A Press Corps on the Lege

Forty years of covering the Texas Legislature

A Press Corps on the Lege

Forty years of covering the Texas Legislature

BY DAVE McNEELEY

![]() reported on my first session of the Texas Legislature in 1963, as a reporter for The Daily Texan, the student newspaper at The University of Texas-Austin. Since then, there have been a lot of changes, not only in the Legislature, but in the way the media covers it. Back then, there were no laws requiring open meetings and open records. A lot was done in secret. The chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, an old ex-alcoholic curmudgeon from Paducah named Bill Heatly, worked out the appropriations bill with a few cronies. They dropped the phone-book-size budget on everyone’s desk a couple of days before the end of the 140-day session. Legislators had a few hours to try to figure out what was in it—and what wasn’t. Lobbyists ran much of the show, from strongly influencing who became the speaker of the Texas House to writing legislation. The tongue-in-cheek rule for lobbyists in the House gallery was they could only vote on the voice votes. As a green reporter in an environment where relationships are everything, I had trouble finding out what was going on. The reporters in the know were the veterans who’d built up the trust and confidence not just of legislators and other public officials, but also of lobbyists. Trying to find out what was happening without those connections was frustrating. I blundered around enough that an older reporter dubbed me “Moose.” Press tables were actually located in the middle of the House floor. (During one particularly acrimonious debate in 1969, over a Senate proposal to put a sales tax on food, state Rep. Curtis Graves, a fiery black Houston Democrat, actually jumped up on the House press table to make his point. The tax proposal was shot down.) Most also were from that generation of people who had been through World War II, who referred to the government as “we” rather than “they.” Some reporters cycled into governors’ staffs as press secretaries and back into the press corps.

reported on my first session of the Texas Legislature in 1963, as a reporter for The Daily Texan, the student newspaper at The University of Texas-Austin. Since then, there have been a lot of changes, not only in the Legislature, but in the way the media covers it. Back then, there were no laws requiring open meetings and open records. A lot was done in secret. The chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, an old ex-alcoholic curmudgeon from Paducah named Bill Heatly, worked out the appropriations bill with a few cronies. They dropped the phone-book-size budget on everyone’s desk a couple of days before the end of the 140-day session. Legislators had a few hours to try to figure out what was in it—and what wasn’t. Lobbyists ran much of the show, from strongly influencing who became the speaker of the Texas House to writing legislation. The tongue-in-cheek rule for lobbyists in the House gallery was they could only vote on the voice votes. As a green reporter in an environment where relationships are everything, I had trouble finding out what was going on. The reporters in the know were the veterans who’d built up the trust and confidence not just of legislators and other public officials, but also of lobbyists. Trying to find out what was happening without those connections was frustrating. I blundered around enough that an older reporter dubbed me “Moose.” Press tables were actually located in the middle of the House floor. (During one particularly acrimonious debate in 1969, over a Senate proposal to put a sales tax on food, state Rep. Curtis Graves, a fiery black Houston Democrat, actually jumped up on the House press table to make his point. The tax proposal was shot down.) Most also were from that generation of people who had been through World War II, who referred to the government as “we” rather than “they.” Some reporters cycled into governors’ staffs as press secretaries and back into the press corps.  Texas was still a one-party Democratic state, which basically amounted to a no-party state. Since virtually everything was decided in the Democratic Primary, political organizations were largely personal, not partisan—though there was a perceptible divide between liberals and conservatives on issues like health care, education, and taxes. At that time in the House, representatives from major urban areas were elected at-large, countywide, by places, rather than in individual single-member districts. The result was that, to get elected, a candidate usually had to be a part of a business-oriented slate. As a result, most urban representatives were moderate to conservative Democrats. And the legislators largely did the bidding of the business forces that had financed their elections. (If you think that may be happening again today, you are not alone.) Television news was still in its infancy. Most Texans still got information about their state government from newspapers. Nearly all cities had two major daily newspapers, and each would generally have a person at the Capitol. The competition helped fuel coverage, but newspaper management was, for the most part, as business-oriented as the legislators. The good-old-boy system that permeated the Legislature also extended to the press, although some reporters resisted it. An exception was The Texas Observer, a liberal bi-weekly that carried often-scathing analyses about the underbelly of Texas politics and government. The iconoclastic populist organ, which helped spotlight such writers as Ronnie Dugger and Willie Morris, and later Molly Ivins and Jim Hightower, proved to be a continuing burr in the saddle of The Establishment, and one of the few places where liberals could see politics covered from their perspective. In what I have since come to call the Pre-Ethics Days—that is, before journalists began to draw a stricter line between the governed, the people who reported on them, and the lobbyists—the perks given to legislators in many cases also went to members of the Capitol press: Senior legislators had parking places on the Capitol grounds. So did reporters. Legislators had offices in the Capitol. So did reporters. The liquor lobby gave a couple bottles of whisky to legislators at Christmas—and also to reporters. The University of Texas gave free football tickets to legislators—and to reporters.

