Indescribable Horror, Circa 1927

Indescribable Horror, Circa 1927

BY JAMES E. McWILLIAMS

The simplest lesson of the New Orleans disaster might be something like this: storms are perfect, but humans are flawed.

When Katrina’s surge overwhelmed the levees, tens of thousands of America’s poor, most of them black, lost everything. The President of the United States grimaced with false sincerity and tried to stay on vacation. The Vice President did stay on vacation. The Secretary of State, a black woman from Alabama, shopped for shoes at Saks Fifth Avenue. The Secretary of Defense, a man whose judgment seems permanently fogged, explained that the clean-up was proceeding well. The head of Homeland Security said the homeland was secure and encouraged charitable giving. FEMA’s director—called a ridiculous nickname (“Brownie”) by the President during the crisis—said that he knew nothing about refugees languishing in the New Orleans convention center. It was, to be generous, a glaring and almost farcical example of human beings on their absolute worse behavior.

Meanwhile, Katrina wreaked perfect havoc: “[T]he water just came in waves, just like a big breaker in the ocean, coming over this land. It was a really frightening thing to see something like that. It just came right over and rolled over.” To put it another way, “The situation is far worse than can possibly be imagined from the outside. It is the greatest disaster to come to this section and we need help from the federal government to prevent the worst kind of suffering.”

“FOR GOD’S SAKE SEND US BOATS!” a headline in the Times-Picayune screamed, followed by a story that explained, “It would be impossible to overestimate the distress of the stricken sections of the state. Back from the levees, where the land is flooded by backwaters, people are living on housetops, clinging to trees, and barely existing in circumstances of indescribable horror.”

What makes the flawed response to Katrina particularly galling goes beyond the unavoidable suspicion that white stockbrokers wouldn’t have been allowed to rot in the convention center. It’s that storms are predictable events. For a Gulf Coast city built below sea level and surrounded by a lake, an ocean, and the world’s most powerful river, it’s not a question of “if” but “when.” Federal and state authorities knew—and have always known—that the correct answer was “often,” but the levees went neglected and the rescue effort lollygagged. Officials should have known better, or at least known their history better.

After all, the storm descriptions in the previous paragraphs were not made in response to Katrina, but to the famous Mississippi flood of 1927.

John Barry’s Rising Tide, first published in 1997, vividly recounts this event. As Katrina pummeled New Orleans, Barry’s book shot to #11 on Amazon’s sales list, and Simon & Schuster ordered the publication of 10,000 new copies. While his riveting account doesn’t necessarily show the past presaging the present, it drives home an enduring point: the flaws of our leaders are magnified when the waters rise and the levees strain. Barry reminds us that while nature cannot be controlled, its most lacerating effects can be minimized if—a big if—public officials and scientists sacrifice self-interest to the common good. But as he also reveals, for all the generosity that individual Americans show when their neighbors are in need, public virtue is often missing in action.

John Barry’s Rising Tide, first published in 1997, vividly recounts this event. As Katrina pummeled New Orleans, Barry’s book shot to #11 on Amazon’s sales list, and Simon & Schuster ordered the publication of 10,000 new copies. While his riveting account doesn’t necessarily show the past presaging the present, it drives home an enduring point: the flaws of our leaders are magnified when the waters rise and the levees strain. Barry reminds us that while nature cannot be controlled, its most lacerating effects can be minimized if—a big if—public officials and scientists sacrifice self-interest to the common good. But as he also reveals, for all the generosity that individual Americans show when their neighbors are in need, public virtue is often missing in action.

Barry begins his tale of irresponsibility with the levees. In the mid-19th century engineers became gods, who came to believe that man could conquer nature. Entrusted with the task of managing a river often bloated to excess by concentrated rainfall, engineers in the private and public sectors sought bold solutions. Their differing answers to nature’s onslaught—answers from which they would not budge—involved some precise combination of levees, “cutoffs,” reservoirs, jetties, and the creation of outlets to relieve pressure from a growing river. For all their animosity, the competing engineers, raised in the “age of objectivity,” knew that “science . . . does not compromise.” They were after the Truth and—in an age when one of every four bridges built in the United States collapsed—each engineer somehow thought he’d found it.

