The Art of Capital Punishment

The Art of Capital Punishment

BY PATRICK TIMMONS

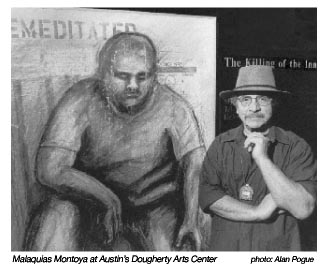

Premeditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment, Recent Works by Malaquias Montoya Dougherty Arts Center, Austin, January 5–30 Instituto Mexicano, San Antonio, February 17–28 ![]() ’ve always been against the death penalty,” says Malaquias Montoya. “I’ve just never been an activist.” Perhaps not an anti-death penalty activist, but Montoya, who teaches at the University of California-Davis, has long been considered a leading figure in social protest art. He is best known for public murals, silkscreen images, and offset lithograph posters decrying a trio of global evils: imperialism, racism, and sexism. Recently he came to Austin to introduce his latest work, which focuses on capital punishment. As he explains, during the 2000 presidential election he became aware of Texas’ high execution rate under then-Governor Bush and was inspired to illustrate his feelings about what he refers to as “state-sanctioned killings.” Premeditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment, Recent Works by Malaquias Montoya unites in a single room more than 20 images depicting the development of capital punishment in the United States since the late 19th century. As the catalogue text indicates, Montoya “does not produce his art for the purpose of selling, he does not exhibit in commercial galleries, and he is suspicious of museums.” But he does want to reach people—particularly people who will be motivated to contact their legislators.

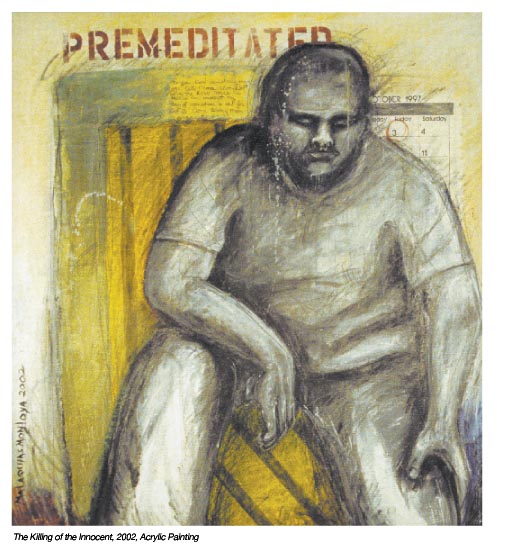

’ve always been against the death penalty,” says Malaquias Montoya. “I’ve just never been an activist.” Perhaps not an anti-death penalty activist, but Montoya, who teaches at the University of California-Davis, has long been considered a leading figure in social protest art. He is best known for public murals, silkscreen images, and offset lithograph posters decrying a trio of global evils: imperialism, racism, and sexism. Recently he came to Austin to introduce his latest work, which focuses on capital punishment. As he explains, during the 2000 presidential election he became aware of Texas’ high execution rate under then-Governor Bush and was inspired to illustrate his feelings about what he refers to as “state-sanctioned killings.” Premeditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment, Recent Works by Malaquias Montoya unites in a single room more than 20 images depicting the development of capital punishment in the United States since the late 19th century. As the catalogue text indicates, Montoya “does not produce his art for the purpose of selling, he does not exhibit in commercial galleries, and he is suspicious of museums.” But he does want to reach people—particularly people who will be motivated to contact their legislators.  The violent subject matter of Premeditated demands a meditative space, one that allows lengthy, directed contemplation of difficult questions. Montoya begins this conversation with the viewer by asking, “Why do we kill? And what happens to us as a humanity, as a culture?” In paintings such as The Execution of the Innocent or The Execution of the Mentally Retarded, the viewer is asked to consider the moral implications of state power, a question that resonates strongly in a state that is the epicenter of America’s modern death penalty experience. Montoya’s death penalty art derives edgy rawness from his belief that “revenge doesn’t bring anything.” But revenge does make for emotionally disturbing art, as is apparent from the observations of visitors to the Dougherty Arts Center. “Powerful,” was the word most often used to describe their reaction to Montoya’s images of traumatized, dead bodies. “Depressing,” was the one-word response of a 10-year-old girl at the exhibit opening. Undoubtedly, the grotesqueries of the exhibition will disturb viewers of all ages. Montoya features most of the readily identifiable forms of capital punishment used in America over the past century and a half—with the notable exceptions of the firing squad and the gas chamber. At every turn, he also provides the viewer with an eclectic, if predictable, group of texts, seemingly chosen for their stirring condemnation of capital punishment. He quotes French existentialist Albert Camus and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, both outspoken abolitionists. These and other texts make it seem as though the artist is trying to anchor his images in reasoned expressions against capital punishment. He need not have bothered. The images themselves direct the viewer to scrutinize its value, as Montoya himself concedes. In contrast to the text, the images of death “hit you somewhere else.” The lynching series delivers the first emotional punch and establishes the historical framework. Inspired by the well-known macabre postcards published as Without Sanctuary, Montoya’s lynching series is a group of images that depict a southern black man. The line of mucus or blood dribbling from the dead man’s nose forces us to see death at the end of a noose as humiliation, and reminds us that such scenes were common throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Indeed, Montoya says that as a young child he remembers hearing about Emmett Till’s notorious 1955 lynching. In recent years, a significant body of scholarship has emerged, demonstrating the existence of what some researchers refer to as “the death belt.” In this group of former Confederate states—including Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia—whites lynched people of color after Reconstruction failed in 1877. And those are precisely the states where capital punishment flourished in the mid- to -late 20th century. Montoya obviously understands this history: His images force us to focus on the noose and the expelled fluids—perhaps blood or vomit—near the face. In so doing, the artist establishes the relationship between lynching and hanging. The images of lynching and hanging are followed by several that depict electrocutions. In the late 19th century, an influential group of reformers believed that modernity—in the form of the electric chair—would make the death sentence less painful. New York state became the pioneer. Montoya shows this development in The Execution of William Kemmler and The Human Experiment, both of which memorialize the first person executed by electrocution, in 1888.

