A Death in McAllen

What Noe Martinez Sr.'s death reveals about the nursing home crisis to come.

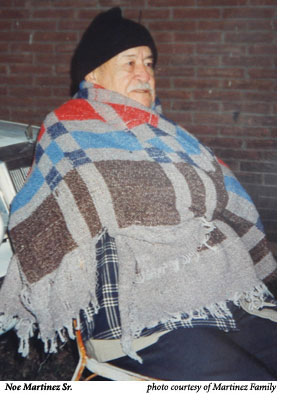

Alone in the nursing home, as Alzheimer’s devoured his mind, Noe Martinez Sr. fastened onto a sliver of memory he would never forget. His son’s name was worn into his mind. Before the nursing home, he had lived with his son, Noe Martinez Jr., for three years in their Edinburg home. A nurse had visited during the day. At night, though, it was up to Noe Jr. His father would call Noe Jr.’s name when he needed the bathroom or was hungry, which was often because of the diabetes, or when he couldn’t sleep. The son spent many nights in his father’s room, cajoling the older man to sleep. Eventually, the strain of caring for his dad and working demanding hours became too much. In March 2004, Noe Jr. and his sister Leticia decided to put their 77-year-old father in a nursing home. Even there, when he needed something, Noe Sr. would call out for his son.

Around 3 a.m. on July 4, 2004, at the McAllen Nursing Center, Noe Sr. yelled out for help. Perhaps he called for his son. He told the attendant that he was hungry. Noe Sr. no longer had any teeth and had been prescribed a diet of only pureed and soft food. When Noe Sr. asked for food that night, the person on duty, a vocational nurse, didn’t check the patient records. Despite the late hour, she went to fetch him something to eat: a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Without his dentures or even a glass of water, Noe Sr. choked on the food. He suffered his first heart attack at the nursing home. After paramedics revived him, a second and more serious one occurred at the hospital. When the Martinez family arrived, their father was brain dead. A respirator kept him alive. Doctors told Noe Jr. and Leticia that their father would never regain consciousness. It was hard to give up all hope, though. Sometimes his eyes would pop open. Doctors said it was because of a pressure build up. Sitting beside the hospital bed, Noe Jr. would close the older man’s eyes, only to see them flip open again. The eyes were lifeless, unmoving. After two weeks, they knew their father was gone, and they told doctors to remove the machine’s support. Noe Sr. died on July 17.

Their father’s premature death wasn’t caused simply by a single attendant’s negligence. Complicit is the entire system of nursing home care in Texas. Corporate owners such as the ones that run McAllen Nursing Center have little to fear financially if a vocational nurse or a poorly trained nurse’s aide negligently kills a patient.

Their father’s premature death wasn’t caused simply by a single attendant’s negligence. Complicit is the entire system of nursing home care in Texas. Corporate owners such as the ones that run McAllen Nursing Center have little to fear financially if a vocational nurse or a poorly trained nurse’s aide negligently kills a patient.

When Martinez family members tried to file a lawsuit following Noe Sr.’s death, they ran hard into one of Texas’ most controversial recent laws. In 2003, the state enacted sweeping legislation designed to transform the civil justice system. Among many other provisions, the statute capped damages for pain and suffering in all medical malpractice lawsuits, including those against nursing homes, at $250,000, removing a deterrent to bad behavior in the process.

The more politically connected nursing home companies had lobbied fiercely for the bill, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on building a new Republican leadership in the Texas Legislature. Now, Republican lawmakers in Washington, D.C., want to apply Texas’ litigation cap to the rest of the nation. GOP congressional leaders have composed their own civil justice reform bill that would cap all medical malpractice damages at $250,000 nationally. The legislation has passed the U.S. House but stalled thus far in the Senate. If it does pass, the federal cap would supersede all state malpractice regulations across the country.

Even as Texas capped the amount victims could win in court, the state’s oversight of nursing homes grew increasingly lax. During the past four years, there have been fewer inspections and penalties for even egregiously bad facilities. Taken together, these government policies ensure that Texas nursing homes that cut back on care to earn greater profits will suffer fewer consequences for their actions.

The death of Noe Sr. and his family’s difficulty holding anyone accountable for it reveal the outlines of a perversely designed nursing home system that fosters shoddy care. As the post-World War II population boom nears retirement age, the number of seniors entering that dysfunctional nursing home system will soon begin to soar. Many more seniors in Texas, and perhaps around the nation, may suffer like Noe Sr. and his family.

