Senatorial Courtesy

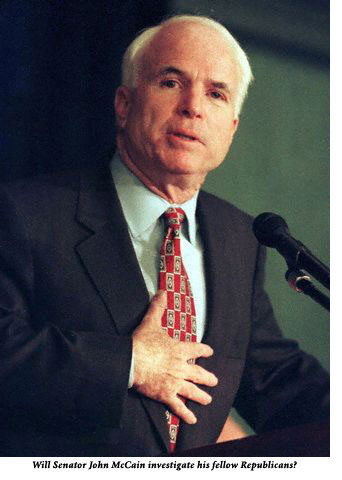

Will John McCain Let Republican Perps Walk?

On September 29, 2004, Arizona Senator John McCain made a promise to six Indian tribes defrauded in an $82-million lobby billing scandal perpetrated by two close associates of House Majority Leader Tom DeLay: “To the aggrieved tribes and Native Americans generally, I say rest assured that this committee’s investigation is far from over. Together we will get to the bottom of this.”

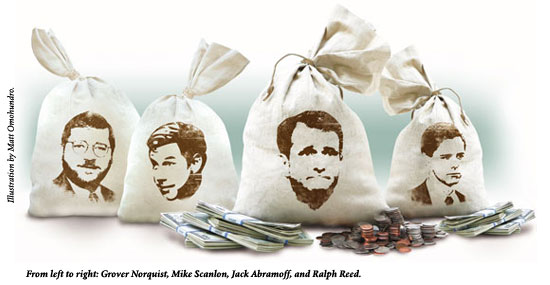

At the time, McCain probably meant what he said. But if he is to be a viable candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008, he may have to slow down the investigation he began a year ago. Because at “the bottom” of the inquiry McCain directs from the chair of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee is a second scandal that extends beyond the $82 million Mike Scanlon and Jack Abramoff took from the six tribes they were working for. Abramoff and Scanlon did more than enrich themselves. They enriched the Republican Party. The two Washington political operatives moved millions out of the accounts of the Indian tribes and into the accounts of Republican campaigns and advocacy groups whose support McCain will need for a presidential run in 2008. The personal contributions they made, such as the $500,000 check Scanlon wrote to the Republican National Governors Association in 2002, were derived from illicit billings of Indian clients.

McCain won’t antagonize Republican governors who know that Scanlon wrote the largest check they received in a critical election year. Nor does he seem inclined to cross Grover Norquist, the president of Americans for Tax Reform and arguably the most influential unelected leader of the Republican takeover of the Congress and White House. McCain has requested ATR’s financial and membership files and Norquist has refused to deliver them. Norquist claims McCain hates him. Perhaps. But Norquist’s unofficial position of power in Washington places him beyond the Senator’s reach. Norquist is not the only powerful Republican who would have to be questioned if McCain were to conduct a proper investigation. The list of subjects the Senator would have to take on includes Bush’s Interior Secretary Gale Norton; Bush’s 2004 Southeastern campaign director Ralph Reed, who once ran the Christian Coalition; the National Republican Governors Association; the Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee; and the Republican National Committee. All were recipients of large Indian contributions brokered by Abramoff. Majority Leader Tom DeLay had his hands in the Indians’ pockets and was the marquee name Abramoff used to sell his lobbying services to tribal leaders. Republican Congressman Bob Ney, who faces greater exposure to criminal prosecution than anyone except Abramoff and Scanlon, would be an immediate casualty of a proper investigation.

If Ney has the most to lose, Reed has the least to gain from his long, close relationship with Jack Abramoff. After leaving the executive director’s job at Pat Robertson’s Christian organization, Reed wrote Abramoff to ask for help in “humping” corporate accounts. Reed was instantly humping Indian tribes, as Abramoff paid Reed’s firm to direct anti-gambling campaigns designed to preserve regional Indian gaming monopolies. (Reed says he didn’t know the source of the money.) The millions Abramoff paid Reed was good for business but bad for electoral politics. Reed is starting his first campaign for public office, as a candidate for lieutenant governor in the Georgia Republican Primary. The McCain hearing, and the flood of internal e-mails it has released, comes at a bad time for him. In the end, even Abramoff and Scanlon soured on their go-to Christian, claiming he was overcharging them. “I’d like to know what the hell he spent it on-he didn’t even know the dam [sic] thing was there-and didn’t do shit to shut it down,” wrote Scanlon of a Texas casino. “I agree. He is a bad version of us!” replied Abramoff, adding “no more money for him.” McCain has shown no interest in calling Reed to testify.