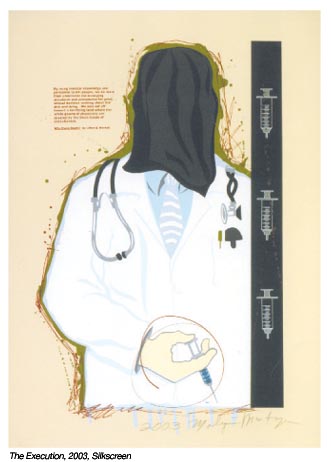

The violent subject matter of Premeditated demands a meditative space, one that allows lengthy, directed contemplation of difficult questions. Montoya begins this conversation with the viewer by asking, “Why do we kill? And what happens to us as a humanity, as a culture?” In paintings such as The Execution of the Innocent or The Execution of the Mentally Retarded, the viewer is asked to consider the moral implications of state power, a question that resonates strongly in a state that is the epicenter of America’s modern death penalty experience. Montoya’s death penalty art derives edgy rawness from his belief that “revenge doesn’t bring anything.” But revenge does make for emotionally disturbing art, as is apparent from the observations of visitors to the Dougherty Arts Center. “Powerful,” was the word most often used to describe their reaction to Montoya’s images of traumatized, dead bodies. “Depressing,” was the one-word response of a 10-year-old girl at the exhibit opening. Undoubtedly, the grotesqueries of the exhibition will disturb viewers of all ages. Montoya features most of the readily identifiable forms of capital punishment used in America over the past century and a half—with the notable exceptions of the firing squad and the gas chamber. At every turn, he also provides the viewer with an eclectic, if predictable, group of texts, seemingly chosen for their stirring condemnation of capital punishment. He quotes French existentialist Albert Camus and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, both outspoken abolitionists. These and other texts make it seem as though the artist is trying to anchor his images in reasoned expressions against capital punishment. He need not have bothered. The images themselves direct the viewer to scrutinize its value, as Montoya himself concedes. In contrast to the text, the images of death “hit you somewhere else.” The lynching series delivers the first emotional punch and establishes the historical framework. Inspired by the well-known macabre postcards published as Without Sanctuary, Montoya’s lynching series is a group of images that depict a southern black man. The line of mucus or blood dribbling from the dead man’s nose forces us to see death at the end of a noose as humiliation, and reminds us that such scenes were common throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Indeed, Montoya says that as a young child he remembers hearing about Emmett Till’s notorious 1955 lynching. In recent years, a significant body of scholarship has emerged, demonstrating the existence of what some researchers refer to as “the death belt.” In this group of former Confederate states—including Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia—whites lynched people of color after Reconstruction failed in 1877. And those are precisely the states where capital punishment flourished in the mid- to -late 20th century. Montoya obviously understands this history: His images force us to focus on the noose and the expelled fluids—perhaps blood or vomit—near the face. In so doing, the artist establishes the relationship between lynching and hanging. The images of lynching and hanging are followed by several that depict electrocutions. In the late 19th century, an influential group of reformers believed that modernity—in the form of the electric chair—would make the death sentence less painful. New York state became the pioneer. Montoya shows this development in The Execution of William Kemmler and The Human Experiment, both of which memorialize the first person executed by electrocution, in 1888.  The horror of the act has less to do with grotesque images, because—in contrast to lynching and hanging—authorities often covered the head of the person to be electrocuted. But with his depiction of the restrained body, the contorted fingers, and—particularly in Ruth Snyder, first woman executed—the seeming passivity of the condemned, Montoya provokes us just the same. He makes it difficult to imagine how anyone could have considered electrocution a less traumatic form of death. Moreover, he informs us in the accompanying text, that an eyewitness described how electrocution cooked Kemmler’s flesh while a team of doctors looked on in horror. In Botched Execution, Montoya reminds us that Florida continued to use the electric chair through the 1990s. Even before the overdue retirement of the electric chair, Texas began to tout lethal injections as another modern and purportedly less painful form of execution. A More Gentle Way of Killing (which appears on the cover of this issue of the Observer) depicts this argument. But the stylized juxtaposition of Christ’s head on the body of the condemned man is Montoya’s way of telling us that lethal injection and crucifixion share the same purpose—killing. Even in The Gentle Sleep, when Montoya uses natural representation of a person’s head to depict lethal injection, he unnerves. Although the condemned man looks peaceful, the accompanying text describes the “death rattle,” the expulsion of air forced out the windpipe as the chemical Pavulon renders the diaphragm useless, leading to suffocation. The role of medical science in the process of capital punishment has grown over time. In the Texas death house, medical technicians insert the IVs, then administer the lethal drugs from behind a one-way mirror. A doctor enters only to pronounce the time of death. In The Executioner Montoya portrays the dual role of medical science: A figure of a physician, syringe in hand, wears the executioner’s black hood. Montoya also plays with the traditional image of doctors as life’s guardians. Here, they are also the gatekeepers of death. Today, of course, the black hood takes on still another connotation, one of global infamy—the hooded prisoners of Abu Ghraib.