Barry begins his tale of irresponsibility with the levees. In the mid-19th century engineers became gods, who came to believe that man could conquer nature. Entrusted with the task of managing a river often bloated to excess by concentrated rainfall, engineers in the private and public sectors sought bold solutions. Their differing answers to nature’s onslaught—answers from which they would not budge—involved some precise combination of levees, “cutoffs,” reservoirs, jetties, and the creation of outlets to relieve pressure from a growing river. For all their animosity, the competing engineers, raised in the “age of objectivity,” knew that “science . . . does not compromise.” They were after the Truth and—in an age when one of every four bridges built in the United States collapsed—each engineer somehow thought he’d found it.

Or at least that’s what they said. The underlying reality was more subjective. How can a scientist, after all, distinguish himself when he agrees with his competitor? What’s to define him as a genius if he follows the consensus?

The Mississippi River Commission was in charge of massaging these egos into a single and easily implemented solution to manage the river. It was not, however, a “scientific enterprise,” Barry notes, but nothing more than a standard bureaucracy. And a bureaucracy, by its nature, seeks a middle ground “and adopts the compromise as truth and incorporates it into its being.” Scientists were serving their egos, and the commission, aiming to be what we would today call “proactive,” was serving the New Orleans business establishment. Two entities that should have worshipped together were honoring different gods. Because of this disconnect, the commission eventually took positions that ended up “combin[ing] the worst” of the solutions offered by the competing engineers. As a consequence, the flood of 1927 raged with perfect pitch.

In simplest terms, the commission seized on the idea that a river hemmed in by levees would scourge its own bed and scrape away ample room for flood water. Ironically, a levee-only policy was the only one that all the scientists “violently rejected.” Nevertheless, the commission proceeded to constrain the river within levees, “believing that the levees alone, without any other means to release the river’s tension, could hold within narrow banks a force immense enough to have spread its waters over tens of thousands of square miles, where millions of people would settle.” On a given sunny day, it appeared that they had achieved nothing less than a hubristic testament to man’s power over nature. But in April of 1927, their accomplishment proved to be nothing more than a flawed answer to nature’s perfection.

Deluged with heavy rains, the river began to swell in Cairo, Illinois. Soon small crevasses were pouring from the fortified banks as if they were sieves. The river, Barry writes, “was growing and swelling and rising in preparation, gathering itself for a mighty attack, sending out small floods as skirmishes to test man’s strength.” Then, in rural areas throughout Missouri and northern Louisiana, saturated levees turned to mush and collapsed. A witness recalled the event:

When the levee broke, water just came whooshing, you could just see it coming, just see big waves of it coming. It was coming so fast till you just get exited, because you didn’t have time to do nothing, nothing but knock a hole in your ceiling and try to get through if you could … People and dogs and everything like that [were] on top of houses. You’d see cows and hogs trying to get somewhere where people would rescue them … Cows just bellowing and swimming …

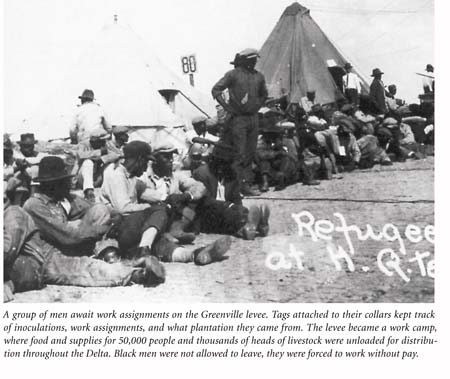

The people didn’t fare so well either. The crevasse that punctured the levees at Mounds Landing, Louisiana, for example, forced 185,459 people out of their homes, sent 69,574 to refugee camps for over five months, and soaked an area 50 miles wide and 100 miles long. On the lower Mississippi, land where over 930,000 lived quickly came under 30 feet of water. Covering an area larger than the states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Vermont combined, the flood would not dry up for another four months. No one knows how many died. They did know, however, that the levees were a horrible idea. They also knew that, in spite of Herbert Hoover’s heroic attempts to manage the disaster, they’d have to ride this one out and hope for the best.