Texas was still a one-party Democratic state, which basically amounted to a no-party state. Since virtually everything was decided in the Democratic Primary, political organizations were largely personal, not partisan—though there was a perceptible divide between liberals and conservatives on issues like health care, education, and taxes. At that time in the House, representatives from major urban areas were elected at-large, countywide, by places, rather than in individual single-member districts. The result was that, to get elected, a candidate usually had to be a part of a business-oriented slate. As a result, most urban representatives were moderate to conservative Democrats. And the legislators largely did the bidding of the business forces that had financed their elections. (If you think that may be happening again today, you are not alone.) Television news was still in its infancy. Most Texans still got information about their state government from newspapers. Nearly all cities had two major daily newspapers, and each would generally have a person at the Capitol. The competition helped fuel coverage, but newspaper management was, for the most part, as business-oriented as the legislators. The good-old-boy system that permeated the Legislature also extended to the press, although some reporters resisted it. An exception was The Texas Observer, a liberal bi-weekly that carried often-scathing analyses about the underbelly of Texas politics and government. The iconoclastic populist organ, which helped spotlight such writers as Ronnie Dugger and Willie Morris, and later Molly Ivins and Jim Hightower, proved to be a continuing burr in the saddle of The Establishment, and one of the few places where liberals could see politics covered from their perspective. In what I have since come to call the Pre-Ethics Days—that is, before journalists began to draw a stricter line between the governed, the people who reported on them, and the lobbyists—the perks given to legislators in many cases also went to members of the Capitol press: Senior legislators had parking places on the Capitol grounds. So did reporters. Legislators had offices in the Capitol. So did reporters. The liquor lobby gave a couple bottles of whisky to legislators at Christmas—and also to reporters. The University of Texas gave free football tickets to legislators—and to reporters. ![]() watched in the 1960s and 1970s, as politics rapidly changed. In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that population among legislative districts had to be equal. The legislative elections that followed shifted a huge amount of political power from arid West Texas to well-watered East Texas, and from the country to the city. The Vietnam War polarized the country in the 1960s. Opposition was particularly fierce on college campuses. I was a pre-Baby Boomer, who stayed one step ahead of the draft—from student to marital to parental deferment, and then at 26, I was too old. But the war controversy energized student populations, including student journalists, who began to refer to the government as “they” rather than “we.” Some of those hot-blooded young reporters found their way into newsrooms, and some to the Texas Capitol. Another big catalyst for change was the Sharpstown scandal. In January of 1971, on the eve of the inauguration of Gov. Preston Smith and Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes to their second two-year terms, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission announced civil suits against Houston developer Frank Sharp and others for manipulating stocks. To get the banking and insurance legislation Sharp wanted, his manipulation scheme included goosing stock profits for several top Texas officials, including House Speaker Gus Mutscher and several aides, and Gov. Smith, who had bought stock with financing help from Sharp. Then, for the 1972 elections, the Supreme Court ruled that the largest Texas urban counties would no longer elect state representatives from countywide districts, but from single-member districts. Previously a legislative candidate had to either have the backing of the business cabal that financed the countywide elections, or be independently wealthy and willing to spend enough of his own money to compete. Suddenly a young upstart with a few thousand dollars and enough energy to wear out a few pairs of