Luck of the Irish

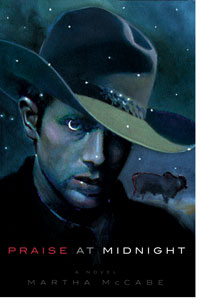

After graduating from Northeastern University Law School in Boston, Martha McCabe moved to Deep East Texas. It was the 1970s and the perfect setting for a young lawyer. Elsewhere in the South, the civil rights movement may have ebbed, but in Deep East Texas things were just getting started. For 11 years, McCabe worked on civil rights cases as a lawyer in private practice; by her own estimate, she heard some 5,000 people speak about their lives. Decades later, those stories would work their way into her subconscious and onto the pages of Praise at Midnight, her recently published debut novel (Word Wright International). Set in a fictional Deep East Texas town called San Bernardo, the novel is a complex portrait of a place that is burdened by historical divisions of race and class, city and country—a place where justice has always moved swiftly and predictably. Just months after the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Texas death penalty statute unconstitutional (1972), a young black man named Sherwin Ellis is charged with the murder of Ed Covey, a motel owner who dabbled in loan sharking. Stepping in as special prosecutor is Hayden Shipley, the town’s leading lawyer, who is also having an affair with the defendant’s cousin. Representing Ellis is 28-year-old Bill Mermann, a hapless young man who ends up trying the case when the big time civil rights lawyer from Houston is mysteriously pulled away at the last minute. Added to the mix of characters are a county sheriff with a terrible secret; a circuit-riding judge biding time for an appointment to a higher court; and an FBI agent keeping tabs on the nascent civil rights movement—and on a senior U.S. senator known to engage in sex with some of the county’s loveliest young black women. Things get really interesting when, against all odds, the town’s lone Communist becomes an alternate juror.

McCabe began working on the novel while studying fiction at Texas State University, where she received her MFA in creative writing. She now lives in San Antonio and works as general counsel for the Alamo Community College District. She has also worked for several state agencies and as special assistant to former lieutenant governor Bob Bullock. Recently McCabe spoke to the Observer about life and law, Deep East Texas, and the art of writing fiction. Excerpts follow:

Texas Observer: You grew up in upstate New York but your family has longstanding Texas ties.

Martha McCabe: My mother’s family, the Bordens, came to Texas around the 18-teens. The big impetus to Irish immigration before the famine was the penal laws of the 1790s, which precluded Irish land ownership and voting. The three brothers carved out their niches, one was a surveyor and laid out part of the city of Houston. One had the first English newspaper in Texas, based in Galveston. Gail, my lineal ancestor, rambled around, failing in businesses here and there and running through an amazing number of wives. I think he buried four wives. He apparently was a dreamer and engaged in various efforts to make it big. It wasn’t until war presented the opportunity for maximum profit that he really hit the big time. He went up north at the outbreak of the Civil War and hooked up with a venture capitalist, as we would say today. And although my mother bridles at my adolescent use of the word, he stole—as far as we can determine—the technique for condensing milk that the Shakers had developed. Because the Shakers were godly people, they did not believe in recourse to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. So he got their technique, patented it, and the rest is history. That was the basis of the Borden Dairy Company. He wasn’t ever in the big leagues with the Fricks and the Harrimans and the Vanderbilts, but he did manage to get a toehold in the sweet life of the gilded age. He left Texas just prior to the Civil War and put his bets on the Union side. He became a war profiteer—as soon as he got the technique from the Shakers, the first thing he did was sell milk to the Union army. Like many another, he built the foundation of his fortune on a public contract.

TO: What brought you to East Texas as a young lawyer in the 1970s?

MM: 1974. There’s a bit of a story: I had a boyfriend at the time who was going to South Texas College of Law. I wanted to try cases and I didn’t necessarily want to be in a Legal Services or public services setting. I wanted to live in a rural area. That’s all I knew about what I wanted to do as a lawyer. So I started hearing about the work that was then being done by what was called the Voters League and, of course, the NAACP in the first wave of redistricting. You may recall that David Richards and Paul Ragsdale, who was then in the Texas Legislature—he was born in East Texas but he represented a district in Dallas—systematically went around the counties of Deep East Texas where there was a significant African American population and filed lawsuits in William Wayne Justice’s court to realign the city and county commission with the percentage of African Americans. It was exciting work, the first generation of voting rights cases, and people on all sides could tell that that was going to change the landscape of Texas politics. The courts were being used to support very strong movements for social change—as I would argue they are today in a different part of the political spectrum. So, that was the legal milieu into which I came as a young lawyer, although the necessity to make a living meant that I was more focused on my own individual clients and my own modest cases.

TO: Why were you so intent on practicing in a rural area?

