Thinking Outside the Texas Box

How Other States Handle Some of the Problems Facing Texas

Thinking Outside the Texas Box

How other states deal with some of the problems facing Texas

BY PAUL SWEENEY

![]() an Texas learn from other states? Sure it can. After all, businesses learn from each other all the time. They call it adopting “best practices.” So why can’t Texas government take a page out of the corporate playbook, consider what “best practices” are occurring elsewhere, and apply those lessons here at home? Consider the conundrum of education funding. Largely because of a rickety school finance system, Texas’ population is mired in a condition approaching, if not outright ignorance, at least second-class educational status. According to recent figures compiled by Sen. Eliot Shapleigh (D-El Paso), the Lone Star State ranks 46th among the 50 states in the percentage of its adult population with high school diplomas. Texas is in 50th place—dead last—in high school completion rates. As the Texas Legislature convenes, moreover, the state is under a court order to revamp its system of school funding, which has been declared unconstitutional. Texas is not alone in short-changing its schools, of course. But one state that is doing a better job than most in confronting the difficult task of paying for its children’s education is Illinois, which faces many of the same issues that vex Texas, such as a huge influx of immigrants who do not speak English at home. In addition to school finance, the Observer decided to look at how other states are responding to several issues that are—or ought to be—on the Legislature’s radar screen: the minimum wage, payday loans, and publicly financed elections. Clearly this is not an exhaustive list. It leaves out numerous critical issues such as child protective services and children’s health care. There is no shortage of worthy efforts among the other 49 states to improve public safety and reform prison systems, modernize mass transportation and reverse environmental degradation—particularly in the areas of ozone air pollution and toxic hazardous waste emissions. As the session unfolds, the Observer hopes to revisit the land of best practices with its bounty of workable solutions for Texas. SCHOOL FINANCE When it comes to financing its schools—indeed when it comes to finding revenues to support state government and public services—Texas is in a fix. The optimum solution is the one that can’t be contemplated. On January 10, the Texas comptroller announced that the state will have $64.7 billion in general revenue available for the next two years, about $7 billion short of what is needed to maintain current programs and restore services cut during the last session, according to the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a non-profit think tank in Austin.