But men in power generally don’t like to be at the mercy of anything, much less a storm. As the river coursed toward New Orleans, business leaders organized to enact a plan. “Louisiana waits,” the The Memphis Commercial Appeal warned, “with fear and foreboding.” What these men were considering as they cowered in a St. Charles mansion was a ruthless plan designed to keep investments in New Orleans secure (as the river swelled in the north, New York bankers were calling to see if the city was safe). As levees broke upstream, farmers suffered. But the pressure on the levees further south diminished as the surge spilled its artificial banks up north. Many observers correctly noted that the best bet—given the released pressure—would have been to do nothing. If authorities could have sat tight, the flood might have run its course without serious damage to New Orleans and its environs. But men being men, they prepared to make the worst of it.

Leaders in a crisis are supposed to act, if for no other reason than to give the appearance of doing something to solve the problem and keep investments from leaking out. So it was with the New Orleans establishment. Those who ran the banks and businesses, hosted the Mardi Gras balls, and determined who had political power and who kept it, wanted action. Cynically, they knew that a surefire way to ensure that New Orleans would be spared would be to dynamite the levee to the south, in St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes, thus releasing pressure at the point that would allow the river to slither past the Big Easy into the Gulf. In other words, sacrifice the country to save the city. The fact that this drastic act wasn’t necessary didn’t matter—the trailer trash to the south would pay the price so the business leaders could keep precious capital in the precious city that they controlled like cigar-chomping Mafia bosses.

Before they blew up their neglected back yard, the New Orleans elite, “as if on a picnic, traveled down to see the explosion” that would let loose a force of destruction displacing 250,000 cubic feet of water per second on the homes of hardworking farmers. After the three explosions created “a sudden Niagra Falls,” one leading resident of St. Bernard Parish turned to the press and announced, “Gentlemen, you have seen today the public execution of this parish.” As he spoke, the threatening waters of the lower Mississippi broke through levees and poured into tributaries that bypassed New Orleans and tumbled into the ocean, just as many engineers were predicting. “[T]he destruction of St. Bernard’s and Plaquemines was unnecessary,” Barry writes, “one day’s wait would have shown it to be so.”

There are plenty of lessons about geology, engineering, economics, and racism to be learned from the flood—as well as a lesson about expectations of heroism among public officials.

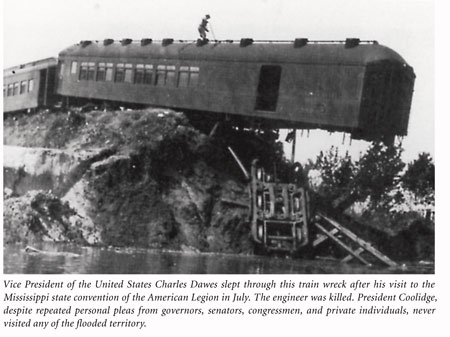

While the 1927 flood brought out the worst in many, one public figure stood above it all. Strange as it might seem, the hero was Herbert Hoover, a man who was placed in charge of coordinating rescue relief by the woefully indifferent President Coolidge. Hoover acted with urgency and compassion. He eliminated red tape. He muscled his way towards the center of supply trains and bellowed out orders for medicines and toilet paper. He used his position as commerce secretary to ask railroad companies to deliver supplies for free. Then he forgot he was commerce secretary and remembered he was a good man, tallying the number of people on rooftops and personally organizing their rescue. Tides will always rise to levels so deadly that engineers become afterthoughts—Hoover knew this. By placing the common good above all else, he embodied a spirit that the current administration cannot bring itself to acknowledge—even when the rest of the world shames America for its selfishness.

Hard to believe, but America longs for a Hoover.

James E. McWilliams is the author of A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America.