shoes going door to door could bypass The Establishment and get elected. That change, added to the Sharpstown taint, resulted in not just a new governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and House speaker, but also the largest freshman class in the Legislature in the 20th Century—71 House members and 16 of the 31 senators. Between the two chambers, the new legislators also included eight blacks, 12 Hispanics, 17 Republicans, and six women. They replaced some of the standard bourbon-swilling mossbacks who had run things. Though I was in Dallas during the early 1970s covering politics for The Dallas Morning News, I managed to talk my way to Austin so much that I almost lived there. I watched as the wholesale turnover in officials helped bring about, in 1973, what came to be called the “Reform Session” of the Texas Legislature. The new climate of openness was a response to the allegations of what amounted to backstairs bribes. A newly energized and aggressive Capitol press corps helped push the Legislature into opening up the system. The new laws required open meetings, open records, lobby registration, campaign finance disclosure, and other changes aimed at guarding the public trust. The new openness made it much easier for reporters to find out what was going on, even if some older legislators and lobbyists accustomed to working in the shadows found the sunshine uncomfortable. And the single-member House districts turned the lobby on its head. It went from a handful of lobbyists representing major industries choosing the House speaker, and then exercising top-down control with a few phone calls or conversations, to having to personally beg individual legislators for their votes. The new dynamics produced more “hired gun” lobbyists who handled groups of single issues and more team lobbying, as a black lobbyist, for instance, might more easily influence a black legislator than a white one. The demographics of the lobby began to rapidly resemble the new diversity in the Legislature—particularly as minority, female, and Republican legislators later became lobbyists themselves. The press changed accordingly. Since more legislators had seats at the decision-making table, there were more places to find out what was going on. The cozy relationship between newspaper management and state leadership cooled. A new openness, energetic reporters from the Vietnam-era, Sharpstown, and Watergate all contributed to ending the closed, clubby nature of the Capitol. In the 1970s, new media joined the fray, pushing up the level of discussion. Jim Lehrer launched frank-talking “Newsroom” on Dallas’s public KERA-TV. Mike Levy started Texas Monthly magazine in March of 1973, with then-unknown Bill Broyles as its editor. The Monthly combined some of the irreverent edge of The Texas Observer and the humor of its co-editors at the time, Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott, with slick fashion-magazine-style ads and much more popular entertainment. It rapidly became a political fixture, with a Bill Brammer story in one of its early issues on sex in the Capitol. In July—following the 140-day regular legislative session in odd-numbered years—the magazine published its picks of the Ten Best and Ten Worst legislators from the most recent session. In short order, being on the Best list was a big boon to re-election, and a place on the Worst list could help end a political career. (In later years, the mere presence on the House floor of the Monthly’s bulky Paul Burka, lead writer of the list for decades, would cause House members to actively, sometimes embarrassingly, lobby to get on the Best list, or stay off the Worst. That auditioning has extended in the Senate to Burka’s sidekick since 1989, Patricia Kilday Hart, a former Dallas Times-Herald reporter.) In 1974, hard-charging news director Marty Haag pushed WFAA-TV in Dallas to tougher reporting. The Los Angeles Times-Mirror took over The Dallas Times-Herald, and its new punchy reporting infused the stodgier Dallas Morning News with new energy. An often overlooked but significant change in the 1970s was the addition of more women, both in the Legislature and the press corps. Reporters, legislators, and lobbyists were largely a chummy bunch of guys who drank together and swapped stories—often about women. But as there were more women, different questions got asked.