MM: I spent a lot of my youth in rural New England. My parents were small-town people who had moved to bigger cities, like many Americans. I knew people who loved their land and loved their environment. When I moved to East Texas, [it was as if] I had moved back almost two generations—people were in the same situation as people of very advanced age whom I had known in New England, vis-a-vis literacy, vis-a-vis living in the country versus coming into town and getting the kinds of jobs that would require different skills. There were still many people who had had to drop out of school in the third and fourth grade in the Depression, who could not read or write and had grown up in very stern versions of Protestantism. There was a lot of stoicism and one respects that. Of course the straight-up, in-your-face racialism was extraordinary to me. I would say as a footnote that that’s not unique to Deep East Texas. It was just more straight-up and sanctioned and out in the open.

TO: The death penalty obviously figures prominently in Praise at Midnight. Was that work that you were involved in?

MM: No. In the acknowledgements I credit my 12th grade teacher. I had a remarkable junior high and high school education. When I was in 10th grade, every one of my teachers had a Ph.D. It was the last bloom of the kind of upper-middle-class Irish and other Catholic women who did not have any other outlet in the labor force. They went into the convent to get their education and to teach. My 12th grade project was to write on the death penalty. I thought I was hot stuff in my little Catholic school uniform in the New York State Law library reading the British report; the British had abolished the death penalty in 1953. There I was a few months shy of my 18th birthday and reading these dusty tomes about the best evidence of that time that had been accepted by the British judiciary and Parliament that showed that capital punishment was not a deterrent and it was not a cost-effective tool for any of the things that the legal system was set up to do. It was very important for me to hear it, but it ended up causing huge dinner-table fights with my father. My father was old-school. He thought that the cost-effective thing to do was to abbreviate all due process. I say that glibly because when you live in Texas, you have to figure out how to cope with living in a place with such a brisk trade in the capital punishment arena. I mean that with no disrespect of any side of the discussion or to the victims or to the perpetrators. But it resulted in a big ruckus at the family dinner table as I became more convinced by reading the experts of the British report. I sat with that knowledge and information. It lay dormant for a long time. I never wanted to do a death penalty case. I always thought of myself after a certain point as a journeyman lawyer and felt that anybody who was on trial for their life needed a master—and that wasn’t me.

I came across that wonderful William Humphrey story that Genie Summer [a character in the novel] refers to in her colloquy with Hayden Shipley. And in June 1973, there was an unbelievable floor debate in the Texas Senate on the subject of reinstating the death penalty after the Supreme Court had invalidated the Texas statute. Of course, the opponents of the death penalty were consistently outvoted. Then finally, Bill Moore [the late William T. Moore of Bryan, who served in the Senate for three decades] gets up and says that the Legislature should give the city of Huntsville an additional appropriation for all the extra electricity that they were going to need when they started executing people again.

TO: Where does the character of Genie Summer come from? You describe the elaborate efforts the local judicial system went through to keep her out of the jury pool. When she’s finally called, she gives one of the most succinct and effective arguments against the death penalty I’ve ever read. Was she based on someone you knew?

MM: One of the points of departure for my novel—and I say this with all due modesty, as a writer with a first novel and a genre novel at that is probably ill-advised to even mention a Nobel laureate in the same sentence as her own work—but Naguib Mahfouz, the great Egyptian novelist, has a very small novel called Miramar, set in Alexandria in a little rooming house. It was written around the time of the revolt of the colonels that brought Nasser to power and there was a great social upheaval—about which I’ve now said more than I know. But the characters in that book artfully and beautifully embodied different classes and interests and the people affected by that change. I was a little scared about Genie because I thought that maybe I embodied her with too much symbolic weight, and that she wouldn’t live as a person. But I think she does. She’s also the voice of what, for want of a better word, you might call the “Old Left”—and yet she speaks as a southerner. One of my favorite lines in the book is [Sheriff] Pliny Tate’s comment that there was a time when he knew more Communists than Republicans, but now the Communists are dead and the Republicans are on the rise. It’s not fashionable to mention, either on the left or on the right, that the Depression hit Texas so hard that quite a number of people seriously looked at the promise of more egalitarian distribution of wealth that the Communist Party promised. Genie is a faithful representative of that dying breed. I tried to do justice to their earnest desire to allocate social resources, people such as Emma Tenayuca and the pecan shellers in San Antonio. All throughout East Texas, there were people—African American as well as white and Mexican American—who saw [something] in those ideals. They held to the fact that the Depression had been so awful. Imagine all these children turning blue and dying from malnutrition. Those amazing photographs of Russell Lee. That’s where I wrote Genie Summer from. I kept going back to those Russell Lee photographs, looking at the eyes of the sharecroppers in those pictures and trying to see how people who had empathized with their abject poverty and hopelessness, how people who had been young in that experience, would have turned out.

TO: I wanted to ask you about the treatment of sex and race in the novel.