an Texas learn from other states? Sure it can. After all, businesses learn from each other all the time. They call it adopting “best practices.” So why can’t Texas government take a page out of the corporate playbook, consider what “best practices” are occurring elsewhere, and apply those lessons here at home? Consider the conundrum of education funding. Largely because of a rickety school finance system, Texas’ population is mired in a condition approaching, if not outright ignorance, at least second-class educational status. According to recent figures compiled by Sen. Eliot Shapleigh (D-El Paso), the Lone Star State ranks 46th among the 50 states in the percentage of its adult population with high school diplomas. Texas is in 50th place—dead last—in high school completion rates. As the Texas Legislature convenes, moreover, the state is under a court order to revamp its system of school funding, which has been declared unconstitutional. Texas is not alone in short-changing its schools, of course. But one state that is doing a better job than most in confronting the difficult task of paying for its children’s education is Illinois, which faces many of the same issues that vex Texas, such as a huge influx of immigrants who do not speak English at home. In addition to school finance, the Observer decided to look at how other states are responding to several issues that are—or ought to be—on the Legislature’s radar screen: the minimum wage, payday loans, and publicly financed elections. Clearly this is not an exhaustive list. It leaves out numerous critical issues such as child protective services and children’s health care. There is no shortage of worthy efforts among the other 49 states to improve public safety and reform prison systems, modernize mass transportation and reverse environmental degradation—particularly in the areas of ozone air pollution and toxic hazardous waste emissions. As the session unfolds, the Observer hopes to revisit the land of best practices with its bounty of workable solutions for Texas. SCHOOL FINANCE When it comes to financing its schools—indeed when it comes to finding revenues to support state government and public services—Texas is in a fix. The optimum solution is the one that can’t be contemplated. On January 10, the Texas comptroller announced that the state will have $64.7 billion in general revenue available for the next two years, about $7 billion short of what is needed to maintain current programs and restore services cut during the last session, according to the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a non-profit think tank in Austin.  Much of the new funding will be earmarked to support the public schools. In the 2003-2004 school year, Texas spent just $7,891 per pupil in kindergarten through 12th grade (K-12), according to the CPPP, nearly $900 less than the national average. Texans are not only displeased that their children receive substandard education but they are grumping about the way the state pays for its increasingly inferior schools. Essentially the current system of school finance, in what is known popularly as a Robin Hood formula, shifts money from the property taxes collected in richer school districts to the poorer ones. That helps equalize education funding and, it is true, the majority of school districts benefit. Nonetheless, a state district judge in Travis County has given the Legislature an ultimatum: Institute a proper funding mechanism by next autumn or he’ll enjoin the state from spending money on the schools, effectively shutting them down. In addition to locating a way to provide adequate funding for the schools, Texas lawmakers must also find a way to raise $2.2 billion to reduce local property taxes for the next biennium. A proposal that is going before the Illinois state legislature this year offers a better model. A draft report issued by the Chicago-based Center for Tax and Budget Accountability—a bipartisan, non-profit organization that boasts James D. Nowlan, a former Republican legislator and candidate for lieutenant government, as its research director—contains key elements sorely missing from the current school finance system in Texas. It makes the fiscal system both fairer (meaning that those with the capacity to pay taxes are the ones who actually do) and responsive to economic growth; it generates significant revenue; and it provides property tax relief. If the Illinois center’s proposals were to be adopted, that state would raise a whopping $7.25 billion in public revenue—while providing $2.4 billion in property tax relief. But unlike Texas, which critics like Matt Gardner at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington say is “looking under the cushions for loose change,” Illinois is amenable to a state income tax. It is proposing a modest 5 percent, across-the-board income tax rate. With all due respect to the protestations of the Texas governor and the leadership of the Texas Legislature, almost every fair-minded tax expert will tell you that a state personal income tax (which can be deducted from federal income taxes) is not only necessary but desirable. “If you take the personal income tax off the table,” notes Dick Lavine, senior fiscal analyst at the CPPP, “you’re stuck with the second-best solutions.” A state income tax is not just a dependable source of revenue but it is less burdensome on persons without means than the assorted sales taxes, lotteries, alcohol and tobacco taxes, user fees, and property taxes that Texas leans on most heavily. An income tax is also more equitable. Ralph Martire, executive director at the Illinois center, notes that since 1999 the average income for the wealthiest 20 percent of the U.S. population is up by 34 percent on average while the bottom 60 percent have seen their paychecks shrink by 6 percent.