watched in the 1960s and 1970s, as politics rapidly changed. In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that population among legislative districts had to be equal. The legislative elections that followed shifted a huge amount of political power from arid West Texas to well-watered East Texas, and from the country to the city. The Vietnam War polarized the country in the 1960s. Opposition was particularly fierce on college campuses. I was a pre-Baby Boomer, who stayed one step ahead of the draft—from student to marital to parental deferment, and then at 26, I was too old. But the war controversy energized student populations, including student journalists, who began to refer to the government as “they” rather than “we.” Some of those hot-blooded young reporters found their way into newsrooms, and some to the Texas Capitol. Another big catalyst for change was the Sharpstown scandal. In January of 1971, on the eve of the inauguration of Gov. Preston Smith and Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes to their second two-year terms, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission announced civil suits against Houston developer Frank Sharp and others for manipulating stocks. To get the banking and insurance legislation Sharp wanted, his manipulation scheme included goosing stock profits for several top Texas officials, including House Speaker Gus Mutscher and several aides, and Gov. Smith, who had bought stock with financing help from Sharp. Then, for the 1972 elections, the Supreme Court ruled that the largest Texas urban counties would no longer elect state representatives from countywide districts, but from single-member districts. Previously a legislative candidate had to either have the backing of the business cabal that financed the countywide elections, or be independently wealthy and willing to spend enough of his own money to compete. Suddenly a young upstart with a few thousand dollars and enough energy to wear out a few pairs of shoes going door to door could bypass The Establishment and get elected. That change, added to the Sharpstown taint, resulted in not just a new governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and House speaker, but also the largest freshman class in the Legislature in the 20th Century—71 House members and 16 of the 31 senators. Between the two chambers, the new legislators also included eight blacks, 12 Hispanics, 17 Republicans, and six women. They replaced some of the standard bourbon-swilling mossbacks who had run things. Though I was in Dallas during the early 1970s covering politics for The Dallas Morning News, I managed to talk my way to Austin so much that I almost lived there. I watched as the wholesale turnover in officials helped bring about, in 1973, what came to be called the “Reform Session” of the Texas Legislature. The new climate of openness was a response to the allegations of what amounted to backstairs bribes. A newly energized and aggressive Capitol press corps helped push the Legislature into opening up the system. The new laws required open meetings, open records, lobby registration, campaign finance disclosure, and other changes aimed at guarding the public trust. The new openness made it much easier for reporters to find out what was going on, even if some older legislators and lobbyists accustomed to working in the shadows found the sunshine uncomfortable. And the single-member House districts turned the lobby on its head. It went from a handful of lobbyists representing major industries choosing the House speaker, and then exercising top-down control with a few phone calls or conversations, to having to personally beg individual legislators for their votes. The new dynamics produced more “hired gun” lobbyists who handled groups of single issues and more team lobbying, as a black lobbyist, for instance, might more easily influence a black legislator than a white one. The demographics of the lobby began to rapidly resemble the new diversity in the Legislature—particularly as minority, female, and Republican legislators later became lobbyists themselves. The press changed accordingly. Since more legislators had seats at the decision-making table, there were more places to find out what was going on. The cozy relationship between newspaper management and state leadership cooled. A new openness, energetic reporters from the Vietnam-era, Sharpstown, and Watergate all contributed to ending the closed, clubby nature of the Capitol. In the 1970s, new media joined the fray, pushing up the level of discussion. Jim Lehrer launched frank-talking “Newsroom” on Dallas’s public KERA-TV. Mike Levy started Texas Monthly magazine in March of 1973, with then-unknown Bill Broyles as its editor. The Monthly combined some of the irreverent edge of The Texas Observer and the humor of its co-editors at the time, Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott, with slick fashion-magazine-style