The horror of the act has less to do with grotesque images, because—in contrast to lynching and hanging—authorities often covered the head of the person to be electrocuted. But with his depiction of the restrained body, the contorted fingers, and—particularly in Ruth Snyder, first woman executed—the seeming passivity of the condemned, Montoya provokes us just the same. He makes it difficult to imagine how anyone could have considered electrocution a less traumatic form of death. Moreover, he informs us in the accompanying text, that an eyewitness described how electrocution cooked Kemmler’s flesh while a team of doctors looked on in horror. In Botched Execution, Montoya reminds us that Florida continued to use the electric chair through the 1990s. Even before the overdue retirement of the electric chair, Texas began to tout lethal injections as another modern and purportedly less painful form of execution. A More Gentle Way of Killing (which appears on the cover of this issue of the Observer) depicts this argument. But the stylized juxtaposition of Christ’s head on the body of the condemned man is Montoya’s way of telling us that lethal injection and crucifixion share the same purpose—killing. Even in The Gentle Sleep, when Montoya uses natural representation of a person’s head to depict lethal injection, he unnerves. Although the condemned man looks peaceful, the accompanying text describes the “death rattle,” the expulsion of air forced out the windpipe as the chemical Pavulon renders the diaphragm useless, leading to suffocation. The role of medical science in the process of capital punishment has grown over time. In the Texas death house, medical technicians insert the IVs, then administer the lethal drugs from behind a one-way mirror. A doctor enters only to pronounce the time of death. In The Executioner Montoya portrays the dual role of medical science: A figure of a physician, syringe in hand, wears the executioner’s black hood. Montoya also plays with the traditional image of doctors as life’s guardians. Here, they are also the gatekeepers of death. Today, of course, the black hood takes on still another connotation, one of global infamy—the hooded prisoners of Abu Ghraib. ![]() n his latest exhibit, Montoya has created an iconography of U.S. executions. In so doing he places our present within the framework of a horrific past, from which we are not so far removed. The images provoke. But are they all that surprising? In Premeditated, Montoya unwittingly reveals that anti-death penalty politics is at something of an impasse. The images he has chosen form part of an identifiable tradition that decries state killing. But will art and overt condemnation sway those who continue to believe in the appropriateness of capital punishment to avenge the victims of violent crimes? Montoya tries to break this deadlock with a piece called The Victim. The victim does not refer to a crime victim, but to the collateral damage created by an uncaring society that kills to avenge violent crimes. He wanted the exhibit to culminate with that piece, he told me, “to somehow show how grotesque we become when we kill. ” In his view, we are all victims of capital punishment.

