Dateline

In the Wake of Rita

In late November, two months after Hurricane Rita, outward signs of recovery in Port Arthur were in abundance. Many businesses had reopened and put “help wanted” notices in their windows; traffic signals were gradually coming back online; and every functioning hotel in town was filled with contractors engaged in rebuilding the city. Although damaged homes and businesses were legion, Port Arthur clearly had avoided the widespread flooding Louisiana and Mississippi suffered under Katrina.

But while the citizens of Southeast Texas offer thanks that nature spared them extreme devastation, their relative good fortune has a drawback: They are forgotten. In more than a dozen interviews with citizens and officials in this impoverished waterside town, the sentiment that Port Arthur is still largely on its own cut across lines of race and class. “You get on the phone with [government coordinators for hurricane relief] and it’s New Orleans, New Orleans, New Orleans,” said Hilton Kelley, the founder of Community In-Power and Development Association, a nonprofit community organization focused on underdevelopment and environmental racism in the Port Arthur area. “I say, don’t forget about Texas. We’re living in the shadows of Katrina.”

Deputy Chief of Police John Owens echoed Kelley. “You hear absolutely nothing about Rita,” he said, while watching a Fox News report on New Orleans in his office. “The only thing we can come up with is we don’t have enough chaos or citizen outrage.”

But for those struggling with day-to-day survival, a devastating storm is like a kick when you’re already down. For many in the black community in Port Arthur, the weeks and months after Rita have been fraught with uncertainty and further confirmation that they are forever on their own. Being poor and black in Port Arthur (blacks make up more than 43 percent of the population) already means dealing with formidable obstacles: an unemployment rate that historically averages 13 percent; health effects from pollution-spewing petrochemical facilities that neighbor the low-income parts of the city; troubled relations between the minority community and the local police; and a general air of malaise and apathy among the citizenry that plagues any local activist who wants to change the status quo. These problems are, of course, not unique to Port Arthur. But where Katrina quickly made New Orleans into a case study on the ills of poverty in America, here in Texas, Rita exacerbated and buried Port Arthur’s troubles.

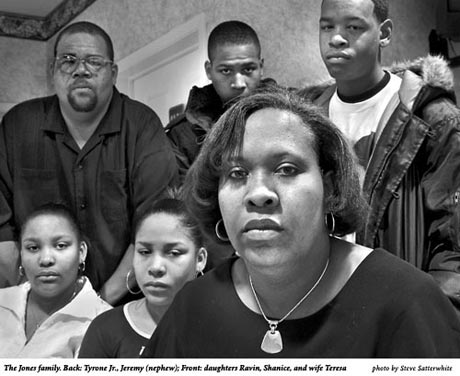

In Port Arthur, it’s sometimes difficult to separate the pre-existing dilapidation from the hurricane’s damage. Downtown looks like a war zone—acres of empty lots where thriving homes and businesses once stood, crumbling multi-story buildings, and streets empty of people except for a few men aimlessly standing on street corners. Just west of downtown lies the Westside, home to housing projects and a set of busy railroad tracks that demarcate the part of town where black residents were forced to move in 1911 as part of the city’s segregation policy. Here, blue tarps—marking damage from the storm—still dot the roofs of shotgun shacks. Curbs are lined with neat mounds of debris and toppled trees punctuate the occasional yard. Just down the street from a muddy lot littered with rusting carnival rides and a few blocks from the entrance to the 3,500-acre Motiva refinery is the home of John and Gloria Jones. The elderly couple showed me the program from the funeral of their 36-year-old son, Tyrone Jones, who died on October 13, the day of his mother’s 74th birthday. The program is circumspect about the cause of Tyrone’s death, but the family is not. “They wrongfully killed my brother,” said John Edward Jones, Tyrone’s older brother. “They” would be the Port Arthur police officers who repeatedly used a Taser on Jones, causing his death, the family believes.

The stage for Jones’ death may have been set on September 21, when martial law went into effect in Port Arthur and the surrounding area in anticipation of Hurricane Rita. The same day, city officials announced a mandatory evacuation order and a nighttime curfew. The curfew wasn’t enforced until the day after the hurricane made landfall and was lifted on October 10, according to Deputy Chief John Owens. He credits the absence of storm-related fatalities and minimal looting to the mandatory evacuation and the intensive police presence. He estimates that 75 percent of residents left before the storm hit, keeping many would-be looters off the streets and potential victims out of harm’s way. “During the evacuation, [Port Arthur] didn’t have a single fatality,” said Owens. Equipped with SWAT gear, including M-16 rifles, the Port Arthur police re-entered the city in force the day after the storm cleared. “We saturated the city with police personnel,” said Owens. The PAPD set up a law enforcement command center at the Holiday Inn in coordination with city officials and the county judge, as well as personnel from the FBI, DEA, ATF, Coast Guard, and the National Guard. The Houston Police Department “sent at least 26 officers per day to Port Arthur for 17 days,” beginning on September 30, according to a statement made by the Houston Chief of Police. HPD officers worked rotating 12-hour shifts alongside the Port Arthur cops.

