeded up after pioneers got amnesty under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, then sent for their families.

Today, half the municipality’s population is still on its sleepy pueblo turf. The other half is in the United States, mainly in la capital del mundo. Immigrant Ticuanenses live in the five boroughs, but the boroughs might as well be countries: Brooklynites won’t visit friends and relatives in Manhattan or Queens, and vice versa, because the subway commute feels—as a teenager named Linda puts it—”mad far.” Yet come December, people sojourn thousands of miles back to Ticuani to reunite for the traditional, seasonal fiesta. During the rest of the year, they collect money in New York to support infrastructure projects in the hometown. They also send kids who misbehave in New York back to Ticuani to be rehabbed by an imagined simpler life. Smith looks at these activities and the effects they have on Ticuanenses who have settled here.

Discussing “transnationalism” these days, the fashion is to celebrate how immigrants’ links to their native communities enrich both the old country and the new one. Hooray for all those soccer teams in Dallas that are named after towns south of the border! Let’s give it up for the hundreds of mutual-aid groups that send funds home, building schools and clinics so the folks left behind can stay put! This is more feel-good neo-Tocquevillism. But as Smith shows, things are more complicated, and cheerleading doesn’t explain much.

One of the most fascinating things about Mexican New York is its sensitivity to matters of gender. Traditional, rural Mexican Catholicism fosters a partriarchy whose repressive practices against females can be compared in their severity to the mores of the Taliban. Many young Mexican women who’ve moved to the United States talk about how happy they are to be out from under the macho thumb of the rancho. Men also often change their ways when they come here. They learn not only that both parents must get jobs and share housework, but that much employment for immigrant men is in food service—complete with aprons and stints at the stove. Despite these role changes, young women whom Smith interviews in New York complain that their parents let their brothers leave the house, but not them. The macho ideal of cloistering daughters survives among Ticuanenses in the U.S., where the adolescents have a distinctly urban and English word for the practice: “lockdown.” In New York City, where public life can be the most liberating life in the world, many Mexican girls are kept in a spiritual Rikers.

On annual visits to Ticuani, though, parents let daughters walk the streets, attend parties with other kids, and stay out late. The United States is a prison; Mexico is freedom. Freedom with a price: They’re only allowed to roam because male kin also undergo a transformation on the trip from New York to Ticuani. Brothers and boy cousins assume the job of “keeping an eye” on the girls—which, of course, returns men to their traditional roles. Conflicts arise, fights break out. And because old machismo and its new insecurities underlie the dynamic, things can get violent enough to cause injury and death.

Meanwhile, back in New York, gender troubles are exacerbated by racial and ethnic tensions that are rarely talked about, but which Smith has the courage to coolly dissect. “Latino” is a cheerful, “transnational” expression, and so, perhaps, is “people of color.” But in New York, some groups of Latinos and people of color have it in for others. Young Puerto Rican men often beat up, rob, and insult Mexicans, as do African-Americans. On the other hand, some white ethnic groups have high rates of recent immigration and skins dark enough to make them sympathize with people from places like Ticuani. Italians in New York don’t mind a few Mexicans in their midst, and Greeks give them jobs in restaurants that often allow advancement. Mexicans who live in mainly Italian neighborhoods may settle into a comfortable sense of assimilation to mainstream U.S. culture.

But in neighborhoods where Puerto Ricans predominate, young-man macho posturing often resurfaces as a defensive response to harassment. In New York, however, the machos don’t look or act like ranchero singer Vicente Fernández. Instead, they obsess about not wanting to be seen as putos—”faggots,” as they translate it to English for Smith and his assistants—and they form gangs. For models they use Hollywood films such as American Me and Blood In, Blood Out. They can end up wreaking mayhem, and when parents send them to sweet, picturesque Ticuani to straighten out, they start gangs there, too.