n his latest exhibit, Montoya has created an iconography of U.S. executions. In so doing he places our present within the framework of a horrific past, from which we are not so far removed. The images provoke. But are they all that surprising? In Premeditated, Montoya unwittingly reveals that anti-death penalty politics is at something of an impasse. The images he has chosen form part of an identifiable tradition that decries state killing. But will art and overt condemnation sway those who continue to believe in the appropriateness of capital punishment to avenge the victims of violent crimes? Montoya tries to break this deadlock with a piece called The Victim. The victim does not refer to a crime victim, but to the collateral damage created by an uncaring society that kills to avenge violent crimes. He wanted the exhibit to culminate with that piece, he told me, “to somehow show how grotesque we become when we kill. ” In his view, we are all victims of capital punishment.  Premeditated may have begun with the former governor of Texas and the so-called “death belt,” but it does not end there. After a three-year hiatus, executions resumed in California last month when Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger denied clemency to Michael Beardslee. Now Connecticut is contemplating its first execution in 40 years. Still, Montoya is not deterred. “Just looking at these images of the death penalty reminds you of what kind of world we live in,” he told me. “And how much work we have to do to change those things. In a way they energize me, through anger, through a feeling of the injustices that we have to work against. It’s a motive, and that motive keeps me going.” Former Observer intern Patrick Timmons received his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin last May and now teaches history at a college in Georgia. He witnessed the execution of Jessie Joe Patrick in Huntsville on September 17, 2002. _______________________________________________________________

Premeditated may have begun with the former governor of Texas and the so-called “death belt,” but it does not end there. After a three-year hiatus, executions resumed in California last month when Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger denied clemency to Michael Beardslee. Now Connecticut is contemplating its first execution in 40 years. Still, Montoya is not deterred. “Just looking at these images of the death penalty reminds you of what kind of world we live in,” he told me. “And how much work we have to do to change those things. In a way they energize me, through anger, through a feeling of the injustices that we have to work against. It’s a motive, and that motive keeps me going.” Former Observer intern Patrick Timmons received his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin last May and now teaches history at a college in Georgia. He witnessed the execution of Jessie Joe Patrick in Huntsville on September 17, 2002. _______________________________________________________________

EXECUTION DIARY | BY DAVID THEIS ![]() ontemplating the photographs in Diary of an Execution, an exhibit by Swiss photojournalist Fabian Biasio, is a humbling and harrowing experience. The exhibit is currently on display at Houston’s ArtCar Museum, one of James and Ann Harithas’ art spaces. You have to pass through some almost giddy examples of car art to get to Biasio’s photographs, so stepping into the room set aside for Diary is like leaving a rowdy street to enter a quiet chapel. The exhibition documents the days leading up to the 2003 execution of James Colburn, whom the state of Texas put to death despite protests from many quarters. Colburn was mentally ill—paranoid schizophrenic—which the state didn’t even attempt to deny. Colburn was simply judged to have failed the right/wrong test. Schizophrenic or not, he knew that he did wrong when he killed 55-year-old Peggy Murphy in his hometown of Conroe. Indeed, according to the facsimile of the arrest report on display, he raped and killed Murphy, then asked her neighbors to call the police. The report states, “He killed the woman because he wanted to return to prison.” The exhibition doesn’t go into great detail concerning Colburn’s mental health. He only appears in a few images, in fact. Instead the heart-breaking show gives us pictures of his sister, Tina Morris, in the days leading up to his execution and immediately after. Biasio seems to have had complete access to Morris’ grief, as she breaks down again and again in front of his camera. The photos tell a very powerful story, some through the use of homey and ironic detail, such as the photo of Tina buying plastic flowers for her still-living brother’s upcoming funeral. But some are simply overpowering, even if you try to look at them from an aesthetic point of view. There’s the quartet of photos showing Tina swigging on some kind of bottle, then breaking down in the Polunsky Unit parking lot before going in to see her brother. The caption for a photo taken 24 hours before the execution tells us that she “vomited all day.” We see her calling family members to coordinate their last trip to Polunsky. The next morning, Tina’s boyfriend, just off the night shift, picks up Tina in his pickup to drive her to Huntsville. Biasio takes a matter-of-fact shot of the road, allowing us to see the last stretch of highway upon which James Colburn will ever gaze. Once at Huntsville, the family members kill time by putting together a puzzle in the macabrely named “Christian Hospitality House.” A minister comes in to lead them in a group prayer, and Tina’s cheeks puff out in pain as she tries to pray along. At 5 p.m. she makes her last phone call, and at 5:30 she and her relatives finally make their way to the Walls Unit. At 6 p.m.—execution time—we see a small crowd of protestors, one holding a “Treat the Mentally Ill” poster. At 6:21 James Colburn is dead. “I have no one to blame but myself,” he said. At 6:30 we see the removal of his “personal items,” a plastic bag full of empty soda cans. Then comes the image of Tina stroking her dead brother’s cheek. “For the first time in 10 years,” the caption reads, “Tina can touch her brother.” Three days later, James is buried in the family’s Corsicana plot. There’s not much to say about the photographer’s art, other than to say that by documenting the hour-by-hour passage of time, Biasio succeeds in making the somehow abstract notion of execution quite real, and, I would think, shameful to us as Texans and Americans. Of course, shame is in short supply these days. A footnote: On January 20, Dave Atwood of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, one of the exhibition’s principal organizers, was sentenced to five days in prison for crossing the yellow protest line at Huntsville during an execution last November. Diary of an Execution is on view at Houston’s ArtCar Museum through March.