MM: I represented a lot of women who told me a lot of things. Now, nothing in the novel is a violation of attorney client confidence. But I realized that in the 11 years that I was there that I had listened to 5,000 people talk about their lives. I was out and about. I was at union halls, at civil rights meetings, at funerals—all kinds of settings. People know who’s sleeping with who. They know who’s somebody’s mistress. It’s clear that all that stuff goes on and that one of the perks of privilege is having a mistress who’s younger and prettier than a man has any right to expect.

I’ve been in Texas government for a long time and when I started writing the novel people started telling me things that they wanted to put in the novel—things that they could never say in their own voice. Many women have always known that there was a public and private morality—that whole Country and Western theme. All I did was put it more in the forefront.

I was sitting in a black funeral parlor once, waiting for somebody to come talk to me, and the woman who was the funeral director told me a story about how when a certain black woman had passed, a white man had sat out in his car the entire time. Didn’t come in to the service, but everybody knew that he’d been her lover. The funeral director was a woman of no illusions, but there was a certain—not tenderness—but a certain poignancy in what she was saying. That even though he had loved her and apparently had loved her for 20 years, because he was white he felt constrained to even pay his respects when she passed. If you were listening for that, you wouldn’t be disappointed. And I was always listening for that. I’ll tell you why. I grew up in Albany, New York, which had the longest-running political machine in the United States, longer than Chicago. The mayor who served for 43 years was a man named Erastus Corning III, heir to a vast fortune, a Yalie. He had a society wife—high-church Episcopal and all that. And he had an Irish Catholic, foul-mouthed, tough-as-nails, tough-as-a-boot, Irish girlfriend for 30 or 40 years, who was always referred to delicately as “the mayor’s confidante.” The other thing you’ve got to understand is that I was in a vulnerable position, but I was also in a very public position because I was in a small town and I was the lawyer on the other side. I’ll give you an example. One day I was in a dress sto

e. Picture this: H

re I am in one of the few places that I could try to escape from reality. I am in this nice women’s dress store, looking at the sales rack. And all of a sudden this disembodied voice comes through the dresses, “Ms. McCabe, Ms. McCabe. Don’t look up. Keep looking at the dresses. I have something I have to ask you.” So I keep looking at the dresses. She says, “My name is so-and-so.” She’s the wife of the Republican County Chairman. “He’s beating me. He’s abusing me. I don’t know what to do. I’m scared to death. I’m afraid he’s going to kill me.” It’s almost like a confessional in the old Catholic Church. I didn’t seek it out. People would come to me. Frankly there was always the possibility that one was being set up. The part in the novel about Bill Mermann [the young defense attorney] locking his car not because of what people would steal, but because of [incriminating evidence] that they could put in, was very real. Paradoxically, in a small town that was very safe, I did lock my car all the time. I did get death threats, bomb threats. I was an outsider and somewhat of an easy target. I just made up my mind that being white and being a lawyer was going to keep me from being shot and they would probably continue to pick on people who were more vulnerable than I was. At least that’s the story I told myself to not become immobilized.

TO: What kind of response to the novel have you had in East Texas?

MM: I really haven’t been out there with it. I have sent it to a few people, and one fellow who used to practice in Lufkin was at my reading in Austin the other night. He was laughing and telling people, “Yeah, we all thought she was a Communist.” But you know, that word was a bundle of things. It meant she’s not like us. She doesn’t think the way we think.

TO: So, were you naïve when you moved out there because you connected with rural New England and rural New York?

MM: No. I might have underestimated the naked upfront racialism that I encountered, but I think that being prepared to see the good in rural life—I don’t think being respectful is ever lost or ever wasted. I don’t think that coming in hating them or thinking that they were the devil incarnate would have helped. I was in front of juries. In the first six months of practice out there I had six felony jury trials. I had to find a way to talk to people. How can you talk down to them and feel superior and expect them to help you and help your clients?

TO: You had all these stories for so many years. Were you taking notes or keeping a diary?

MM: No. What happened was that when I started writing, all these stories must have been lurking somewhere and I tapped into them, even though it’s been 30 years. The characters just started talking to me. Probably the reason that so many lawyers have become writers is that when you’re a lawyer you’re a storyteller for other people. People bring to you their stories in a heap—like in a grocery sack. You have to put them out on a table and put it together. I came to a point that I realized I wasn’t going to live forever and wanted to tell a story that I more or less controlled. I had an opportunity to go into the writing program [at Texas State University], which was wonderful. What I consciously did was try and understand how to use the conventions of fiction to tell the stories that I had been telling in the conventions of the oral tradition. Mainstream fiction taps into such a narrow, narrow, narrow, tiny little vein of American life. And here I had this missing world—missing in the sense that it’s not well represented in contemporary U.S. fiction—of Shakespearian language and great logos, pathos, and ethos waiting to be mined. What luck!