More Power, Less Grace

Surely loyal supporters of The Texas Observer will get at least a little pissed off when they learn President John Kennedy—who already had a veritable revolving harem—was such a greedy sex maniac that he stole the girlfriend of one of this publication’s most famous editors, Bill Brammer.

Only a few months after Kennedy’s inauguration, Hugh Sidey was working late in Time magazine’s Washington bureau when he was interrupted by Brammer’s lovelorn complaint. Little Billy said he had just learned the young woman he was dating, Diana de Vegh, was also having an affair with the President. He told Sidey that he had asked her why she did it. “Nothing will come of it,” she is said to have replied, “but he has a hold on me.” What kind of hold? “Power,” she answered.

So there you have it: Power—the second half of this fluffy book’s title. And Kennedy seems to have used it much more often to get women into bed than to fix national and international problems.

But Brammer never lost his sense of humor. Several months later he wrote a friend in Texas:

Jack Kennedy is down in his back, and this has apparently limited his roundering, for he does not often call to bug his teenage mistress to whom I am secretly engaged. Very late on a recent evening a voice that was unmistakably our Leader’s reached me on the phone, inquiring of ‘Diaawhnah.’ (I started to say she’d gone to ‘Cuber’ for a week and a hawrf.) I informed him that she was in the bawrth, tidying herself, and he rang off rather abruptly.

Obviously, Brammer was a much better novelist than reporter because Kennedy’s being “down in his back” didn’t even slow his roundering. The index shows that Sally Bedell Smith, our author, devotes all or portions of 154 pages to writing about Kennedy’s “affairs.”

Kennedy’s back was indeed a bummer—once he had to have a cherry-picker lift him into Air Force One—but that didn’t stop his roundering, no sirree, because he had the able assistance of Max Jacobson, better known as “Dr. Feelgood” to his rich and famous clients who floated through life on his injections.

Before his debate with Richard Nixon and to prepare for his State of the Union speeches and before dealing with leaders in Europe—aside from the dozens of times he just needed a shot to steady himself around the White House—Kennedy called on “Dr. Feelgood” to use the needle. On one occasion, taxpayers footed the bill to fly “Dr. Feelgood” and his wife to Europe—the only ones on the Air France plane.

When brother Bobby suggested that he lay off the drugs, the President replied, “I don’t care if it’s horse piss. It works.”

In Kennedy’s 14 years in the House and Senate, he had shown no leadership or imagination. He won election to the presidency in 1960 by the smallest margin in 100 years, and he surely would have lost the election if voters had known of his serious physical defects—some of which caused such pain they must have clouded his reasoning. Kennedy successfully covered up the fact that since 1947 he had had Addison’s disease, which can be fatal. By the time he was 40, he had been given the Catholic last rites four times.

Lyndon Johnson would certainly have known of Kennedy’s serious illness. (After all, LBJ was a bosom buddy of J. Edgar Hoover, who knew everything.) Did it influence his acceptance of the dreary and often insulting job of being Kennedy’s vice president? Sally Bedell Smith says LBJ told Clare Boothe Luce, “I looked it up. One out of every four presidents has died in office. I’m a gamblin’ man, darlin’, and this is the only chance I got.”

Top journalists helped Kennedy cover up his physical defects, his womanizing, and his bungling of foreign policies. Indeed, there were more press whores around Kennedy than there were mistresses. Arthur Krock of The New York Times helped Kennedy write Profiles In Courage and then, says Smith, he “log rolled” the Pulitzer committee into giving Kennedy its prize. Famous columnists such as Joseph Kraft and Walter Lippmann constantly sucked up to Kennedy.

And when Kennedy appointed brother Robert to be attorney general—”a brazen act of nepotism,” Smith accurately calls it—the press scarcely muttered. And in the Senate, another house of ill repute, only one member cast a vote against Robert’s confirmation.

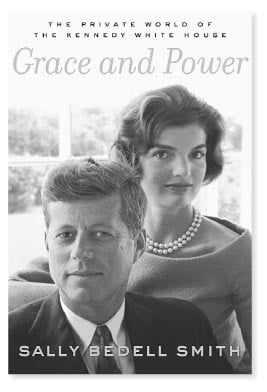

In Grace and Power, “grace” is represented by social occasions of various degrees of foppish and often drunken excess; “power” is represented by an appallingly stupid political atmosphere.