ontemplating the photographs in Diary of an Execution, an exhibit by Swiss photojournalist Fabian Biasio, is a humbling and harrowing experience. The exhibit is currently on display at Houston’s ArtCar Museum, one of James and Ann Harithas’ art spaces. You have to pass through some almost giddy examples of car art to get to Biasio’s photographs, so stepping into the room set aside for Diary is like leaving a rowdy street to enter a quiet chapel. The exhibition documents the days leading up to the 2003 execution of James Colburn, whom the state of Texas put to death despite protests from many quarters. Colburn was mentally ill—paranoid schizophrenic—which the state didn’t even attempt to deny. Colburn was simply judged to have failed the right/wrong test. Schizophrenic or not, he knew that he did wrong when he killed 55-year-old Peggy Murphy in his hometown of Conroe. Indeed, according to the facsimile of the arrest report on display, he raped and killed Murphy, then asked her neighbors to call the police. The report states, “He killed the woman because he wanted to return to prison.” The exhibition doesn’t go into great detail concerning Colburn’s mental health. He only appears in a few images, in fact. Instead the heart-breaking show gives us pictures of his sister, Tina Morris, in the days leading up to his execution and immediately after. Biasio seems to have had complete access to Morris’ grief, as she breaks down again and again in front of his camera. The photos tell a very powerful story, some through the use of homey and ironic detail, such as the photo of Tina buying plastic flowers for her still-living brother’s upcoming funeral. But some are simply overpowering, even if you try to look at them from an aesthetic point of view. There’s the quartet of photos showing Tina swigging on some kind of bottle, then breaking down in the Polunsky Unit parking lot before going in to see her brother. The caption for a photo taken 24 hours before the execution tells us that she “vomited all day.” We see her calling family members to coordinate their last trip to Polunsky. The next morning, Tina’s boyfriend, just off the night shift, picks up Tina in his pickup to drive her to Huntsville. Biasio takes a matter-of-fact shot of the road, allowing us to see the last stretch of highway upon which James Colburn will ever gaze. Once at Huntsville, the family members kill time by putting together a puzzle in the macabrely named “Christian Hospitality House.” A minister comes in to lead them in a group prayer, and Tina’s cheeks puff out in pain as she tries to pray along. At 5 p.m. she makes her last phone call, and at 5:30 she and her relatives finally make their way to the Walls Unit. At 6 p.m.—execution time—we see a small crowd of protestors, one holding a “Treat the Mentally Ill” poster. At 6:21 James Colburn is dead. “I have no one to blame but myself,” he said. At 6:30 we see the removal of his “personal items,” a plastic bag full of empty soda cans. Then comes the image of Tina stroking her dead brother’s cheek. “For the first time in 10 years,” the caption reads, “Tina can touch her brother.” Three days later, James is buried in the family’s Corsicana plot. There’s not much to say about the photographer’s art, other than to say that by documenting the hour-by-hour passage of time, Biasio succeeds in making the somehow abstract notion of execution quite real, and, I would think, shameful to us as Texans and Americans. Of course, shame is in short supply these days. A footnote: On January 20, Dave Atwood of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, one of the exhibition’s principal organizers, was sentenced to five days in prison for crossing the yellow protest line at Huntsville during an execution last November. Diary of an Execution is on view at Houston’s ArtCar Museum through March.