Much of the new funding will be earmarked to support the public schools. In the 2003-2004 school year, Texas spent just $7,891 per pupil in kindergarten through 12th grade (K-12), according to the CPPP, nearly $900 less than the national average. Texans are not only displeased that their children receive substandard education but they are grumping about the way the state pays for its increasingly inferior schools. Essentially the current system of school finance, in what is known popularly as a Robin Hood formula, shifts money from the property taxes collected in richer school districts to the poorer ones. That helps equalize education funding and, it is true, the majority of school districts benefit. Nonetheless, a state district judge in Travis County has given the Legislature an ultimatum: Institute a proper funding mechanism by next autumn or he’ll enjoin the state from spending money on the schools, effectively shutting them down. In addition to locating a way to provide adequate funding for the schools, Texas lawmakers must also find a way to raise $2.2 billion to reduce local property taxes for the next biennium. A proposal that is going before the Illinois state legislature this year offers a better model. A draft report issued by the Chicago-based Center for Tax and Budget Accountability—a bipartisan, non-profit organization that boasts James D. Nowlan, a former Republican legislator and candidate for lieutenant government, as its research director—contains key elements sorely missing from the current school finance system in Texas. It makes the fiscal system both fairer (meaning that those with the capacity to pay taxes are the ones who actually do) and responsive to economic growth; it generates significant revenue; and it provides property tax relief. If the Illinois center’s proposals were to be adopted, that state would raise a whopping $7.25 billion in public revenue—while providing $2.4 billion in property tax relief. But unlike Texas, which critics like Matt Gardner at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington say is “looking under the cushions for loose change,” Illinois is amenable to a state income tax. It is proposing a modest 5 percent, across-the-board income tax rate. With all due respect to the protestations of the Texas governor and the leadership of the Texas Legislature, almost every fair-minded tax expert will tell you that a state personal income tax (which can be deducted from federal income taxes) is not only necessary but desirable. “If you take the personal income tax off the table,” notes Dick Lavine, senior fiscal analyst at the CPPP, “you’re stuck with the second-best solutions.” A state income tax is not just a dependable source of revenue but it is less burdensome on persons without means than the assorted sales taxes, lotteries, alcohol and tobacco taxes, user fees, and property taxes that Texas leans on most heavily. An income tax is also more equitable. Ralph Martire, executive director at the Illinois center, notes that since 1999 the average income for the wealthiest 20 percent of the U.S. population is up by 34 percent on average while the bottom 60 percent have seen their paychecks shrink by 6 percent.  A state income tax also offers a mechanism to build more fairness into taxation. With an income tax system in place, it is possible to offer tax credits to lower-income people who may be paying too much money in regressive sales taxes. The Illinois plan, for example, includes tax credits, ensuring that the bottom 60 percent of all income earners do not pay more taxes after reforms. And the bottom 20 percent will actually realize a tax decrease. Here are the main features of the Illinois center’s proposal: • The state would raise $5 billion by increasing its across-the-board income tax to 5 percent, up from 3 percent (tying it, after the change, with Mississippi for the 7th lowest income tax rate in the country). • It raises $359 million by including the retirement income of seniors who earn annual incomes of more than $75,000—which puts them among the wealthiest 23 percent of all taxpayers. • It captures another $491 million by increasing the Corporate Income Tax to 8 percent, up from 6 percent. • It picks up $900 million in sales taxes by expanding the base to include entertainment and personal services, such as home-cleaning and maintenance. Undoubtedly, Illinois’ income tax and corporate tax proposals will frighten off a good many Texas lawmakers. Even so, one feature of the tax debate there might appeal to, if not the better angels of their nature, at least their desire for continued economic prosperity in the information age.

A state income tax also offers a mechanism to build more fairness into taxation. With an income tax system in place, it is possible to offer tax credits to lower-income people who may be paying too much money in regressive sales taxes. The Illinois plan, for example, includes tax credits, ensuring that the bottom 60 percent of all income earners do not pay more taxes after reforms. And the bottom 20 percent will actually realize a tax decrease. Here are the main features of the Illinois center’s proposal: • The state would raise $5 billion by increasing its across-the-board income tax to 5 percent, up from 3 percent (tying it, after the change, with Mississippi for the 7th lowest income tax rate in the country). • It raises $359 million by including the retirement income of seniors who earn annual incomes of more than $75,000—which puts them among the wealthiest 23 percent of all taxpayers. • It captures another $491 million by increasing the Corporate Income Tax to 8 percent, up from 6 percent. • It picks up $900 million in sales taxes by expanding the base to include entertainment and personal services, such as home-cleaning and maintenance. Undoubtedly, Illinois’ income tax and corporate tax proposals will frighten off a good many Texas lawmakers. Even so, one feature of the tax debate there might appeal to, if not the better angels of their nature, at least their desire for continued economic prosperity in the information age.