Of even less interest to McCain-but of considerable interest to the defrauded Tigua Tribe of El Paso-is former Texas Lieutenant Governor Bill Ratliff. Ratliff got no contributions from Abramoff, Scanlon, or their Indian clients, according to filings at the Texas Ethics Commission. Yet he single-handedly killed a bipartisan bill that would have saved the Tigua casino in 2001. Killing the Tigua’s bill and casino made Jack Abramoff and his multi-million-dollar deal to reopen the casino the tribe’s last hope.

A few Democrats received contributions, most notably Rhode Island Congressman Patrick Kennedy, who as chair of his party’s congressional campaign committee, accepted a staggering $128,000 from the lobbyists and the tribes. But he was the exception. Abramoff and Scanlon have deep roots in the Republican Party. Most of the millions they contributed or pressured their tribal clients to contribute went to Republicans. So it’s difficult, perhaps impossible, for McCain to conduct the investigation he promised a year ago. Unless he decides he’s not a Republican candidate for the presidency in 2008.

“McCain wants to end the investigation,” said a source who has worked with the tribes and the Senate committee. “He hopes the grand jury will indict Abramoff, so he can say the investigation succeeded and wrap things up.” A U.S. attorney in Washington and a Washington grand jury began investigating Abramoff and Scanlon before they attracted the attention of the committee McCain chairs. That inquiry also seems to have been slowed down, according to one tribal source close to the investigation. “Everything seems like it slowed down as soon as Al Gonzales replaced Ashcroft,” he said. It could get slower. President Bush has appointed to the federal bench Noel Hillman, the section chief overseeing the Justice Department Public Integrity Unit conducting the investigation. (Abramoff’s six-count, wire fraud indictment unsealed August 11 is not related to Indian gaming, but to an allegedly fraudulent $23 million wire transfer in his purchase of a Florida gambling and cruise ship business. Abramoff did however rely on the support of DeLay and his staff to advance the deal. And Bob Ney entered a statement in the Congressional Record praising Abramoff’s venture and criticizing the previous owner, who disagreed with the terms of the purchase and who died in an unsolved, gangland-style shooting.)

The details of the Scanlon-Abramoff scandal have been reported here and in many other media outlets. In brief: Two lobbyists use their close association with majority leader Tom DeLay to book Indian clients, then bill at rates unheard of even in Washington. The story makes it to Page 1 of The Washington Post. A congressional investigation begins. DeLay denounces his longtime friend and advisor Abramoff and distances himself from Scanlon, who was his press secretary. McCain calls it all “disgraceful.” He is offended by e-mails in which Abramoff and Scanlon called their Indian clients “monkeys,” “troglodytes,” and “morons” and promises that Senate Indian Affairs will investigate.

Committee Chair Ben Nighthorse Campbell was in failing health and leaving the Senate. As ranking majority member in line for the chair, McCain ran the show. He began by releasing hundreds of pages internal documents and private communications. The pages are organized to create a compelling narrative, focusing on Reed and Congressman Bob Ney, among others. They even include a document implicating DeLay. “Mr. DeLay assists in raising money for a youth activity organization called Capital Athletic Foundation. All monies raised go directly to the Foundation and fund youth programs,” reads a November 2002 funding pitch Abramoff wrote. The same page also includes requests for money for the Republican National Committee and Norquist’s anti-tax group.

The White House couldn’t ignore the broadening scope of McCain’s investigation. Abramoff had raised $300,000 for Bush, been invited to a funders’ thank-you at a ranch near the President’s Crawford ranch (declined because he doesn’t travel on the Jewish Sabbath), served on Bush’s transition team in 2000, and had been to the White House on numerous occasions after Bush was elected. According to a source who has been interviewed by the FBI, Abramoff told tribal clients that he met regularly with Karl Rove, who insisted on meeting outside the White House so Abramoff’s name wouldn’t appear in public records. Norquist was selling casino Indians face time with President Bush for $25,000 a head. Bush’s Secretary of the Interior was changing Indian policy to accommodate Abramoff, at the request of DeLay and Speaker Denny Hastert. The scandal that started on K Street reached south toward Pennsylvania Avenue.