ads and much more popular entertainment. It rapidly became a political fixture, with a Bill Brammer story in one of its early issues on sex in the Capitol. In July—following the 140-day regular legislative session in odd-numbered years—the magazine published its picks of the Ten Best and Ten Worst legislators from the most recent session. In short order, being on the Best list was a big boon to re-election, and a place on the Worst list could help end a political career. (In later years, the mere presence on the House floor of the Monthly’s bulky Paul Burka, lead writer of the list for decades, would cause House members to actively, sometimes embarrassingly, lobby to get on the Best list, or stay off the Worst. That auditioning has extended in the Senate to Burka’s sidekick since 1989, Patricia Kilday Hart, a former Dallas Times-Herald reporter.) In 1974, hard-charging news director Marty Haag pushed WFAA-TV in Dallas to tougher reporting. The Los Angeles Times-Mirror took over The Dallas Times-Herald, and its new punchy reporting infused the stodgier Dallas Morning News with new energy. An often overlooked but significant change in the 1970s was the addition of more women, both in the Legislature and the press corps. Reporters, legislators, and lobbyists were largely a chummy bunch of guys who drank together and swapped stories—often about women. But as there were more women, different questions got asked. ![]() n 1971, I was working for The Dallas Morning News in Dallas. My close friend in the News’ Capitol bureau, Sam Kinch Jr. and his wife Lilas, volunteered to help my then-wife Saundra and me move with our kids from an apartment in University Park to a newly purchased house in Oak Cliff, a Dallas neighborhood. After we got the boxes moved, but not unpacked, Kinch and I hotfooted it to Love Field. There we were picked up by an oilman’s DC-3 on loan to Republican state Rep. Fred Agnich of Dallas, who had us flown to his fishing club in East Texas to play poker, shoot the breeze, and drink a lot of whisky—paid for, I guess, by lobbyists. Some of us even fished. (Our wives were so hacked off they decided the wives of the Capitol press corps would have their own retreat, and their husbands, thank you, could stay home and watch the kids. Beginning in February of 1972, once a year the wives retreated to a bed and breakfast or other place for some frivolity of their own they came to call The Mouton Hunt. Before the decade was out, the gathering was gradually transformed into the press corps wives and the women reporters. By the 1980s, as more and more women infiltrated the Capitol press corps, the women reporters outnumbered the wives.) Sometime during that period, one Capitol bureau chief, Scott Carpenter of Harte-Hanks, thought it improper that the press corps should get largely free digs in the Capitol. Carpenter, son of Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary Liz Carpenter, started arguing that news organizations should at least pay for their space according to market value, that close-up parking by the Capitol should be a perk that went the way of the Dodo Bird, and journalists should start rejecting the freebie favors from lobbyists. They should pay for their own drinks, meals, and travel to avoid the appearance that such gratuities influenced their stories. Gradually, and in some cases grudgingly, the press corps began to have to pay more than a pittance for their close proximity to the legislative chambers. Along with the change in how the Capitol press corps covered its beat came a physical transformation as well. As a cub reporter for The Houston Chronicle in the mid-1960s, I was among those within spitting distance of the House chamber. But after a 1983 fire damaged the Capitol, the building underwent extensive renovation. Part of the process involved excavating a 60-foot hole in solid limestone to build an underground extension behind the Capitol to the north. As part of the renovation, the Capitol press bureaus where I had been became part of the governor’s office, plus an equipment room. Most newspapers moved their bureaus south across 11th Street to 1005 N. Congress Ave. Although the renovation also put in a pressroom on the first floor of the underground extension, news organizations leased only a handful of the desks in the dungeon-like quarters, as a temporary jump-space. Most of the bureaus which represented out-of-town newspapers found it more efficient to consolidate their working offices in one place and walk the two blocks to the Capitol, than to be closer but in an underground space with no windows, some distance from the House and Senate floors, and away from the flow of lawmakers, staff, and lobbyists that used to provide convenient walk-up traffic. Most bureaus used their Capitol space only as an outpost to write when they were covering hearings or on a deadline. The Capitol renovation returned the main Capitol building