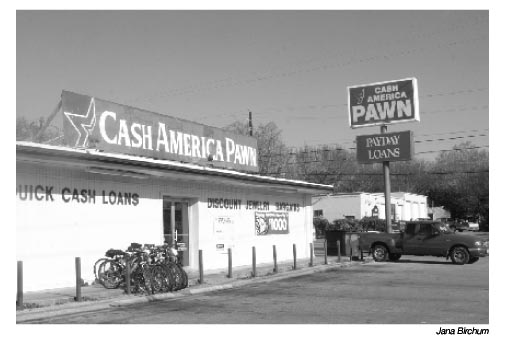

“Constraining resources for schools does not just hurt Illinois children,” the center’s report declares, “but also negatively impacts the state’s ability to attract and maintain business. According to a recent report by the Illinois Chamber of Commerce, improving public education is one of the most effective economic development tools available to the state.” MINIMUM WAGE Here’s a no-brainer for Texas legislators. To promote economic development, save the taxpayers money, and help lift a half-million of the state’s poorest workers out of poverty, why not do what 14 other states have done and raise the minimum wage? At present, the minimum wage in Texas is the same as the federal government’s rate—a laughably meager $5.15-an-hour—which has not been increased since 1997. But it’s a cruel joke at the expense of 500,000 Texas workers, whose annual take of $10,712 does not leave much over after paying $470-a-month for the average one-bedroom in Houston. While it is commonly assumed that unskilled teenagers working an after-school job constitute the bulk of the workers earning the minimum wage, only about one in five low-wage workers is under 20 years old, reports Don Baylor, a policy analyst at CPPP. That means that 80 percent of low-wage employees are actually adults 20 or older. “For the most part, they work at retail trade and service jobs—as cashiers in convenience stores and flipping burgers,” Baylor says. “Or they serve as maids at motels and working presses at laundry jobs. Maybe they’re a waitress or busboy at a local diner where there isn’t much tipping.”  The two states with the highest minimum wage are located in the Northwest: Washington state with $7.16 and Alaska with $7.15. The most recent state to raise the minimum wage legislatively was New York state, where both houses—including a Republican-controlled state Senate—combined to override a gubernatorial veto over the summer. On January 1, 2005, the minimum wage in New York rose to $6.00-an-hour, in the first stage of a process that will bring up the state minimum wage to $7.15 by 2007. In addition, the voters in two Red States—Nevada and Florida—opted by overwhelming margins in plebiscites—71 to 29 percent of the vote in Nevada and 68 to 32 percent in Florida—to raise the minimum wage. “It wasn’t even close,” says Bernie Horn, policy analyst at the Center for Policy Alternatives in Washington, D.C., referring to the plebiscites in both states. Noting that the last time that voters rejected a hike in the minimum wage was in Missouri in 1996, he adds: “Everyone gets what it means to raise the minimum wage. It’s not complicated.” One concern likely to be aired—most likely by lobbyists for small businesses—is that a minimum wage hike will prove unduly painful to labor-intensive, mom-and-pop concerns. This is known as “the dis-employment thesis.” Yet, as the President’s Council of Economic Advisers annual report to Congress found in 1999: “Many different studies have examined this issue [the dis-employment thesis] and the weight of the evidence suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage have had very little or no effect on employment.” Add to that an April 2004 study by the non-profit Fiscal Policy Institute in New York, which found that “the number of employees in small establishments grew by 4.8 percent between 1998 and 2001” in the 10 states and the District of Columbia with higher minimum wage rates at the time—“nearly twice the 1.6 percent growth pace in the other states.” For Texas legislators fretting about the rising costs of public services, a higher state minimum wage would provide serendipitous benefits. Less