Eating Mexican Food on Texas Avenue

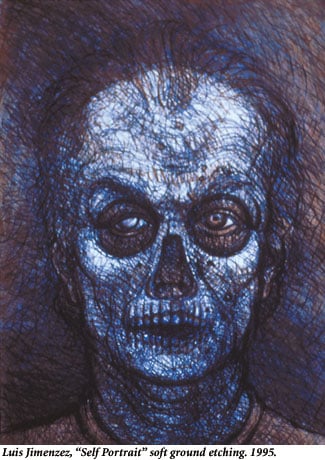

Artist and sculptor Luis Jimenez is dead. The angels killed him. They had been pestering him for years. When he was a kid, walking in the alleys, he was shot in the eye with a BB gun. In 1965 the angels cracked up his car and sent him to the hospital with a broken back. In the 1990s, in pure malice, they plucked out his left eye, the one injured by the BB. They clawed at his right arm and hand—enough that he needed operations. Twice they packed him off to the hospital with heart attacks. But he kept working; his art kept him going. He was a blue-collar workingman. He loved his tools. He wore a big, complicated utility knife on his belt and had a nice big pickup.

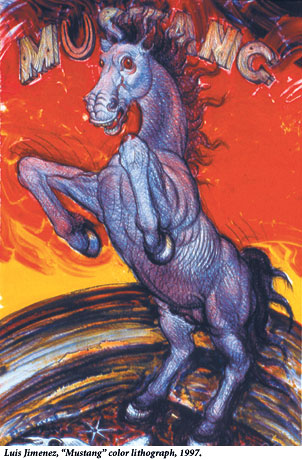

Houston sculptor Sharon Kopriva says Luis was the hardest-working artist she has ever known. He wouldn’t leave it alone. And he was happy when he was lost in his work, his art, using his hands—the stupid angels had left him one eye in his head, and he saw things only a fronterizo could see. Inside that peculiar geography, strange things happened—sex and death danced with the drunks and vatos; cowboys and Indians rejoiced in their legends and defied the onslaught of Manifest Destiny; automobiles made love to America; the myths of Mexico wandered the streets on the sides of low-riders and mingled with the pedestrians of Albuquerque. So he kept on working in the midst of a horrendous divorce and the battles with lawyers. The city of Denver was after him about the “Blue Mustang”—the sculpture that was supposed to have been installed at the airport years ago. The Blue Mustang was cursed.

And of course the angels chose the Blue Mustang with the beautiful eyes of fire as their murder weapon. Thirty-two feet of steel-supported fiberglass and years of labor. Luis was atop a ladder, hoisting a piece into place, and the angels pushed the Blue Mustang down on top of him.

When I was young, I felt my skill was inherent in being Chicano, inherent in being Mexican, and that every Mexican not only had ability but appreciated art. It was a kind of fantasy, but certainly within the context a positive thing.

The art of Luis Jimenez was rooted in the gritty aesthetics of El Paso—the rasquache aesthetics that grow out of the bones and dirt of the desert, an aesthetics that speaks poor Mexican and broken English so that it can somehow endure the relentless expectations of America. He worked in his father’s Electric Neon shop and helped design some of the bizarre neon signs that still are sprinkled around the city. He traveled through Mexico and saw the work—sketches, paintings, and murals of Rivera, Siquieros and Orozco. They were sometimes funny, political, violent, and populist. The murals especially—heroic and monumental. And in the late 1960s he strode into the belly of the beast, New York City, awash with Andy Warhol-Marilyn Monroe pop culture and intellectual minimalism. The New York art world disdained American regionalism and didn’t know what “Chicano” meant. Still, Luis paid close attention and learned what he wanted to learn. He began to make waves, but he never forgot where he came from.

Sometime in the 1980s I was in downtown El Paso, wandering through City Hall in search of some bureaucratic permit to fix my house. I turned a corner and there on the first floor, bigger than life, stood Luis’s huge “Border Crossing,” a Mexican man with bandana wading the Rio Grande with a woman in a shawl on his shoulders. The woman was carrying a child in her arms. The family, pura indigena, was immigrating illegally into the United States. They obviously had their own laws to attend to—life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. The piece was 12 feet tall, made of the polished fiberglass that made the form seep with deep fluid color. In the guise of art, Luis had infiltrated City Hall with contraband ideology.

The piece was on loan, so it disappeared after a few months. I know because I went looking for it. It had become part of my imagination. Years later I saw “Border Crossing” standing in the December snow near the plaza in Santa Fe. The hoity-toity walked by, and nobody paid attention. I daydreamed about stealing the sculpture some drunken night and bringing it home to El Paso. I would install it on the El Paso Street Bridge. It belonged in the ferocious Chihuahua sun.

I had wanted to make a piece that was dealing with the issue of the illegal alien. People talked about the aliens as if they had landed from outer space, as if they weren’t really people. I wanted to put a face on them; I wanted to humanize them. I also wanted to deal with the whole idea of family … I went back to my experience in El Paso where this is a common sight. … It was dedicated to my dad, at which point my dad said, “You know, I was never an illegal alien. I just never had my papers straight.”

When his mother was alive, Luis would come to El Paso often, and he’d stop by and visit. We’d walk down to the Mexican Cottage on Texas Avenue. Luis usually got the caldo de res, and I got the chile relleno plate with the beans and rice, although I know it’s impossible to be a good vegetarian on Texas Avenue. There used to be a waitress there, a woman in her 30s, who would flirt with us. She’d call us los guapos and los reyes de la avenida—both of us gray-haired 60-somethings, Luis with the one eye and me with the bald head and the goofy hat. We’d laugh with her and do some flirting of our own. Luis especially got a kick out of playing with the coy side of Spanish and explaining to me, his gabacho friend, what he was saying. The waitress would bring us special gifts from the kitchen.

The last time Luis visited, his mother only had a few days remaining in her life, and Luis told me about sitting with her as she labored with her breathing. She knew she was dying. He’d try talking to her, but she’d slip away into sleep. He pulled out his sketchbook and sketched his mother as she lay dying. His sister walked in while he was sketching and got mad at him. Here their mother was dying, and all he could think about was making art. Luis was hurt by his sister’s anger, but he understood. All his life, he said, his art got between him and the people he loved. “But,” he said in an almost plaintive voice, “that’s what I do. I make art. That’s how I understand.”

Making art cut through the crap. The confusion slipped away, and all that remained was the man working.

The waitress at the Mexican Cottage has disappeared. I never even knew her name. The new waitress is nice, but she’s slow and almost as old as I am. And Luis is dead. That goddamned Blue Mustang. He bled to death on his studio floor.

We’ll miss him, huh?

Luis Jimenez was born in El Paso on July 30, 1940. He died on June 13, after a piece of sculpture fell on him in his studio in Hondo, New Mexico. Bobby Byrd’s new book of poems—White Panties, Dead Friends and Other Bits & Pieces of Love—will be available in August.