to a majestic, high-ceilinged set of offices for senior legislators. And the new underground extension, with two floors of offices and meeting rooms, plus two floors of parking below that, gave even the most junior legislators offices with at least three rooms each. The downside was that the natural flow and friendliness that resulted from the crammed office suites of the 1960s and 1970s and the press outside the House chamber was much harder to find. Although the new underground cafeteria provides a good place to run across a variety of governmental sources, from legislators to staff to lobbyists to Supreme Court justices, the overall closeness of the earlier days declined measurably. A growing partisanship—exemplified by the current House Speaker Tom Craddick—has further rained on the camaraderie. Smash-mouth partisanship has also affected the journalism. Substance is often not as important as perception and spin-doctoring in the service of a particular ideological agenda. Reporters for the larger newspapers are conditioned to try

n 1971, I was working for The Dallas Morning News in Dallas. My close friend in the News’ Capitol bureau, Sam Kinch Jr. and his wife Lilas, volunteered to help my then-wife Saundra and me move with our kids from an apartment in University Park to a newly purchased house in Oak Cliff, a Dallas neighborhood. After we got the boxes moved, but not unpacked, Kinch and I hotfooted it to Love Field. There we were picked up by an oilman’s DC-3 on loan to Republican state Rep. Fred Agnich of Dallas, who had us flown to his fishing club in East Texas to play poker, shoot the breeze, and drink a lot of whisky—paid for, I guess, by lobbyists. Some of us even fished. (Our wives were so hacked off they decided the wives of the Capitol press corps would have their own retreat, and their husbands, thank you, could stay home and watch the kids. Beginning in February of 1972, once a year the wives retreated to a bed and breakfast or other place for some frivolity of their own they came to call The Mouton Hunt. Before the decade was out, the gathering was gradually transformed into the press corps wives and the women reporters. By the 1980s, as more and more women infiltrated the Capitol press corps, the women reporters outnumbered the wives.) Sometime during that period, one Capitol bureau chief, Scott Carpenter of Harte-Hanks, thought it improper that the press corps should get largely free digs in the Capitol. Carpenter, son of Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary Liz Carpenter, started arguing that news organizations should at least pay for their space according to market value, that close-up parking by the Capitol should be a perk that went the way of the Dodo Bird, and journalists should start rejecting the freebie favors from lobbyists. They should pay for their own drinks, meals, and travel to avoid the appearance that such gratuities influenced their stories. Gradually, and in some cases grudgingly, the press corps began to have to pay more than a pittance for their close proximity to the legislative chambers. Along with the change in how the Capitol press corps covered its beat came a physical transformation as well. As a cub reporter for The Houston Chronicle in the mid-1960s, I was among those within spitting distance of the House chamber. But after a 1983 fire damaged the Capitol, the building underwent extensive renovation. Part of the process involved excavating a 60-foot hole in solid limestone to build an underground extension behind the Capitol to the north. As part of the renovation, the Capitol press bureaus where I had been became part of the governor’s office, plus an equipment room. Most newspapers moved their bureaus south across 11th Street to 1005 N. Congress Ave. Although the renovation also put in a pressroom on the first floor of the underground extension, news organizations leased only a handful of the desks in the dungeon-like quarters, as a temporary jump-space. Most of the bureaus which represented out-of-town newspapers found it more efficient to consolidate their working offices in one place and walk the two blocks to the Capitol, than to be closer but in an underground space with no windows, some distance from the House and Senate floors, and away from the flow of lawmakers, staff, and lobbyists that used to provide convenient walk-up traffic. Most bureaus used their Capitol space only as an outpost to write when they were covering hearings or on a deadline. The Capitol renovation returned the main Capitol building to a majestic, high-ceilinged set of offices for senior legislators. And the new underground extension, with two floors of offices and meeting rooms, plus two floors of parking below that, gave even the most junior legislators offices with at least three rooms each. The downside was that the natural flow and friendliness that resulted from the crammed office suites of the 1960s and 1970s and the press outside the House chamber was much harder to find. Although the new underground cafeteria provides a good place to run across a variety of governmental sources, from legislators to staff to lobbyists to Supreme Court justices, the overall closeness of the earlier days declined measurably. A growing partisanship—exemplified by the current House Speaker Tom Craddick—has further rained on the camaraderie. Smash-mouth partisanship has also affected the journalism. Substance is often not as important as perception and spin-doctoring in the service of a particular ideological agenda. Reporters for the larger newspapers are conditioned to try