state money would be necessary to subsidize housing, Medicaid, and other public services for the working poor. At the same time, with more money in their pockets, wage earners are likely to inject added cash into local economies. And that also means more sales tax dollars would flow into the coffers of state government. Moreover, a rise in the minimum wage benefits a broader class of low-wage workers than just those locked in the cellar of the economy, notes CPPP’s Baylor. “There is a band of people at the lowest end of the low-wage workforce” who would gain from such a wage increase, he says. “If you raised the minimum wage to six dollars an hour, it would probably help everyone now making less than seven dollars an hour.” PAYDAY LOANS During the current session of the Texas Legislature, chances are good that a well-groomed, engaging representative from the payday loan industry will pay a visit to the offices of Texas’ most influential lawmakers, strike up companionate conversation, and ask to be regulated. But a state official in Georgia, who asked not to be identified by name, warns that the industry is not to be trusted. “You can’t regulate them,” the Georgia official says. “It’s a trick loan. Trying to regulate them is like trying to domesticate a wolf.” Led by companies such as Cash America and Advance America, much of the payday loan industry is from out-of-state. But it has a trade association with such a friendly name—the Community Financial Services Association (CFSA)—that its legislative representatives will seem down-home, even neighborly. The industry’s lobbyists will distribute a handsome brochure, the “Payday Advance Customer Satisfaction Survey,” which paints a benign view of the industry. The brochure promises an objective survey of 2,000 payday loan customers conducted for CFSA by the Cypress Research Group of Shaker Heights, Ohio, and it provides lawmakers with fabulous information about the industry. For example, when queried whether they “treated customers fairly” or were a “good community citizen,” the industry scored a 65 percent “favorability” rating, making it second only to grocery stores, which had an 81 percent “favorability” rating, and ahead of credit unions, fast-food restaurants, and banks. But in 2004, Georgia’s state legislature cast a jaundiced eye on the payday loan industry. In putting the payday lenders out of business, the Peach State joined 13 others that essentially outlaw their operations. Georgia’s legislation, moreover, includes harsh penalties that provide for prosecution for industry lawbreakers under racketeering laws—up to 20 years’ imprisonment, a maximum fine of $25,000 per violation, and allowance for class-action lawsuits. Payday loans are a new name for what was known in the 19th century as “salary buying” or “wage buying” and was largely outlawed during the Depression. Basically, the borrower takes out a loan under $500—the average loan is about $300, says Gail Hillebrand, an attorney with Consumers Union in San Francisco—and writes a check for the borrowed money which won’t be cashed for two weeks, plus the fee of $15.00 per hundred dollars. “The concept of the loan is that it won’t be cashed until payday,” says Hillebrand. “But as a practical matter, the loan doesn’t usually doesn’t get paid back. Every two weeks they’ll urge you to roll over the loan.” According to one recent study of borrowers in Indiana, she says, the average borrower interviewed by researchers reported rolling over his or her loan 11 times. The result: Such “loan flipping” results in the borrower’s typically paying $533.50 over 22 weeks, notes Hillebrand, “and they still haven’t repaid a dime on th