The genesis of Texas’ makeover of its civil justice system was the 2002 election. On November 5, 2002, Republicans in Texas celebrated resounding victories. A handpicked slate of Republican ideologues seized a majority in both chambers of the Legislature for the first time in 130 years. Since then, several Austin-based grand juries have investigated the election and how it was financed. The inquiry has laid bare which corporate interests donated to the Republican takeover. The public record shows how those interests subsequently benefited.

This past September 8, Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle announced that the grand jury had handed down five indictments, totaling 128 counts, against some of the most politically powerful organizations in Texas. The details of the scandal have been widely reported: a political action committee founded by U.S. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, known as Texans for a Republican Majority (usually referred to as TRMPAC), and the state’s largest business group, the Texas Association of Business (TAB), conspired to funnel millions of dollars in corporate funds into the 2002 state elections. However, it’s against Texas law to use corporate money for political purposes. So far, the grand jury has indicted the TRMPAC and TAB organizations, TRMPAC’s leaders, and a host of companies that supplied corporate funds for the campaign. Many of the indicted corporations are long-time political contributors: State Farm Insurance, AT&T, and Union Pacific Railroad. But the organization that provided the most corporate money to TRMPAC and TAB was an entity that most observers of Texas politics had never even heard of before 2002—something called the Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care.

Based in Washington, D.C., the Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care is a consortium of the nation’s 14 largest for-profit nursing home companies. It appears to be dominated by the nation’s third largest long-term care provider, Mariner Health Care, a $3 billion a year, Atlanta-based company that runs 250 long-term care facilities across the country, including 32 nursing homes in Texas. A Mariner executive named Kirill Goncharenko founded the Alliance in the late 1990s.

The Alliance lobbies Congress primarily to increase Medicare rates for nursing homes and to impose limitations on the civil justice system—an issue known in the peculiar parlance of public policy as tort reform. In late 2002, corporations and national advocates for tort reform were focused on the looming Texas elections: the first step toward passage of what they hoped would be landmark legislation. The Alliance helped lead the charge.

The Alliance lobbies Congress primarily to increase Medicare rates for nursing homes and to impose limitations on the civil justice system—an issue known in the peculiar parlance of public policy as tort reform. In late 2002, corporations and national advocates for tort reform were focused on the looming Texas elections: the first step toward passage of what they hoped would be landmark legislation. The Alliance helped lead the charge.

On October 21, 2002, about two weeks before the election, the chief executive of Mariner Health Care, Chris Winkle, had dinner at an upscale Houston restaurant with state Rep. Tom Craddick (R-Midland), the man Republicans hoped to, and later did, elect Speaker of the Texas House. The details of this meeting were first reported in September 2004 by Laylan Copelin in the Austin American-Statesman. At the dinner, Winkle gave Craddick a $100,000 check made out to TRMPAC on behalf of the Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care. Alliance officials have since said in several news accounts that they contributed to TRMPAC at the behest of their member nursing homes in Texas, which badly wanted the Legislature to enact tort reform. (Craddick has maintained that he did nothing wrong, telling Copelin, “I was just down there visiting with these people on their issues—election issues.”)

However, that wasn’t the full extent of the Alliance’s involvement. Three days after Winkle’s dinner with Craddick, the Alliance contributed another $300,000 in corporate funds to TAB’s electioneering efforts, according to the recently released indictments. Remarkably, some of that money may have made its way back to the Alliance’s founder, Goncharenko, who had left Mariner to help build the New York PR firm, Mercury Public Affairs. On October 25, 2002, the day after it received the $300,000 from the Alliance, TAB contracted with Goncharenko’s firm to create “issue ads” on behalf of two Republican legislative candidates in Texas, according to the indictments.

All told, of the roughly $2.4 million in corporate money handled by TAB and TRMPAC in 2002, about $400,000 of it—or about 17 percent—came from the Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care. That doesn’t include another $400,000 in PAC money that the nursing home industry gave the Texas Republican Party in 2002, including a $250,000 check from Mariner, according to the watchdog group Texans for Public Justice. By contrast, the nursing home industry gave $80,000 to Texas Democrats in 2002 (about a tenth of what it provided the GOP).