Even as residents poured back into town in the days and weeks following Rita, the martial law atmosphere prevailed. Tyrone Jones may well have been a casualty of the police’s siege mentality. “The citizen was the enemy. It was feedback from Katrina or just wariness—for whatever reason,” said one eyewitness to the Jones incident. The eyewitness, an imposing man in his mid-forties with a shaved head, asked not to be named because he fears police retaliation. His account, coupled with a description of a 30-second police video, that captured some of the incident?which at press time is still not public?are the only public information available on the incident.

The Jones killing took place at the Port Arthur Town Homes, a modern and attractive low-income housing complex that seems to have been a focal point for post-Rita problems. What occurred the night of October 13 in the nearly empty complex is currently the focus of a grand jury investigation. The eyewitness was barbecuing outside his girlfriend’s apartment, several doors down from Jones’ apartment. At approximately 9:30 p.m., Jones came into the parking lot outside his apartment. Immediately, the eyewitness noticed that something was not right. “The dude, if he ain’t crazy, he planted to the teeth. He took all his clothes off; he out of his mind.” He approached Jones to see if he was going to make trouble. Jones ignored him. “That let me know right there he didn’t want any confrontation with us,” he said.

Members of Jones’ family are unsure why Tyrone was acting bizarrely that night. Both Tyrone’s brother and sister had seen him just a few hours before his run-in with the cops and report that he was acting normal and sober. (They describe Tyrone as a “jokester” and “happy-go-lucky,” a man with a wife and kids who was not a drug abuser and held down a steady job with a construction company. Jones’ wife, however, does recall one time when Tyrone had a mental breakdown.)

A neighbor called the police, who arrived around 10 p.m. According to the eyewitness, the first patrol car waited for backup and then a white officer approached Jones and fired a Taser shot into his buttocks without trying to communicate with him verbally.

After the first shot from the Taser, Jones began flailing his arms and kicking his legs, but to the man watching the scene unfold, it was unclear if this was an attempt to fight the police or a reaction to the taser blast. In any case, he says the officers “bumrushed” Jones, taking him around the corner of the building, out of sight of the eyewitness and the video camera on the first patrol car. Steve Thrower, an investigator with the Jefferson County District Attorney’s office, disputes the eyewitness’ characterization of the struggle: “I’m not accusing him of being a liar, but he may have told what you wanted to hear.” Thrower declined to elaborate, but the witness has given a statement to the district attorney’s office. Martin Flood, a member of the city council who has taken an interest in this case, said that officers involved in the incident told him that Tyrone had fought back. “Four or five guys jumped on his back, and he raised up with all of them on his back,” said Flood.

An offense report obtained by the Observer lists Jones’ offense as “assault on a public servant,” but does not go into further detail. The report was both filed and approved by the same officer, Patrol Sergeant R.W. Harrison. Owens says that sometimes supervising officers will do this in order to expedite the entry of the report into the department’s computer system. However, a review of 330 PAPD offense reports covering a month-long period shows that no other reports had the same officer filing and approving reports.

The eyewitness lost sight of Jones and the police after they went around the corner but said he heard the officers asking Jones to put his arms behind his back and “three to four” loud pops—”like you opened up a bottle of wine”—a sound that is associated with Tasers. After about 30 minutes, he said the police began “hollering for an ambulance.” The technicians used a defibrillator on Jones to no avail. He was pronounced dead shortly after 11 p.m. The only people who had a clear view of what happened around the corner were several construction workers that Thrower says he did not interview and who subsequently left town. At press time, the results of an autopsy that might give more details of what took place that night had not been completed.

Family members believe the officers overreacted. “[The police] handled him like he was a criminal, but it was a medical situation,” said Alford, his sister. The family is preparing a wrongful death suit.

While the Jones incident may be the most serious example of police abuse in the wake of the hurricane, it’s not the only one. Allen Lewis, a 24-year-old life-long Port Arthur resident, recalls his bruising encounter with the law. Five days after the storm, Lewis, his cousin Broderick Kelley, and his uncle Billy Kelley, drove to Port Arthur from Dallas, where they had evacuated, to look for work and to check on their homes. (All three men are related to Hilton Kelley, the activist). The three went through two police checkpoints outside the city; the police didn’t tell them about the curfew, said Lewis.