On November 17, 2004, McCain was called over to meet with the President, according to information provided by a Senate committee staffer. Regardless of the topic, the timing of the visit was a powerful message: the morning of the last Senate Indian Affairs Committee hearing on the lobbying scandal chaired by Nighthorse Campbell. McCain would not confirm the meeting. He later reassured his Republican Senate colleagues that he will not pursue members of Congress and would limit his investigation to the lobbyists and their money. Recently, he has demonstrated a reluctance to follow the money trail to power centers in the Congress, the White House, and his party.

A big part of this story involves a struggle between two tribes that have casinos at opposite ends of a long street: Interstate 10. Both tribes were clients of Jack Abramoff. On the east end of the street at $32 million, the Coushattas of Kinder, Louisiana, paid more than any other tribe for the services of Jack Abramoff and Mike Scanlon. On the west end of the street, the Tiguas of El Paso got the worst deal. The Coushattas were most concerned about the casino their East Texas cousins, the Alabama-Coushattas, were opening north of Houston. Houston is a big market for the Coushattas; billboards on I-45 and I-10 point the direction to the Coushatta casino, resort, and golf course near Lake Charles. The Tigua casino 950 miles away in El Paso was not competing with the Coushattas. But to kill the East Texas casino, the Coushattas had to eliminate all Indian gaming in Texas. They were counting on Texas Attorney General John Cornyn to enforce state law prohibiting all casino gambling. In September 2001 the El Paso casino that had lifted the Tiguas out of poverty was ordered shut down by a federal judge, ruling on a 1999 lawsuit filed by Cornyn. The Tiguas appealed. On the Coushattas’ tab, Abramoff hired Ralph Reed to work against the Tiguas. Reed organized public support for Cornyn’s lawsuit. E-mails released by Senate Indian Affairs establish that Reed, who was paid $4 million by Abramoff to work quietly to kill the casino, was in touch with the director of the criminal division in Cornyn’s office. (Cornyn has destroyed all his office e-mail correspondence regarding the litigation.)

While the decision was on appeal, Abramoff moved his fight to the Legislature, where bills were filed to legalize the state’s three Indian casinos if Cornyn prevailed. (The Kickapoos operated a small casino in Eagle Pass and the Alabama-Coushattas had a small one in Livingston, with big expansion plans.) Reed set up a front group in Houston to purchase radio ads, paid for phone banks to call state legislators, and used his Christian Coalition contacts to turn out pastors for the Senate Criminal Justice Committee hearing on the bill. Everything was done discreetly. As a prominent evangelical Christian, Ralph Reed couldn’t be seen accepting money derived from gambling, even if he was using it in an anti-gambling campaign.

Abramoff claims that Reed persuaded the acting lieutenant governor to kill the casino bill. In a February 2003 “Tigua Talking Points” memo Abramoff wrote: “last year we stopped this bill after it passed the House using the Lieutenant Governor (Bill Ratcliff) [sic] to prevent it from being scheduled in the state senate.” Abramoff got Ratliff’s name wrong. And by “last year,” he probably meant “last session.” But during the one session he served as acting lieutenant governor, Bill Ratliff, by himself, killed a bill written to save the casino.

Ratliff doesn’t deny that. He does deny that Abramoff or Scanlon in any way influenced him. “As lieutenant governor, you meet hundreds of people,” said Ratliff in a recent telephone interview. “I don’t recall meeting either one of them.” Ratliff talked to Ralph Reed during the 2001 session. But not about casino gambling. The topic of the meeting with Reed, Ratliff said, was redistricting. Ratliff said that because of his strong personal objection to gambling, he refused to recognize El Paso Senator Eliot Shapleigh when he tried to introduce the casino bill. Ratliff said the misspelling of his name in the e-mail indicates “how well those folks knew me.” Reed and Abramoff “were taking credit for something they didn’t do.”

Shapleigh says Ratliff broke a promise he made to the senators who elected him acting lieutenant governor when Rick Perry replaced George W. Bush. According to Shapleigh, several other Democratic senators, and a Republican Senate source involved in the lieutenant governor’s succession election, Ratliff made the promise at a meeting at the Four Seasons Hotel. He said that if 21 senators signed onto a bill, they would “have a run on the floor.” All bills in the Texas Senate are brought to the floor by a two-thirds vote of the 31 members. Shapleigh had more than two thirds. “I had twenty-three or twenty-four names on a card I showed Ratliff,” Shapleigh said. “He said he didn’t care how many votes I had. He wasn’t going to recognize me.”