to balance th

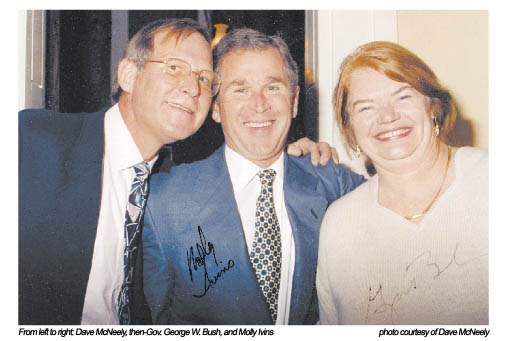

ir reporting with at least two sides, and so often find themselves used as tools for the partisan combat that is more and more prevalent in the Texas Capitol. ![]() here was a period in the 1970s, and particularly the 1980s, when Texas television stations were well represented in the Capitol news coverage. The leader was Belo Broadcasting, owner of stations in Dallas and Houston at the time. It had an active staff in Austin in the 1980s, headed by Carole Kneeland, until she left in 1989 to be news director at KVUE, the Austin ABC outlet. (Carole was also my wife for 15 years until her death of breast cancer in 1998. Her reporting and management skills were so good that a training program for news directors, The Carole Kneeland Project for Responsive Television Journalism—www.CaroleKneelandProject.org—was started as she was dying.) But during the late 1990s, television coverage subsided. Today, there are no non-Austin TV stations that regularly cover the Legislature. Although dozens of cameras will show up on opening day of the session or periodically for other big events, the day-in, day-out attention that produces the experience and wisdom to provide meaningful analysis of events is largely missing from the medium from which most Texans get their news. One by one, major cities saw their second-place newspapers fold, as they were bought out by their competitors—The Dallas Times-Herald in 1991, The San Antonio Light in 1993, The Houston Post in 1995. Some reporters, like the Post’s bureau chief Ken Herman, moved to other papers like The Austin American-Statesman. In 1984, Texas Weekly started as an attempt by Sam Kinch Jr., George Phenix, and John Rogers to pick up the slack from the newspaper consolidation, covering the political gossip and inner workings of state government. Ross Ramsey, a veteran newsman for The Dallas Times-Herald and then The Houston Chronicle, who worked briefly for Comptroller John Sharp in the 1990s, bought out Kinch in 1998. The Quorum Report, which was taken over by Harvey Kronberg in the early 1990s, has become a daily gossipmonger for on-line subscribers and others, even before the days of what are called “blogs” (short for weblogs). There is also the Lone Star Report, a publication largely financed by Austin banker David Hartman, a Republican who unsuccessfully ran for state treasurer in 1994. It provides a conservative take on news from the Capitol. The newest addition to the reporting mix is the blogs themselves. Several people have joined the reporting ranks simply by, in the computer age, honoring A.J. Leibling’s time-honored adage that “Freedom of the press belongs to those who own one.” In the e-mail and weblog era, virtually anyone can. It’s a fairly simple matter to get on the Internet and put up your own take on what’s going on and what it means—at least to those writing the blogs. Most of the blogs are from the left, though some are from the right. But in Texas, as well as nationally, sometimes the bloggers are first on the scene. As newspaper circulations decline, several major papers that once largely abandoned the scuttlebutt niche Kinch filled with Texas Weekly, are rapidly pushing their web pages. Some have started their own blogs to compete with the freelancing bloggers and newsletters. How well that will work is another question, since the newspapers’ blogs are in essence competing with themselves. But in a time when newspaper publishers realize they have to do something besides toss a wad of newsprint on your doorstep, they’ll do anything they can to try to keep people paying them to gather the news. So now, 42 years after covering my first session of the Texas Legislature, I’m back covering another one, though at a lesser pace. I still find the Texas Legislature eternally interesting, if somewhat repetitive in its subjects. To keep up, I may even have to think about blogging. Dave McNeely retired at the end of December from The Austin American-Statesman. He writes one column a week for 30 Texas newspapers and is co-writing a book on the late Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock with Jim Henderson. McNeely is happily married to the former Kathryn Longley. He can be contacted at [email protected] or 512-458-2963.