When they arrived in town, they found a city without electricity and other basic services. First, Lewis checked at the Holiday Inn where he is employed to see if he could get back to work. The police had turned part of the hotel into a temporary jail. They asked him to leave, so the three men went to get a generator from the karate school Billy Kelley runs. While waiting for a ride from Billy (who had gone to get a car) near the school, a patrol car pulled up. An officer got out and, unprovoked, hit Lewis with the butt of his assault rifle, Lewis and Broderick say. The officer, listed as W. Crain on the arrest report, then slammed Lewis to the ground, which was littered with broken glass and called Lewis a “nigger,” according to Lewis and Broderick. In the process, Lewis’ face was cut with broken glass, he chipped a tooth, and received numerous abrasions. “Old boy was gung-ho,” recalled Lewis. “He was having fun.” At this point, Broderick, who had been watching from the shadows, came forward with his hands in the air. A black cop, Jeremy Houston (he was also involved in the Jones incident) was present for this altercation. Lewis yelled to Houston: “You goin’ to sit there and let him handle me like this?” Houston picked Lewis up and took him to the patrol car. He and Broderick were booked at the Jefferson County Correctional Facility on the charge of “violation of emergency management plan.” Approximately 50 other individuals were similarly charged a review of police records shows. Broderick and Lewis ran into Billy at the jail; he had been arrested 20 minutes before the two others on the same charge. They were put into a 10-foot by 10-foot cell with no electricity and foul water along with 10 other people, some of whom were refugees from New Orleans. The three were released on bail that night and told not to go back into town. They began walking toward Beaumont.

“[The hurricane] sorta gave those good ol’ boys who are still out there, ready to beat down any African American they can get their hands on… a prime opportunity and excuse for them to take advantage of a situation to create this martial law-type atmosphere,” said Billy Kelley. “[I]nstead of treating people like regular citizens, they started treating us like we were a bunch of criminals, a bunch of prisoners in this community.”

Port Arthur police declined to comment on the incident, but Deputy Chief Owens is dismissive of police abuse claims: “There’s no doubt in my mind there’s going to be people upset over how we handled the disaster response,” he says, but to do so would overlook the good work officers did after the storm from damage assessment to safeguarding infrastructure.

The Port Arthur Town Homes was also the scene of post-Rita looting and destruction. When residents began returning to their apartments after the storm they found notices on their doors that they had 30 days to vacate. In addition, they discovered that a restoration company, First Class Restoration of Houston, was already gutting their apartments to try to prevent mold from spreading. In many of the apartments, hot water heaters, toilets, cabinets, carpet, and even the sheetrock had been ripped out and either piled into the living rooms or thrown away, rendering the units unlivable, according to residents and Scott Moore, a worker with First Class Restoration. In the process, some of the renters’ personal items and furniture had been thrown away at the company’s discretion. Discarded mattresses, couches, clothes, and other items were still haphazardly piled in alleys behind the apartment buildings. Most troubling to the displaced renters, however, was that many of their valuables were missing, including cash, watches, and jewelry. After renters evacuated, out-of-town construction workers were housed in the apartments. Because the interior walls had been knocked out, the workers could move from room to room. Asked how valuables might have disappeared from the apartments, Moore responded: “Ain’t no telling.” Moore characterized the number of workers staying in the apartments as “one or two,” although at least one resident says there may have been as many as 20. An assistant manager of the complex acknowledged that some residents had complained to her of missing or stolen belongings but said that she doesn’t believe the company’s employees were responsible.

The apartment complex was not the only residence to sustain looting and other damage. Across town, in central Port Arthur, residents of a broken-down neighborhood tell of the difficulties, in the absence of outside help, of restoring even the most basic living necessities after the storm. Ladana Pressly, a large, gregarious woman, who is several months pregnant, pointed out the damage her home suffered: missing windows, broken doors, a leaky roof, downed trees in the yard, a power line that droops to the ground in her side yard, and signs of water damage inside the house. When Pressly returned to her home after evacuating, she also discovered that it had been looted. Someone had taken her hot water heater, air conditioner, and washer and dryer. The home of her neighbor, Herman Jones, is without a door, electricity, heating, or running water. Recently, Pressly and Jones said, a FEMA inspector assessed their homes and declared both of them “livable,” meaning that they are unlikely to be eligible for further assistance from FEMA. “They say [our home] is livable but we’ve got

ids and we can’t e

en take a shower,” said Pressly, adding that she does credit FEMA for quickly getting her the standard $2,000 in temporary assistance. (This was a common refrain even among Port Arthurians critical of some aspects of FEMA’s recovery efforts.) Frank Mansell, a FEMA spokesman, said that a “livable” house by the agency’s standards is one that is “safe, sanitary, and secure” with “essentials like running water, electricity, a furnace, and a lockable front door.” Meanwhile, Pressly is letting her neighbors and friends, including Jones, who are even worse off, stay at her house on cold nights.

To further the sense of abandonment in Port Arthur, FEMA has already left town. While nearby Beaumont and Orange still have FEMA disaster recovery centers where citizens can meet with FEMA personnel and file claims for assistance, Port Arthur’s center has been closed since October 28. Mansell said the closures were due to decreased demand as measured by foot traffic, but added that “there was some concern [the centers] may have closed too soon.”