Indeed, all is not so great in Ticuani, even with the new well, potable water system, and rehabbed church—all paid for by native sons and daughters in New York. Almost two-thirds of Ticuani households depend on remittances from relatives in the United States. Countless other towns in Mexico survive the s

me way: Today, dollars sent by kin living outside

f the country are one of Mexico’s biggest sources of foreign earnings. But as Smith explains, a remittance economy “dollarizes” Mexican communities, inflating prices that residents pay for goods. The dollars create a “remittance bourgeoisie” who live comfortably, and a “transnational underclass, who receive no remittances.” As a result, the poor in places like Ticuani can’t afford to take on the faina—the centuries-old, traditional obligation of contributing to projects like building a well. The task is assumed by people north of the border, removing an important piece of local civitas from the very people who remain in the locale. And poor young men who have stayed in the pueblos become especially vulnerable to the lure of north-of-the-border culture—including the transnational gangs that now make even Ticuani’s streets risky.

It all sounds depressing, but for Smith it’s not the whole story. Ticuenses’ ties to their pueblo create some problems, but help tremendously with others. Héctor Tobar found people like Rev. Bob and the gringo DJ welcoming Mexican newcomers, but everyone knows that such hospitality is exceptional. Most undocumented immigrants live in constant worry of being chased down by the authorities and deported. More and more, the state tells them no: no medical care, no drivers’ licenses, no college for the kids. And most important, no ballots—even for noncitizens who are documented. Without a sense of franchise, Mexicans have little motivation to assimilate, integrate, or whatever they’re supposed to do now that the melting pot is passé. Ties to places like Ticuani at least give them a sense of belonging, a sense of being in Tocqueville’s “free and strong community… which deserves the care spent in managing.”

This country is eager to administer newcomers’ labor. But until the newcomers are allowed to help administer the U.S., running bits of Mexico from a world away will somehow have to do. The situation is depressing, yet so everyday during these strange, imperial days as to seem quite commonplace. Still, ordinary unhappiness is always uniquely interesting. And Smith does a great job with the details, not just counting the beans of immigration, but spilling them as well.

Contributing writer Debbie Nathan is the author of Women and Other Aliens: Essays from the U.S.-Mexico Border. She lives in New York City.

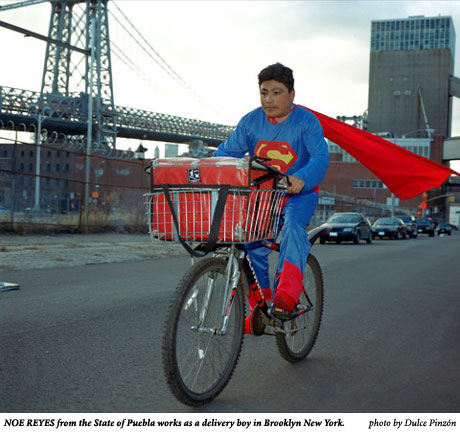

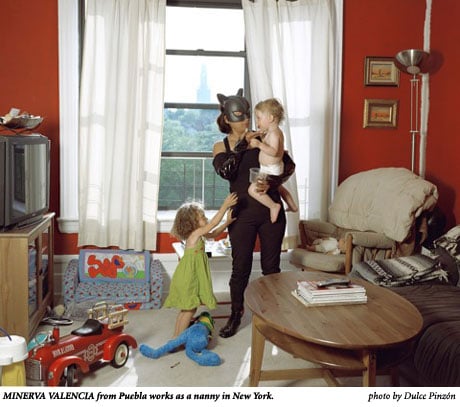

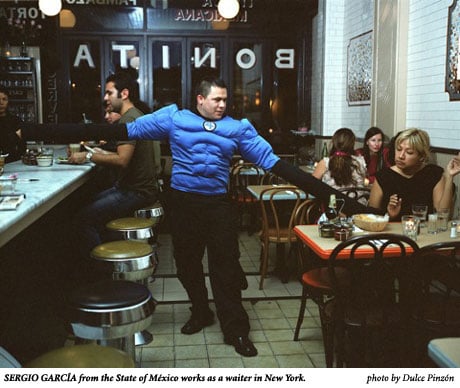

Photographer Dulce Pinzón was born in Mexico and now lives in Brooklyn. The photographs in this article are from a series called “Superheroes.”