After the GOP took control of the Legislature and Craddick was elected speaker, one of the first items on the new leadership’s agenda was tort reform. The bill that passed the Legislature caps so-called non-economic damages—essentially, awards for pain and suffering—for each medical malpractice lawsuit at $250,000. (Twenty-three other states have restricted non-economic damages in some form, though few have enacted caps as low and as stringent as the ones in the Lone Star State.) In Texas, it was the insurance industry, hospitals, and doctors who had publicly clamored the loudest for the legislation. Nonetheless, the state’s GOP leadership specifically included nursing homes under the cap, devoting an entire section of the bill to the facilities.

Tort reformers in Texas insisted the law was necessary to reduce “frivolous lawsuits” responsible for the high medical malpractice rates that were driving doctors and other providers out of business. Like so much else surrounding tort reform, whether lawsuit abuse was really the cause of soaring premiums rates was fiercely debated in Texas. What wasn’t widely discussed was the cap’s potential impact on nursing homes. It should have been. Caps on non-economic damages disproportionately impact the elderly. That’s simply because most seniors don’t have jobs and can’t prove economic damages such as lost wages. The cap on non-economic damages means that the most that any senior neglected in a nursing home can receive in a malpractice lawsuit, no matter how horrific the abuse, is $250,000.

He could talk anybody’s ear off, Noe Martinez Jr. says of his father. Fit at 45, Noe Jr. has a mop of black hair and a black mustache. He’s sitting in an easy chair in the one-story Edinburg home that he shares with his sister Leticia and her husband. “Everyone around here knew him,” he says, sweeping a hand toward the front door. Almost everyone in downtown Edinburg knew Noe Sr. not because he was a civic leader or a public figure of any kind. He just liked to walk. He walked all over the city center, strolling from the neighborhood north of downtown in which he lived for years to the courthouse square and back. Noe Sr. was outgoing, and on his walks, he easily struck up conversations with people he barely knew.

He stayed nearly all his life in Edinburg. Born in nearby Mission, Noe Sr. served a stint in the Army at the end of World War II, though he never saw combat. After the war, he settled with his wife in Edinburg, working at an agricultural company outside town. His wife passed away in October 1965, and Noe Sr. never remarried, raising his six children as a single parent.

The first symptoms of Alzheimer’s are easy to miss. In the earliest stages, sufferers just seem forgetful, and when their father began to show signs of the sickness about 10 years ago, Noe Jr. and Leticia didn’t notice. Gradually, the symptoms became clearer. His memory lapses were more common, his walks less frequent. He began to call his grandson by the wrong name. One day, Noe Sr. drove off to visit his brother in town, only to return a short time later saying he couldn’t remember where his brother lived. “I said, ‘that’s it,’ and took his keys away and sold the car,” Leticia remembers. “For a year, he kept asking me about the car.”

After Noe Jr. moved in with his father in 2001, the older man’s health seemed to improve. Noe Jr. cooked healthy, balanced meals to keep his father’s diabetes under control, and the old man lost weight. His physical mobility improved. But while he remained physically healthy, his mind continued to falter. He soon couldn’t do basic tasks, like bathing, by himself. Noe Jr. rises for work at 4:30 in the morning to make deliveries for a fruit popsicle company in the Rio Grande Valley. His father’s calls for help became too frequent, and the nights awake comforting the old man started to take a toll.

The family admitted Noe Sr. to Edinburg Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center on March 29, 2004. Leticia knows the exact date. She kept a journal of all the pertinent facts regarding her father’s stay in nursing homes. In the beginning, it went well. Edinburg Nursing Home, the first of three nursing homes that Noe Sr. bounced through in just four months, seemed a clean, well-kept place in a scenic, leafy section of town. Noe Jr. noticed the blue and red flowers along the facility’s well-manicured grounds. “I thought if they have fresh flowers, they have to have people taking care of them every day. If they take special care of the flowers, they must be taking extra special care of the patients.”

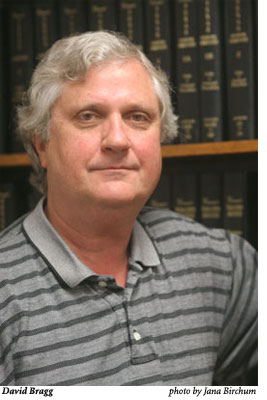

Austin plaintiffs’ attorney David Bragg believes that the civil justice system was the only mechanism in Texas in recent years that kept the worst for-profit nursing homes in check. Now that Texas has truncated patients’ ability to win damages in court, he fears no one is watching over the industry. A torrent of nursing home abuse, he says, is only a matter of time. He should know.