here was a period in the 1970s, and particularly the 1980s, when Texas television stations were well represented in the Capitol news coverage. The leader was Belo Broadcasting, owner of stations in Dallas and Houston at the time. It had an active staff in Austin in the 1980s, headed by Carole Kneeland, until she left in 1989 to be news director at KVUE, the Austin ABC outlet. (Carole was also my wife for 15 years until her death of breast cancer in 1998. Her reporting and management skills were so good that a training program for news directors, The Carole Kneeland Project for Responsive Television Journalism—www.CaroleKneelandProject.org—was started as she was dying.) But during the late 1990s, television coverage subsided. Today, there are no non-Austin TV stations that regularly cover the Legislature. Although dozens of cameras will show up on opening day of the session or periodically for other big events, the day-in, day-out attention that produces the experience and wisdom to provide meaningful analysis of events is largely missing from the medium from which most Texans get their news. One by one, major cities saw their second-place newspapers fold, as they were bought out by their competitors—The Dallas Times-Herald in 1991, The San Antonio Light in 1993, The Houston Post in 1995. Some reporters, like the Post’s bureau chief Ken Herman, moved to other papers like The Austin American-Statesman. In 1984, Texas Weekly started as an attempt by Sam Kinch Jr., George Phenix, and John Rogers to pick up the slack from the newspaper consolidation, covering the political gossip and inner workings of state government. Ross Ramsey, a veteran newsman for The Dallas Times-Herald and then The Houston Chronicle, who worked briefly for Comptroller John Sharp in the 1990s, bought out Kinch in 1998. The Quorum Report, which was taken over by Harvey Kronberg in the early 1990s, has become a daily gossipmonger for on-line subscribers and others, even before the days of what are called “blogs” (short for weblogs). There is also the Lone Star Report, a publication largely financed by Austin banker David Hartman, a Republican who unsuccessfully ran for state treasurer in 1994. It provides a conservative take on news from the Capitol. The newest addition to the reporting mix is the blogs themselves. Several people have joined the reporting ranks simply by, in the computer age, honoring A.J. Leibling’s time-honored adage that “Freedom of the press belongs to those who own one.” In the e-mail and weblog era, virtually anyone can. It’s a fairly simple matter to get on the Internet and put up your own take on what’s going on and what it means—at least to those writing the blogs. Most of the blogs are from the left, though some are from the right. But in Texas, as well as nationally, sometimes the bloggers are first on the scene. As newspaper circulations decline, several major papers that once largely abandoned the scuttlebutt niche Kinch filled with Texas Weekly, are rapidly pushing their web pages. Some have started their own blogs to compete with the freelancing bloggers and newsletters. How well that will work is another question, since the newspapers’ blogs are in essence competing with themselves. But in a time when newspaper publishers realize they have to do something besides toss a wad of newsprint on your doorstep, they’ll do anything they can to try to keep people paying them to gather the news. So now, 42 years after covering my first session of the Texas Legislature, I’m back covering another one, though at a lesser pace. I still find the Texas Legislature eternally interesting, if somewhat repetitive in its subjects. To keep up, I may even have to think about blogging. Dave McNeely retired at the end of December from The Austin American-Statesman. He writes one column a week for 30 Texas newspapers and is co-writing a book on the late Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock with Jim Henderson. McNeely is happily married to the former Kathryn Longley. He can be contacted at [email protected] or 512-458-2963.