The bill had been passed in the House by Rep. Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa, who was later elected to the Senate. Hinojosa had lined up 100 votes, but released some of his commitments because gambling is a tough issue for rural legislators. It passed the House with 83 votes. Shapleigh had the votes to pass it in the Senate. “Bill Ratliff defied the will of both houses of this Legislature,” Shapleigh said.

Ratliff is now lobbying and is in no way involved with McCain’s investigation. He says he never made the promise Shapleigh referred to and that he killed the bill because he believes “gambling is bad for the state of Texas.” By killing Shapleigh’s bill, Ratliff paved the way for a multi-million dollar fraud perpetrated on the Tiguas.

Ralph Reed’s work in Texas was a prelude to a $4.2-million package Abramoff sold the Tiguas. Reed was Abramoff’s front man. His public persona as a Christian evangelical provided him cover, should anyone ask what he was doing in Texas. After all, if Abramoff was to convince the Tiguas that he was the man to go to Washington and open their casino, he couldn’t be associated with shutting it down. The need for secrecy is evident in an e-mail he wrote to Scanlon when the tribe’s political consultant circulated Abramoff’s name: “that fucking idiot put my name on an email list! What a fucking moron. He may have blown our cover!! Dammit. We are moving forward anyway and taking their fucking money.”

Reed was never profane but he, too, had to be discreet. He denied knowing the source of the money Abramoff paid him. Gambling money is anathema to evangelical Christians. An e-mail Abramoff sent Reed after the final court ruling is the first indication that Reed knew where Abramoff earned his money: “I wish those moronic Tiguas were smarter in their political contributions. I’d love to get our mitts on that moolah.” Abramoff’s work wasn’t exactly a state secret. “Casino Jack,” as Abramoff was called, had the largest Indian account book of any lobbyist on K Street, where size and reputation matter. He had been profiled in major newspapers. And he and Reed were friends. It would have been a challenge for Reed not to know.

For Abramoff, Reed was useful beyond the Legislature. With the outcome of the lawsuit against the Tiguas still pending, he used his contacts in Attorney General Cornyn’s office to inform Abramoff of its progress. When the judge was set to hand down his ruling, Reed provided Abramoff the precise date. Fifteen minutes after receiving that information from Reed, Abramoff wrote to Scanlon. “Fire up the jet baby, we’re going to El Paso.”

Abramoff flew to El Paso to convince the tribe that he could get the Congress to reopen the casino that he had paid Reed $4 million to close. His fee would be $5.4 million-plus $300,000 in political contributions that he would control. The Tiguas countered with $4.2 million, and dutifully wrote checks for $300,000. At the initial meeting with tribal leaders Abramoff was asked if Reed had been involved in shutting down the casino. “Ralph does what Ralph does,” Abramoff said. He admitted that he and Reed were friends and longtime associates. He even suggested he could keep the tribe apprised of Reed’s anti-gambling work. While they were meeting, Abramoff received a message on his hand-held Blackberry. It was a brief note from Reed, describing his anti-gambling work in Alabama (which Abramoff and his Indian clients were also funding). Abramoff passed the Blackberry around the room, allowing the tribal leaders to read the message from Reed. The uncanny timing of that electronic message is one of many questions Senator McCain might ask Reed-if he were summoned to appear before the committee. He might also ask about the $10,000 Mississippi Choctaw contribution Reed received when he was running for Republican Party chair in Georgia. Or the $1 million in Mississippi Choctaw money Reed’s consulting company received to run anti-gambling campaigns.

There are a lot of questions that should be asked about Reed and what he might know about the Tiguas and Congressman Bob Ney. Yet at the most recent Senate Indian Affairs Committee, McCain ensured that question wasn’t answered. Toward the end of the June 22 hearing, North Dakota Democrat Byron Dorgan was questioning Amy Ridenour about allowing Abramoff to use the National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR) as a conduit for Indian money to pay for a golf trip to Scotland for Tom DeLay. Ridenour is the NCPPR president. Dorgan was also trying to get at a second golf trip-one that Abramoff and Ralph Reed had arranged for Congressman Bob Ney.