Austin plaintiffs’ attorney David Bragg believes that the civil justice system was the only mechanism in Texas in recent years that kept the worst for-profit nursing homes in check. Now that Texas has truncated patients’ ability to win damages in court, he fears no one is watching over the industry. A torrent of nursing home abuse, he says, is only a matter of time. He should know.

Bragg’s experience with nursing homes dates to 1977, when the state attorney general’s office responded to public outcry over widespread reports of abuse by tapping Bragg to head a nursing home taskforce. Bragg says the panel was the state’s first concerted effort to crack down on the worst of the nursing home industry in Texas. He returned to state regulation under Democratic Governor Ann Richards in the early 1990s. Now in private practice, he makes a living suing the industry he once regulated.

Seated in a conference room filled with law books in his downtown Austin office, Bragg argues that we have allowed dangerous trends to persist in the nursing home industry. Most families with the means these days increasingly keep their parents and grandparents out of nursing homes. Instead, they choose apartment-style assisted living facilities, in-home care, or adult day-care centers. That means, Bragg explains, that seniors who do end up in nursing homes truly have no place else to go; they are sicker and poorer—a more vulnerable population. And that makes them more expensive to care for, especially at a time of rising health-care costs.

While costs for nursing homes are going up, there’s less money coming in from state Medicaid programs. With state budgets so tight, Medicaid rates have been stagnant. Texas’ Medicaid rates for nursing homes rank 49th in the country. A 2003 study funded by the industry estimated that nursing homes spend $12 more each day on Medicaid patients than they receive in funding (in Texas, the estimate was a daily loss of $6 per patient). Because the vast majority of nursing home residents rely on Medicaid to pay their way, these trends make it increasingly difficult for nursing homes to make money. The less scrupulous for-profit nursing homes boost earnings by curtailing staff and services.

“Every dollar you spend on care is one less dollar available for profit,” Bragg says. “My friends in the nursing home industry tell me that if you’re a very good businessman, you can provide good care and you can make a small profit. But if you provide lousy care, you can make a lot of money.”

Worse yet, in Bragg’s view, even as nursing homes recklessly squeeze out more profits, safeguards in the system are crumbling. Bragg says there are three traditional ways to ensure quality of care in medical facilities: peer or doctor review, state regulation, and litigation. The first, Bragg flatly dismisses; unlike hospitals, nursing homes generally can’t do peer review. As for the second option: “[State] regulation is like a rollercoaster: it goes through ups and downs,” he says of the regulatory framework he helped design. “Now, we’re in a real down turn.”

The state’s own data bear this out. In 2001, the Legislature cut the state’s number of nursing home inspectors. About 20 percent of Texas’ 400 inspectors were reclassified as nursing home observers. These observers can visit nursing homes but are bureaucratically impotent: they can’t issue violations or warnings and can’t force nursing operators to show them records or patients. The result of this cut has been predictable: a gradual, across-the-board decline in every measure of nursing home oversight. By 2003, the number of visits to nursing homes by state inspectors had dropped 22 percent, before rebounding slightly last year, according to figures from the Department of Aging and Disability Services (DADS), the state agency that regulates nursing homes. Licenses denied by the department are down from 60 recommended denials in 2001 to eight last year. Administrative penalties are down roughly 75 percent. And perhaps most shocking are the number of facilities that the state has taken over and given to a court-appointed trustee to run: down from 21 in 2001 to 0—yes, zero—in 2004.

“This is the first time I can remember that we have none of the three legs of quality of care that we have historically relied on,” Bragg says. “Since 1980 or so, no matter what happened with [state] regulation, we’ve always had litigation as a backstop.”

McAllen Nursing Center is a low-slung, one-story brown brick building on the north side of town. Inside the front door is a large television room. Four white-tiled corridors branch off the circular nursing station like spokes on a wheel. By the time Noe Sr. entered the facility on July 1, 2004, he had bounced through two other nursing homes in just four months (both homes had given his room away during two stints in a hospital). In those few months, Noe Sr. went from a man who could walk mostly on his own to a virtual invalid who barely had the strength to sit up in bed. Noe Jr. believes that his father’s abrupt physical deterioration was due to an unhealthy diet at the nursing homes and the cocktail of medications they gave him. “All the medications poisoned his blood,” Noe Jr. says. “He slumped all the time. They had to brace him to his wheelchair.”