The two states with the highest minimum wage are located in the Northwest: Washington state with $7.16 and Alaska with $7.15. The most recent state to raise the minimum wage legislatively was New York state, where both houses—including a Republican-controlled state Senate—combined to override a gubernatorial veto over the summer. On January 1, 2005, the minimum wage in New York rose to $6.00-an-hour, in the first stage of a process that will bring up the state minimum wage to $7.15 by 2007. In addition, the voters in two Red States—Nevada and Florida—opted by overwhelming margins in plebiscites—71 to 29 percent of the vote in Nevada and 68 to 32 percent in Florida—to raise the minimum wage. “It wasn’t even close,” says Bernie Horn, policy analyst at the Center for Policy Alternatives in Washington, D.C., referring to the plebiscites in both states. Noting that the last time that voters rejected a hike in the minimum wage was in Missouri in 1996, he adds: “Everyone gets what it means to raise the minimum wage. It’s not complicated.” One concern likely to be aired—most likely by lobbyists for small businesses—is that a minimum wage hike will prove unduly painful to labor-intensive, mom-and-pop concerns. This is known as “the dis-employment thesis.” Yet, as the President’s Council of Economic Advisers annual report to Congress found in 1999: “Many different studies have examined this issue [the dis-employment thesis] and the weight of the evidence suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage have had very little or no effect on employment.” Add to that an April 2004 study by the non-profit Fiscal Policy Institute in New York, which found that “the number of employees in small establishments grew by 4.8 percent between 1998 and 2001” in the 10 states and the District of Columbia with higher minimum wage rates at the time—“nearly twice the 1.6 percent growth pace in the other states.” For Texas legislators fretting about the rising costs of public services, a higher state minimum wage would provide serendipitous benefits. Less state money would be necessary to subsidize housing, Medicaid, and other public services for the working poor. At the same time, with more money in their pockets, wage earners are likely to inject added cash into local economies. And that also means more sales tax dollars would flow into the coffers of state government. Moreover, a rise in the minimum wage benefits a broader class of low-wage workers than just those locked in the cellar of the economy, notes CPPP’s Baylor. “There is a band of people at the lowest end of the low-wage workforce” who would gain from such a wage increase, he says. “If you raised the minimum wage to six dollars an hour, it would probably help everyone now making less than seven dollars an hour.” PAYDAY LOANS During the current session of the Texas Legislature, chances are good that a well-groomed, engaging representative from the payday loan industry will pay a visit to the offices of Texas’ most influential lawmakers, strike up companionate conversation, and ask to be regulated. But a state official in Georgia, who asked not to be identified by name, warns that the industry is not to be trusted. “You can’t regulate them,” the Georgia official says. “It’s a trick loan. Trying to regulate them is like trying to domesticate a wolf.” Led by companies such as Cash America and Advance America, much of the payday loan industry is from out-of-state. But it has a trade association with such a friendly name—the Community Financial Services Association (CFSA)—that its legislative representatives will seem down-home, even neighborly. The industry’s lobbyists will distribute a handsome brochure, the “Payday Advance Customer Satisfaction Survey,” which paints a benign view of the industry. The brochure promises an objective survey of 2,000 payday loan customers conducted for CFSA by the Cypress Research Group of Shaker Heights, Ohio, and it provides lawmakers with fabulous information about the industry. For example, when queried whether they “treated customers fairly” or were a “good community citizen,” the industry scored a 65 percent “favorability” rating, making it second only to grocery stores, which had an 81 percent “favorability” rating, and ahead of credit unions, fast-food restaurants, and banks. But in 2004, Georgia’s state legislature cast a jaundiced eye on the payday loan industry. In putting the payday lenders out of business, the Peach State joined 13 others that essentially outlaw their operations. Georgia’s legislation, moreover, includes harsh penalties that provide for prosecution for industry lawbreakers under racketeering laws—up to 20 years’ imprisonment, a maximum fine of $25,000 per violation, and allowance for class-action lawsuits. Payday loans are a new name for what was known in the 19th century as “salary buying” or “wage buying” and was largely outlawed during the Depression. Basically, the borrower takes out a loan under $500—the average loan is about $300, says Gail Hillebrand, an attorney with Consumers Union in San Francisco—and writes a check for the borrowed money which won’t be cashed for two weeks, plus the fee of $15.00 per hundred dollars. “The concept of the loan is that it won’t be cashed until payday,” says Hillebrand. “But as a practical matter, the loan doesn’t usually doesn’t get paid back. Every two weeks they’ll urge you to roll over the loan.” According to one recent study of borrowers in Indiana, she says, the average borrower interviewed by researchers reported rolling over his or her loan 11 times. The result: Such “loan flipping” results in the borrower’s typically paying $533.50 over 22 weeks, notes Hillebrand, “and they still haven’t repaid a dime on th