The NCPPR is a conservative policy group that gets much of its funding from tobacco and oil companies. Ridenour was at the witness table because her group had funneled $1 million from the Mississippi Choctaws to two organizations controlled by Abramoff. There had been no grant request, no accounting of how the money was spent, and no oversight of the spending. Ridenour did press Abramoff for something to satisfy a possible IRS audit, her e-mail pleas becoming more desperate after she read the first Washington Post account of Abramoff’s Indian lobby deals. Yet with $1 million, the largest grant NCPPR had ever received, Abramoff simply told Ridenour when the money was coming and where she was to send it.

“Sometimes that’s called laundering,” Dorgan said in his tentative effort to get the issue before the committee. Ridenour also took in $1.5 million from another Abramoff non-Indian gambling client, passing $1.28 million to another Abramoff company. She was even hustling more pass-through money to create the impression NCPPR was receiving large private donations. Abramoff wrote to Scanlon: “(they will give us back 100%) Let’s run some of the non-caf Choctaw money through them to the camans.” The FBI has subpoenaed NCPPR’s financial records. They will determine if “the camans” refers to offshore banks in “the Cayman Islands.” Amy Ridenour is a respected policy advocate and not Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno. But there appear to be serious problems with the way she has run her tax-exempt, non-profit organization. Yet McCain was obsequious in thanking her for appearing before the committee to “illuminate what appears to be a $1 million fraud.” That would be the fraud by which millions of dollars was moved through the organization she directs.

Toward the end of the June 22 hearing, Dorgan began to ask Ridenour about funding golf trips for Republican members of Congress. McCain turned in his chair and fixed an angry stare on his colleague. Dorgan got the message. After Ridenour deftly explained away the $50,000 in Indian money Abramoff moved through her office for Tom DeLay’s golf trip to Scotland, Dorgan retreated. “I won’t go further into this because it’s not part of the Choctaw issue itself, although I believe that a portion of the second golf trip was-I think Choctaw money was actually used to pay for a portion of the second golf trip.” A delegation of Choctaws capable of answering that question was sitting beside Ridenour at the witness table.

The second golf trip to Scotland-for Congressman Bob Ney, his staff, and Reed-is related to what might be a criminal fraud involving Abramoff, the Ohio Congressman, the evangelical political consultant, and the Tiguas. It appears that Ney tried to get the tribe, and other tribes, to pay for an expensive golfing trip to Scotland for about 10 people. If that request, and Abramoff’s request that the Tiguas send $32,000 to Ney and his PAC, influenced the performance of an official act, it is a violation of federal law. Soon after directing the Tiguas to send Ney $32,000 on March 20, 2002, Casino Jack was back. On June 7 he asked for as much as $100,000. In an e-mail to the Tiguas, Abramoff said “our friend” (Bob Ney) wanted to know “if we could help (as in cover) a Scotland trip for him and some of his staff (his committee chief of staff) and members for August.” The trip “will be quite expensive. I anticipate the total cost-if he brings 3-4 members and wives-would be around $100K or more.” Abramoff mentioned the earlier trip funded through Ridenour’s office-for “another member-you know who.” That was Tom DeLay. This time, the money would be laundered by Abramoff’s non-profit Capital Athletic Foundation.

The Tiguas were being strung along. Abramoff and Scanlon were promising that Connecticut Senator Chris Dodd would slip into his Help America Vote Act the language that would reopen their casino. The Tiguas were told Dodd was working in concert with Ney. In truth, Ney didn’t ask Dodd to help with the Tiguas until July 25. Dodd flatly refused. Abramoff might have actually believed he had Dodd bought. In an e-mail to Scanlon he reminds him to “get our money back from that motherfucker who was supposed to take care of Dodd.” Dodd was never in the deal.

On August 3, 2002, Abramoff, Reed, Ney, spouses, and staff traveled by private jet to Scotland. A former Bob Ney aide working for Abramoff also joined them. The trip to the legendary St. Andrews golf course was paid for by tribes that operated casinos or were attempting to open casinos. Together on the plane, in the hotel, and on the golf course were Abramoff, Reed, and the Ohio congressman who received $32,000 to help the Tigua’s deal along in Washington. Reed maintains he had no idea the trip was paid for with gambling money from the tribes. After the trip, Abramoff cautioned Tigua political consultant Marc Schwartz to avoid any mention of the trip when he met with Ney. “BN had a great time and is very grateful, but is not going to mention the trip to Scotland for obvious reasons. He said he’ll show his thanks in other ways, which is what we want.”