In most respects, McAllen Nursing Center is unremarkable. According to state records, it certainly doesn’t provide exceptional care, but sadly, neither is it the state’s most neglectful nursing home. State regulators score McAllen Nursing Center’s quality of care at 50 out of 100, according to state records. That’s below the state average score of 59, though other facilities consistently score in the 20s and 30s. Still, it’s clear from agency documents, obtained by the Observer, that plenty of abuse has been alleged against McAllen Nursing Center. In the three months preceding Noe Sr.’s death, the state received 29 complaints of abuse and neglect at the facility from residents and their families, according to internal agency documents. The complaints included accusations that residents waited for 45 minutes before an attendant responded to calls for aid; that staffers were belligerent with residents; and that the facility smelled of urine and feces.

State regulators investigated all 29 complaints and concluded that all but one of them were “unsubstantiated.” Usually, by the time state investigators arrived several days, or in some cases weeks, after the complaint was filed, the alleged problems had been cleaned up. (The one complaint that investigators did verify was a minor finding that the facility “failed to address patient grievances.” That didn’t prompt a violation or a fine.) In one instance, two aides at McAllen Nursing Center were accused of improperly and roughly handling a patient. The resident sustained bruises and a broken leg bone. When a state investigator arrived, the aides had been suspended, and the inspector couldn’t locate them for an interview. The complaint was filed as “unsubstantiated.” (After Noe Sr.’s death, however, state investigators found plenty of flaws with McAllen Nursing Center’s quality of care. Regulators thoroughly investigated the death, substantiating neglect and abuse by the nursing home. Regulators tagged the facility with three of its most severe code violations and fined it $2,000, offering a $700 discount if the facility paid promptly.)

In the immediate aftermath of their father’s death, the Martinez family had no idea that he had been the victim of neglect. They say nursing home and hospital officials simply told them that their father had choked and suffered a heart attack. The nursing home had fired the nurse who fed him the peanut butter sandwich. No one from the nursing home would explain why their father had choked. Noe Jr. says they couldn’t even obtain their father’s medical records.

The manager of McAllen Nursing Center at the time of Noe Sr.’s death has since left the facility. The new manager, Hari Namboodiri, referred all questions about the Martinez case to the facility’s corporate owners. McAllen Nursing Center is operated by an out-of-state management company, according to Secretary of State records. You need a flowchart and a business degree to discern who actually owns it. Many for-profit nursing homes use such complex corporate structures to protect their investors and owners from litigation. The facility is owned by McAllen Nursing Center LP, according to state records, which is owned by McAllen Nursing Center LLC (a holding company registered in Delaware). That is run by a third entity that’s owned by two men, Peter Licari and Michael D’Arcangelo of Horsham, Pennsylvania. Licari and D’Arcangelo own a management outfit that runs nursing homes in a handful of Northeastern states. They also operate 61 facilities in Texas, according to state records. An aide for Licari and D’Arcangelo referred all questions to Dallas attorney Nicole Bunn, who was vacationing in early September and couldn’t be reached for comment.

The Martinez family might never have known what happened to Noe Sr. if not for a McAllen police detective, who investigated the death. No charges were ever filed in the case. When the investigation was complete, the McAllen detective invited the family into the station house to read the police report. Leticia’s husband, Mario Millan, recalls, “He said, ‘This is gross negligence. Between you and me, if I were you, I would get an attorney.'” So the Martinez family set out to find a lawyer.

Like so much else in the tort reform debate, whether Texas’ damage cap is having a positive or negative impact on nursing homes depends on who’s talking.

To David Thomason, tort reform in Texas has been a success. Thomason is a lobbyist for the Texas Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, the Austin-based trade group for nonprofit nursing homes. Advocates for the elderly often describe nonprofits, many affiliated with churches, as the highest quality nursing homes because their mission is to care for seniors, not make a profit. Yet, in 2001 and 2002, many nonprofit homes were suffering, Thomason says, crumbling under high rates for liability insurance (just one company was offering policies in 2001). Unlike for-profits, most nonprofit nursing homes are required by their board to have liability coverage. Thomason cites one nonprofit home that saw its premiums increase so much that it had to choose between liability insurance and health insurance for its employees. It could afford only one. Eventually, the home solved the problem by laying off staff members.

