Out of Africa and Into Texas

by Steven G. Kellman

When Peter Kon Dut and Santino Majok Chuor were orphaned by Arab intruders from the north of Sudan, they were forced to grow up quickly and never lost the haunting memory of early, violent deprivation.

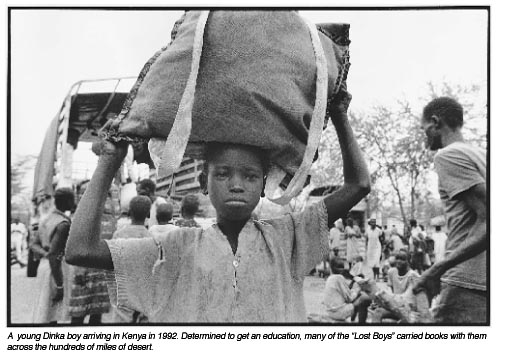

Peter was only four when raiders attacked his village and killed his parents. He was 17 when he first drove a car on a Texas freeway. Peter and Santino are among 20,000 boys from Dinka and other tribes uprooted by pogroms in western and southern Sudan. Those who managed to survive armed marauders, hungry lions, and other hazards of a long and arduous transnational journey found shelter in a refugee camp in Kenya. In 2001, 4,000 of these “Lost Boys of Sudan” were promised a free education and transported to the United States. They vowed to return to Africa better equipped to assist their fellow refugees.

“I will not forget our Dinka culture,” insists Peter. “It is important that I help my friends,” says Santino before departing for what he calls “a land called Houston.” Sudan is a land even larger than Texas, one-fourth as large as the entire United States. In Lost Boys of Sudan, filmmakers Megan Mylan and John Shenk follow those two young men, from their flight out of Africa through their first 14 months in the United States. After a national theatrical run during the summer, the film is scheduled to be broadcast as part of the PBS nonfiction feature series “P.O.V.” on Tuesday, September 28. It is “reality TV” in which survival is not just a programming gimmick.

While editing their footage down to 87 minutes, Mylan and Shenk record the experiences of Peter and Santino without voiceovers or any other overt intrusion. We accompany the refugees on their first plane trip, during which they marvel at the aerial vistas through the window and the strange substances wrapped in plastic that a flight attendant deposits on their laps. “This journey is like you are going to heaven,” an envious refugee had assured a friend on the eve of his departure from Kenya. But the destination turns out to be less than celestial. For Sudan’s lost boys, Houston, where they arrive, is another kind of Neverland, where the novelty of cheeseburgers, deodorant sticks, and electric stoves soon grows cold. They set about studying maps and the English language. They learn that the sight of men holding hands in public means something different in Texas than it did back home. While offering a glimpse of unfamiliar faces and lives, the film defamiliarizes American customs a viewer might otherwise take for granted. A YMCA case worker introduces the Sudanese to a kitchen garbage disposal unit and a supermarket. Furniture is donated to the newcomers, and, for the first four months, benefactors pay the rent on the apartment shared by several Sudanese. Santino finds employment in a plastics factory, Peter in a machine shop. Santino is paid minimum wage and spends up to two hours a day commuting by bus to his job.

After five months, no closer to the education he seeks and was promised, Peter skips out on Houston and Santino. Most of the rest of the film crosscuts between Kansas, where Peter enrolls in Olathe East High School and works at Wal-Mart, and Houston. There Santino continues in his entry-level, assembly-line job but bears the entire burden of paying for his apartment, while also trying to send funds back to Africa. He is summoned to court for operating a vehicle without a license after failing the driving test. And, discarding the receipt for his monthly rent, because of his ignorance of the conventions of financial transactions, he finds himself dunned for a hefty sum that he already paid. Except for some African-American thugs, whose skins are lighter than theirs but whose intentions appear darker, everyone the Sudanese meets oozes with benevolence and glows with innocence. Once settled in our hospitable country, they assume, the wretched refugees from across the seas live happily ever after. Yet, distressed by a boring job, financial woes, and solitude, Santino never seems at home in Houston, or anywhere else outside of his vanished childhood in Sudan. “They called us lost boys because they found us without parents,” explains Peter, but one need not be an orphan to be lost in America. Peter and Santino have lost their boyhood, and Sudan.