At an August 14 meeting with the Tigua tribal leaders, Ney thanked them for the golf trip. He was friendly and effusive, according to one source at the meeting. He told the Tigua leaders that he and Dodd remained committed to passing the measure that would open the casino. It wasn’t until October 8 that he told them that Dodd had “gone back on his word.” Abramoff seemed to believe his own cover story. “Dodd fucked us,” he wrote in a cheerless e-mail. “We’ve been fucked by a Democrat!”

“Knowing what you now know,” Dorgan asked Schwartz at the committee hearing last November, “do you believe that Mr. Abramoff and Mr. Scanlon and Mr. Reed perpetrated a fraud on your tribe?”

“I would say there’s no doubt that there was fraud,” said Schwartz.

Abramoff and Scanlon were summoned before the committee and exercised their Fifth Amendment right to remain silent. But they were already damaged goods. Reed, currently a candidate for lieutenant governor in the Republican Primary in Georgia, has not been asked to testify about his work in Texas. Nor did the Senate committee address in a public hearing the large contributions the tribe made to Republicans who have a lot more pulse left in them than do Abramoff and Scanlon:

$30,000 to the National Republican Congressional Committee $30,000 to the National Republican Senatorial Committee $30,000 to the Republican National Committee $25,000 for Council for Republican Environmental Advocacy, founded by Bush Interior Secretary Gale Norton and Norquist $20,000 for Montana Republican Senator Conrad Burn’s PAC 10,000 to California Congressman John Dolittle’s PAC $10,000 to Kansas Senator Sam Brownback’s PAC $10,000 to a PAC run by the Republican House Conservative Action Team $10,000 to Missouri Senator Kit Bond’s PAC

The $7,000 contributed to Majority Leader Tom DeLay and his PAC also seems to have escaped committee scrutiny. (Contributions are listed on Tigua documents obtained by the Observer, not documents released by the committee.)

It is a long list and a lot of money paid to influential Republicans. As fragmentary as it is, these are the small pieces of a much larger mosaic of money marshaled to leverage political power. The Tiguas gave the Council of Republicans for Environmental Advocacy (CREA) only $25,000. Yet CREA took in a grand total $250,000 from the six tribes, with the Coushattas contributing $100,000. Founded by Interior Secretary Gale Norton and Grover Norquist years earlier, and allowed to wither, CREA was resurrected by Italia Federici, a lobbyist who worked on Norton’s failed Senate campaign in 1996. In 2001 Federici abandoned CREA’s environmental mission to focus on Indian gaming. She called Interior Secretary Norton to arrange a meeting with the Coushatta tribal chairman in the spring of 2001. She didn’t get in. But shortly after the Coushattas made a $50,000 contribution to CREA, Federici persuaded Norton and her deputies to attend a CREA dinner party with Abramoff and then-Coushatta Tribal Chairman Lovelin Poncho, according to The Denver Post. Interior houses the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Norton has the final say on all Indian casino compacts. And the Coushattas’ casino compact was up for renewal in 2001. A separate Coushatta accounting document obtained by the Observer includes the note “Norton-Republican” beside Chairman Poncho’s order to cut a second, $100,000 check for CREA.

After reading his colleagues’ reporting, Post political writer John Aloysius Farrell set out in search of CREA’s Colorado offices. He found one of them occupied by a university comptroller and another by a flower shop. He concluded his column with a suggestion that John McCain track down the organization and knock on the door to inquire about the $250,000 in Indian gaming contributions. CREA’s D.C. office listed on the Tigua contribution ledger is 1429 G Street, Suite 408.

Thus far, McCain hasn’t knocked.

In May anti-tax activist Grover Norquist admitted to Boston Globe reporters that Americans for Tax Reform had served as a conduit to move Indian casino money to anti-gambling campaigns in Alabama. He even admitted that through 2004 he brought Indian tribal leaders to the White House to meet with President Bush. He insisted that he never linked contributions (in what seems to be the standard $25,000 denomination) to the privilege of meeting the President. E-mail correspondence and photocopies of checks obtained by the Observer strongly suggest that is not true. (See “The Pimping of the Presidency,” June 10, 2005.) The Observer has obtained copies of specific requests Abramoff made on behalf of Norquist, to the Coushatta and Mississippi Choctaws, offering up a meeting with the President for the price of $25,000 per tribal leader. And copies of the Coushatta check written to ATR.