Since the damage caps went into effect, Thomason’s nursing homes have reported a decrease in insurance rates and the number of lawsuits filed against them. These are hard facts to verify, though. No one has done a statewide review of malpractice lawsuits filed since 2003.

It’s also difficult to know whether insurance rates have gone down. The Texas Department of Insurance (TDI) barely regulates the liability market for nursing homes. The TDI estimates that 37 percent of facilities in Texas go without any liability coverage. Another 45 percent of nursing homes have coverage with out-of-state companies or use other plans that aren’t overseen by TDI. That leaves only about 85 nursing homes?out of more than 1,100 statewide?carrying insurance monitored by the state. Earlier this year, TDI surveyed 65 nursing homes and found lower premiums, but this sample size is so small that the data is almost worthless.

While the damage cap seems to have benefited insurance companies and nursing homes, trial lawyers have taken a hit. Austin attorney Jeff Rusk, who was at one time on a self-described crusade to regulate the industry in court, has stopped taking nursing home cases in Texas because of the damage cap. Rusk explains that suits against nursing homes are some of the most complex and expensive personal injury cases. It’s difficult to convince a jury that an elderly, and often sick, patient was neglected and that the victim lost years of a quality life. Proving this requires a bevy of medical experts and research into the patient’s medical history. All that costs money. Because the most a victim can be awarded is $250,000, and probably less, Rusk says he knows many attorneys who, like him, have decided these cases aren’t worth it. Other attorneys offer anecdotal evidence that the number of lawsuits filed and the number of attorneys taking nursing home cases are dropping. “It’s a devastating thing for the elderly,” Rusk says. “The only reason [nursing homes] looked over their shoulder was because of the civil litigation system,” he says. “The state was more of an annoyance. Now, you just have to trust them that even though it’ll cost them some of their profits, they’ll ramp up their staffing and take care of their patients. I don’t know about you, but I’m not that trusting.”

For Martinez family members, finding a lawyer to take their case proved more difficult than they expected. Family members contacted three medical malpractice lawyers in Edinburg and McAllen, only to be turned away each time. Their father’s case, seemingly an example of clear negligence, was too difficult to prove and wasn’t worth the effort, they were told. Frustrated, family members began calling all over the state in search of a lawyer. Finally, an attorney in San Antonio, Glenn Cunningham, agreed to represent them.

For Martinez family members, finding a lawyer to take their case proved more difficult than they expected. Family members contacted three medical malpractice lawyers in Edinburg and McAllen, only to be turned away each time. Their father’s case, seemingly an example of clear negligence, was too difficult to prove and wasn’t worth the effort, they were told. Frustrated, family members began calling all over the state in search of a lawyer. Finally, an attorney in San Antonio, Glenn Cunningham, agreed to represent them.

In late March of this year, about eight months after Noe Sr. died, Cunningham sent a notice of claim to McAllen Nursing Center’s corporate operators. The case was quickly settled. The agreement is confidential, and neither Cunningham nor the family would comment on the settlement terms. Cunningham, however, notes that he handled a case quite similar to Noe Sr.’s several years ago, before the damage cap was in place. Like Noe Sr., the victim in that case had choked to death due to staff negligence. “If anything, that case wasn’t as clear cut as [the Martinez] case,” Cunningham says. He settled that case for more than $1 million.

Insurance records offer hints to the Martinez family settlement. An Observer investigation has revealed that McAllen Nursing Center holds a $75,000 insurance policy. It’s common practice in the industry for nursing homes to settle cases for not much more than their insurance policies.

The Martinez family may not even get that. The state’s Medicaid program, having learned of the family’s settlement, wants a cut. The state has filed to recoup a chunk of the Medicaid benefits Noe Sr. utilized in his final years. Noe Jr. says the state’s effort would swallow nearly the entire settlement. Cunningham is fighting the request.

Noe Sr. would have turned 79 this September 4. More than 14 months after his death, his family hasn’t received a cent. Noe Jr. and Leticia are left with only regret. “You can’t describe the pain and the guilt,” Noe Jr. says. He stares out his living room window. “We tried to comfort each other that it seemed like the right decision. We trusted his life to them. [Nursing homes] should be regulated. I guess they are, but at least not enough.” He pauses. “It makes you wonder what’s going to happen to us.”

Additional Support for this story was provided by the Nation Institute.