principal.” Adds the Georgia state official abou

such egregious practices: “We saw cases of the guy who’s borrowed $500, pays back $3,000, and yet still owes the $500. And since they’ve got your check, there are very few defaults.” (Cash America only allows four rollovers before they send the loan to the collection process, insists a spokeswoman.) In Texas, the payday loan industry relies on federal banking laws that prevent states from regulating the interest rates of out-of-state banks. One result of the deregulation mania that has characterized the banking industry over the last three decades is that states are prohibited from regulating the “exported interest rates” charged by out-of-state banks headquartered outside their territorial boundaries (one reason why the bank issuing your Visa or Mastercard is likely to have an address in the permissive states of Delaware or South Dakota, where usury laws do not exist). Thus, while states can regulate the interest rates charged by payday lenders, they say their hands are tied if the payday lenders act as agents for out-of-state banks. Critics of the industry call this scheme a “rent-a-bank” arrangement and contend that it is largely a ruse aimed at circumventing state laws. The practical result is that payday lenders can charge annual rates of more than 569.99 percent for a $100 loan, more than double the ceiling of 240 percent imposed on in-state lenders, according to a fee chart released by Sen. Shapleigh’s office. Although they arrived in the state just five years ago, the out-of-state payday lenders dramatically outstrip their Texas brethren in both the number of unregulated loans and in dollar amounts. According to testimony to a Senate committee from the Office of Consumer Credit Commissioner, payday loans carrying “exported rates” accounted for roughly 1.81 million loans amounting to $612 million. That compares with the far fewer loans at lesser dollar amounts by in-state payday lenders: just 100,000 regulated loans totaling $14 million, reports the OCCC. Along with getting their Texas customers in hock up to their eyeballs, the industry siphons money away from local economies often to distant, out-of-state cities. For its part, the state of Georgia did not attempt to regulate interest rates. Instead, its legislation took aim at the “rent-a-bank” arrangement, in which the payday lenders typically earn 80 percent or more per loan, paying banks 10 percent to 20 percent of its cut. The Georgia legislation requires the agents of an out-of-state bank to earn no more than 50 percent of the loan payments. The Georgia attorney general’s office faced down 29 lawyers from several major law firms who have sought to have the courts void the law. But neither the courts nor federal banking authorities have found fault with the legislation. Says the Georgia state official, “So far it’s worked.” PUBLIC FINANCING Texas legislators could do worse than to look to the states of Arizona, New Mexico, Maine, and North Carolina for “best practices” in running clean elections. Those states have instituted public financing programs that make it increasingly possible for candidates to run for office and win election without taking money from the usual suspects: the political action committees formed by banks, utilities, petrochemical companies, realtors, Big Insurance, homebuilders, highway contractors, liquor distillers. After the election, of course, these interests can be found in the hallways of the Texas Capitol looking for watered-down environmental and consumer regulations, generous subsidies, highway and government contracts, and other favorable legislation. Because of their economic might, even the politician inclined to challenge them must think twice. “For a legislator in a competitive district it’s hard to oppose legislation if you think they’ll give $250,000 to your opponent during the next election,” says Fred Lewis with Campaigns For People. “The current system disenfranchises people.” Compare that to Arizona, which may be the country’s leader in clean elections. Thanks to the 1998 legislation that provided for public financing of election, Arizona governor Janet Napolitano was able to raise $3 million in public funds in 2002 and defeat an opponent who was funded by millions in special-interest money. In addition, 10 of 11 statewide offices are held by publicly financed candidates—including the state’s attorney general, treasurer, and all five Republican members of the Corporations Commission, which regulates the state’s utility industry. Moreover, 35 of 60 members of the Arizona state House ran “clean” as did 7 members of the Senate. The Arizona system is funded with a 10-percent surcharge on civil and criminal penalties, a $5 check-off on the state income taxes, and personal donations of up to $500. Nick Nyhart, the executive director of Public Campaign in Washington, D.C., calls Arizona and Maine—where 83 percent of the state Senate and 77 percent of the House ran with public financing—“a shining model for comprehensive reform for the rest of the nation.” Back in Austin, however, Lewis warns that Texans have much ground work to do before we contemplate publicly financed elections. This session, for example, there will be battles over whether to tighten—or gut—the limits on corporate and labor union campaign donations. “To me the ultimate system would have an independent redistricting commission and public financing of campaigns,” he says. “But we need to get these other pieces in place first.” Paul Sweeney, a freelance writer living in Austin, is a longtime Observer contributor. He has worked at Texas newspapers in Corpus Christi and El Paso and has written for The Boston Globe, The New York Times and Business Week.