The e-mails, checks, and accounting ledgers fit a larger pattern. Internal memos released by the Indian Affairs Committee on June 22 indicate that Norquist saw the Indians as another revenue stream for Americans for Tax Reform. On May 20, 1999, as Abramoff and Reed were preparing an anti-gambling campaign in Alabama, where casinos would threaten the Choctaws’ Mississippi casinos, Norquist sent an e-mail to Abramoff. “What is the status of the Choctaw stuff?” he asked. “I have a $75K hole in my budget from last year. ouch.” Norquist was soon moving Indian gaming money through Americans for Tax Reform, and taking what seems to be his standard $25,000 service fee. On one occasion Abramoff wrote to Reed to tell him $300,000 was on the way, but it would be “a bit lighter,” because he had to “give Grover something for helping.” Not to worry, however, with the next $300,000 transfer. Or so Abramoff thought. He followed with an e-mail to Reed complaining that “grover kept another $25K!”

Norquist, Reed, and Abramoff trace their political history back to the national College Republicans, where each of them served as director (as did Amy Ridenour). Reed started out as a College Republicans intern for Abramoff, who provided him a couch to sleep on in his D.C. apartment. They are still associates, still collegial, still Republican. And it was Reed who brought the three together on Abramoff’s Indian lobbying project. In November 1999 Reed wrote to Abramoff: “Hey, now that I’m done with the electoral politics, I need to start humping in corporate accounts! I’m counting on you to help me with some contacts. Have you talked to Grover since the Newt development. [sic] I’m afraid he took a hit on the consulting side with that since much of it was Newt maintenance…”

Norquist is a secular Republican with no religious reservations about gambling money. He was a useful middleman for Reed, who couldn’t take money directly from gambling interests and was eager to use ATR as a conduit. In e-mails Reed and Abramoff repeatedly discuss using ATR to move money. Approximately $850,000 out of the $1.5 million ATR received from Abramoff’s clients was forwarded to the Alabama Christian Coalition and then to Reed’s Century Strategies consulting firm. Another $300,000 went to another anti-gambling group in Alabama. Like Reed, the Alabama Christian Coalition never accepts money from gambling interests. E-mails between Reed and Abramoff establish that Reed knew he was being paid with Choctaw money. He did not, however, inform the Christian Coalition of the source of the $850,000 he re-routed through ATR. After the Globe reported the source of the money, Reed admitted he was paid by the Choctaws. But he insists he was paid only from non-gambling enterprises owned by the tribe. The Christian Coalition hired a Terre Haute, Indiana, law firm to conduct an independent investigation and was assured that none of the money it received from the Choctaws, via Abramoff, Reed, and ATR was derived from gambling at the Choctaws’ Mississippi casino. For the record, the Choctaws own the largest casino resort in the South.

Americans for Tax Reform continued to work the Indian revenue stream, asking through Abramoff for $25,000 sponsorships to bring tribal leaders to the White House. In September of 2002, for example, Abramoff e-mailed the Saginaw Chippewa political director to ask for money for two seats at the ATR White House event. “grover is really pressing me for the names of the tribes,” Abramoff said. Grover continued pressing until 2004.

There is no indication that the Senate Indian Affairs Committee will conduct a public hearing involving Norquist or Reed. There is still time. The Coushattas will tell their story at a final meeting expected in October, said a tribal leader. If properly told it will include another account of Abramoff and Scanlon using Indian money to bankroll the Republican Party. The hearing could provide a final opportunity to ask about the $150,000 the tribe contributed to CREA. There are other Coushatta contributions worthy of the committee’s attention. Tom DeLay’s ARMPAC received $45,000, though Abramoff requested the tribe divert $25,000 of it to Sixty Plus, an industry-funded advocacy group established to counter the work of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). Abramoff also re-directed $10,000 originally contributed to DeLay’s Texas PAC, TRMPAC, to America 21, a Tennessee Christian PAC supporting “Godly Candidates” and home-schooling, opposing abortion and the “Social Security Ponzi scheme.” America 21 is directed by former Idaho Congresswoman Helen Chenoweth-Hage. Kansas Senator Sam Brownback, who always seems to make the list, got $25,000. This accounting is very partial and based on documents obtained by the Observer. The committee has subpoena power.