The most pressing domestic problem facing the Kennedy administration was the civil rights war in the South. But in the first 300 pages of this book, there are only three short entries to cover his indifference to it. Page 176: “Black voters had contributed significantly to Kennedy’s victory, but he had no appetite for taking a stand in Congress for desegregation against the dominant southerners of his party.” Page 203: When Freedom Riders were attacked by Alabama rednecks, Kennedy asked Harris Wofford, his civil rights adviser, “Can’t you get your goddamned friends off those buses? Stop them!” Page 296: “In Washington the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation was being celebrated in front of the Lincoln Memorial.” Kennedy didn’t attend the ceremony and that “was consistent with his hands-off approach to civil rights.”

The dirtiest trade-off in the book went like this: FBI director J. Edgar Hoover wanted to bug and wire-tap Martin Luther King, Jr.’s hotel rooms to catch the conversation and sound of bedsprings when King entertained his women. But Attorney General Robert Kennedy refused to authorize electronic snooping. Then the Senate geared up to investigate a whorehouse operating on Capitol Hill. An East German woman suspected of being a spy worked there. She was also one of the President’s girlfriends and had visited the White House several times. Brother Bobby knew J. Edgar Hoover knew this and would be subpoenaed to testify at the Senate investigation. For Hoover’s silence, Bobby gave him permission to eavesdrop on King.

In foreign affairs, Kennedy was a cocky nincompoop. Shortly after taking office, he did away with regular sessions of the National Security Council and disbanded the NSC’s staff support group—”a move that eliminated a rich source of analysis from agencies and departments.”

He was so smart, he didn’t need their advice. The original plan for the Bay of Pigs invasion was for it to begin in the port of Trinidad, adjacent to mountains which would give a haven for escape if necessary. “But Kennedy wanted a quieter scheme, so the planners shifted to the more remote Bay of Pigs, which as it turned out, was totally hemmed in by impassable swamps.”

Throughout the planning, says Ted Sorensen (one of the few level heads in the White House), Kennedy “was indecisive and vacillating.” And when the plan was literally falling apart but the situation could be saved because the invasion had not yet taken place, Secretary of State Dean Rusk urged Kennedy to cancel it. Instead, we learn, our great president paid no attention and “tried to distract himself by whacking golf balls” with buddies at two country clubs.

Power having failed again, we quickly return to Grace. Two days after the Bay of Pigs disaster:

Jack and Jackie hosted a gala reception for members of Congress. Wearing a Cassini-designed sheath of pink-and-white straw lace, a feather-shaped diamond clip in her hair, and an impish look, Jackie whirled around the dance floor with Lyndon Johnson.

You learn too much about Jackie’s clothing from Ms. Smith and not enough about LBJ’s dancing. But there is one other dance we are told about, and for me it is the high point of the book:

The black-tie candlelit dinner dance for eighty… offered perhaps too much fun… Oleg Cassini introduced the twist, which originated at New York’s Peppermint Lounge [and] was considered improperly suggestive… The champagne flowed until 4 a.m., and many partygoers got hopelessly drunk.

Among the most hopeless was Texas’ own Lyndon, who was dancing with one of Kennedy’s prize girlfriends, and suddenly Lyndon collapsed. Just slid to the floor. Splat! Out cold. Unfortunately, he was still holding onto Kennedy’s girlfriend, who was trapped on the floor under him. It took several partygoers to hoist the vice president off of her.

The book includes a sufficient sprinkling of such bawdy occasions, many proudly admitted mistresses on and off the public payroll, boring displays of wealth, betrayals of friends (such as Adlai Stevenson), incompetent executive planning, and toadying by staff satellites (such as Arthur Schlesinger, who considered Kennedy “nearly infallible”) that you will know you have been given an authentic look inside the Kennedy White House.

Frequent Observer contributor Robert Sherrill divides his time between Florida and Texas.