More successful than Santino at Yankee individualism and at adding English to Dinka, Arabic, and Swahili in his linguistic repertoire, Peter is at best ambivalent. “I cannot say if America is good or America is bad,” he says. In his job at Wal-Mart, he is assigned to gather shopping carts in the parking lot, because his supervisor believes that Africans are best equipped for outdoor work. One of 1,500 students at Olathe East, Peter takes classes in subjects including math, music, biology, ceramics, and English as a Second Language. He often feels alienated and lonely in Kansas. It is hard for Peter to bond with male classmates over talk of girls. Though he tries but fails to make the varsity basketball team, he graduates from high school and sets his sights on college.

“Things are really hard here,” he tells his sister in a phone call back to Africa. She berates him for neglecting where and whom he came from. But the hardships of Kansas must be as unfathomable to an African as the ordeal of a Dinka refugee is to the kindly Christian lady who stops by the lost boys’ Houston apartment complex to offer her encouragement. Peter is as bewildered as many viewers will be when a pizza party at a high school classmate’s house morphs into a fervent revival meeting. The peculiar tribal customs of born-again Christians are unnerving to a stranger, whether from Sudan or the United States.

When a perky high school journalist in Kansas asks Peter to recount his grim experiences, he cannot begin to explain. An eye-opening take on the American Dream through the fate of reluctant immigrants, Lost Boys of Sudan could tell Peter’s Kansas classmate more than she might want to know about the ordeal of being assaulted, uprooted, and transported to an alien culture. When, as a gift to another classmate, he captures a wild bird and encloses it within an improvised cage, the image captures Peter, too.

One year after leaving Kenya, the lost boys of Sudan, now lanky men dispersed to San Diego, Houston, Phoenix, Boston, Chicago, Seattle, Fargo, and other cities throughout the United States, are reunited in a YMCA camp outside Washington, D.C. Canoeing, swimming, singing, and dancing, they rejoice in their good fortune. Yet, as one observes: “It’s clear there’s no heaven on earth.” There were more than 4,000 stories in Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp when Mylan and Shenk visited it. The two that they happened to focus on, Peter Kon Dut and Santino Majok Chuor, may or may not be synecdoches, parts that stand for a blighted whole. Thousands of other films might have been made to try to convey what others went through in their passage from Sudan to the United States. However, these two men provide a vivid sense of the range of reactions to devastation and dislocation. Peter seems resourceful—and self-centered—enough to succeed in America, but Santino, still shaped by a communal culture, seems to have succumbed to depression.

Absent entirely from the documentary are the lost girls of Sudan, lost more thoroughly and irrevocably than their male siblings. We can only imagine the horrific fates that befell young women off-camera—rape, sexual bondage, murder. Mylan and Shenk conclude by noting that there are currently 15 million refugees in the world. Few of them ever show up on camera. Though the United States took in 70,000 refugees in 2001, including 4,000 lost boys of Sudan, few Americans, currently fixated on Iraq, pay much attention to the largest country on the African continent, Sudan. But the crisis in east Africa grows ever more severe. During the lost boys’ stay in America, violence by the Janjawid Arab militias in Darfur has displaced an additional one million black Sudanese. This hardly seems an auspicious time for Peter and Santino to return to their native land. The longer they tarry in the United States the easier it becomes for them to forget their Dinka culture. Suspended between two worlds, they seem less and less likely to return to Africa. During one scene in the film, Santino attends a celebration in Houston of Sudan Liberation Day. That day now seems more remote than ever.

A contributing writer to The Texas Observer, Steven G. Kellman teaches comparative literature at the University of Texas at San Antonio.