While the Abramoff-Scanlon-Reed-Norquist story is big, the committee’s time limited, and Chairman McCain’s resolve questionable, it might still be worthwhile to explore one of the more perverse aspects of this sad account of lobbyists plundering Indian tribes. In 2003, when Abramoff and Scanlon had tapped out their Indian sources and were desperate for more money, they conceived of “The Tigua Elder Legacy Program.” As previously reported in the Observer, Abramoff planned to purchase term life insurance on Tigua elders and collect the death benefits as they died. It was an imaginative idea by which the deaths of tribal elders would pay for lobbying services for those left behind. It was also more than the Tigua Tribal Council could stomach.

In the summer before his Indian lobbying enterprise collapsed, Abramoff found another niche market to which the evangelical Reed could connect him: dying African-American Christians. If Reed could, as he promised Abramoff in an e-mail, deliver 85,000 Christian voters,” Abramoff must have assumed he could deliver enough dying black Christians to create a new revenue stream. In July 2003, Abramoff e-mailed Reed regarding “Black Churches Insurance program.”

“Per our previous discussion. Let me know how we can move forward to chat with folks who can set this up with African American elders. It can be huge.” Reed replied that it looked interesting and urged that they meet in D.C. as a next step.

A futures market that commodifies the waning lives of elder Black Christians. Who says this isn’t a great country?

Lou Dubose is a former Observer editor who began following Jack Abramoff, Mike Scanlon, and Tom DeLay two years ago while writing with Jan Reid the Public Affairs book The Hammer: Tom DeLay, God, Money and the Rise of the Republican Congress. This story was funded in part with a grant from the Fund for Constitutional Government, a publicly supported, charitable, nonprofit corporation established in 1974 to expose and correct corruption in the federal government.

End Times Tax Accounting

“No. Don’t do that. I don’t want a sniper letterhead.”

So wrote Jack Abramoff to his executive assistant at Greenberg Traurig’s Washington, D.C. lobbying office. An Israeli paramilitary organizer to whom Abramoff was sending high-tech military hardware had offered his sniper school letterhead to help comply with IRS requirements. Abramoff had spent $140,000 from his non-profit foundation to buy optics, stands, cases for sniper rifles, and a jeep for Schmuel Ben Zvi’s sniper school in the occupied West Bank. But the IRS allows educational foundation money to be used for educational purposes only, such as the Abramoffs’ Jewish day school in the D.C. suburbs. Ben Zvi, who despite the e-mail trail has since denied he ever knew Abramoff, suggested the Sniper Workshop letterhead and logo to accommodate the IRS. He was, after all, involved in education. He ran a sniper school in the ultra-orthodox settlement of Beitar Illit.

Keeping accounts straight was a frequent problem for Abramoff. His tax accountant warned, “military expenses don’t look good on the Foundation’s books.” It was also odd that money donated by the Mississippi Choctaw and the Saginaw Chipewas ended up training snipers in an Israeli settlement. But Abramoff was more concerned about moving hardware than cooking books. He was delighted when Ben Zvi wrote that they would expedite shipment by obtaining a signed letter from a paratroop brigade commander in the Israeli Defense Force. With the letter in hand, they could buy weapons from Raytheon and FLIR, and “end user” clearance from the U.S. State Department would be easier to obtain.

The “end user” wasn’t the Israeli Army. But Ben Zvi assured Abramoff he was still getting a bang for his buck. “The army for the most part creates soldiers, not WARRIORS,” Ben Zvi wrote. He talked of a fifth column of Jewish warriors that will someday issue its own “call to arms.” He also regaled Abramoff with accounts of sniper positions his group set up to cover IDF soldiers as they worked, “neutralizing” terrorists, and watching “the dirty little rats” on the Palestinian side of the fence.

Another e-mail from Ben Zvi suggests how the attack on the World Trade Center inflamed the radical settlers’ already overheated eschatology: “And parchas Balak in the Zohar says that before Moshiach comes three towers will burn in the gate of Rome (edom), I freaked out when I saw how the schematic drawing in Newsweek referred to the smaller (45 story) world trade center is referred to as the ‘third tower.'”

Like American End Times Christians who believe the 9/11 attack is an augur of the second coming of Christ, Abramoff’s End Times Israeli Jews believe the 9/11 attack anticipates the coming of the Messiah.

Abramoff’s CPA was so moved by accounts of sniper patrols in Beitar Illit that she decided they would somehow make the accounting work to satisfy the IRS. As always, Abramoff was ready to move: “Oh boy!” he writes to Ben Zvi. “Get me the letter from the army! Good Shabbos.”-LD