Capitol Offense

Who You Gonna Call?

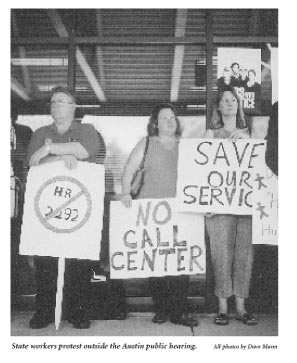

April 30th was billed as the day that thousands of state health and human services workers would have a chance to speak out against a state proposal to abolish their jobs. The state is planning to shutter more than 200 local social services offices and lay off thousands of enrollment workers in favor of three privately run call centers. Poor Texans will presumably enroll in government assistance programs much like they would buy an encyclopedia set off late-night television. This is one of the most controversial portions of the unprecedented overhaul of the Texas welfare system that passed last year. In the next five months, state officials will finish scrunching 12 health and human service departments into four heavily privatized mega-agencies. The reorganization is the handiwork of right-wing state lawmakers and their handpicked administrators who seem determined to morph the state’s safety net into a money-saving pseudo-corporation. It’s as if Texas has handed over its government healthcare system to Wal-Mart.

State enrollment workers were afforded at least one chance to be heard. Administrators scheduled 10 simultaneous public hearings around the state on April 30 to glean input from state workers. Hundreds of workers took the afternoon off work to attend. In reality, however, they didn’t get much of a say. Many key decisions had been made weeks before. In closed-door meetings, state administrators had fashioned the call-center plan with private contractors from some of the very companies that potentially could benefit from the new system they’re helping to design.

Since October of last year, a group of 24 state health officials and private contractors has gathered almost every week for meetings at the Austin headquarters of the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC). The group’s mission: to recast the way poor and vulnerable Texans enroll in programs such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, food stamps, and welfare cash assistance.

Currently, latching on to the government rolls requires a visit to one of about 380 Department of Human Services offices, where a state worker determines whether you’re eligible for government assistance and then helps you enroll. By most accounts, the system, while far from perfect, functions serviceably. During the 2003 legislative session, however, state lawmakers decided that system had to go. They passed a sprawling healthcare consolidation bill (House Bill 2292) that cut numerous services and privatized several others to fit a vision of limited government [see “Legislative Malpractice,” June 20, 2003].

In the name of greater efficiency, the legislation ordered state officials to examine scrapping the current eligibility and enrollment system in favor of three or four privately run call centers. No state in the country has ever employed call centers to such an extent or completely privatized such a core government function. It’s a massive undertaking, in both size and importance. About four million Texans rely on some form of social services at a cost of nearly $22 billion a year in state and federal funds.

State health commissioners have handed this responsibility primarily to the 24 healthcare and technology experts who comprise what’s known within the HHSC as the integrated eligibility study team. “These folks have really done the front-line work on this project,” HHSC spokesperson Stephanie Goodman said of the team. “They played a very integral role in developing this [integrated call center] proposal.”

In addition to state administrators, however, the group includes at least seven contractors from private companies, including Cisco Systems and two telecommunications firms, according to internal HHSC documents and meeting agendas obtained by the Observer through the Texas Public Information Act.

In early March, the HHSC released a proposal that filled in many of the previously missing details of the call-center plan. The agency termed it a “call-center business case.” The report proposed closing more than 200 of the 380 local offices around the state and firing 4,500 state eligibility workers (a 57 percent reduction). The plan would represent a huge shift toward a leaner, privately run gatekeeper to state social services. The business case estimated that this model would save $389 million during the next four years. The 24-member integrated eligibility study team, according to several sources, wrote the call-center business case almost entirely. That may have led to conflicts of interest.

One of the report’s revelations was the HHSC’s plan to use the 2-1-1 telephone system as the access number for the call centers. Much like 9-1-1 and 4-1-1, the federal government has designated 2-1-1 as a healthcare information hotline. In 2001, the state contracted with the Chicago-based telecommunications company eLoyalty to set up Texas’ version of 2-1-1. The system was launched last summer amid a flurry of press releases. Under the call-center plan, 2-1-1 would be expanded from a simple info hotline to the main number that needy Texans would call to tap into all state social services. This almost certainly will provide eLoyalty with more business from the state. In fact, three eLoyalty workers serve on the integrated eligibility study team that helped write the very proposals that would bring in new business for their firm.

Goodman, the HHSC’s spokesperson, said that the state has long planned to use 2-1-1 as the access number for call centers and wanted eLoyalty’s expertise on the study team. HHSC denies there is any conflict of interest because eLoyalty already contracts with the state. Goodman said the agency’s policy is that no company that doesn’t already work with the state can serve on the study team and bid on future contracts. In eLoyalty’s case, the firm wouldn’t bid on a new contract but would simply expand its current deal.

Nevertheless, the case of eLoyalty shows the influence private contractors may be exerting over the HHSC overhaul. It has become routine for governments to outsource such mundane necessities as garbage collection and paperwork filing. But it’s unusual for private companies to actually formulate essential government policy.

The state eligibility workers, meanwhile, don’t have such access. Neither HHSC chief Albert Hawkins nor any of the agency’s associate or assistant directors attended any of the 10 public hearings on April 30th. The man hired to oversee the HHSC revamp, Gregg Phillips—a former Republican campaign operative and architect of Mississippi’s failed stab at privatizing welfare—lingered at HHSC headquarters to “monitor” the hearings, Goodman said. He didn’t, however, hear any of the testimony.

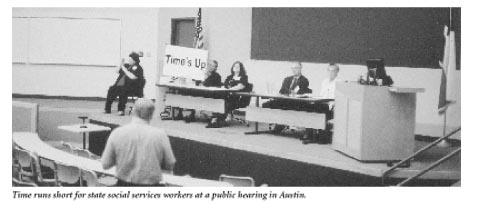

HHSC officials had foisted the job of actually overseeing the public hearings on regional administrators—mid-level bureaucrats who have little say over the call-center plan. Regional directors Kathy Cox and Robert Arbuckle had this thankless job at the Austin hearing. For five hours, they sat on stage in a sterile-looking classroom at a far-flung University of Texas research campus. Hands folded in laps, they listened to their staff complain about a plan that none of them had designed.

Many speakers hit on the same points. Standing at a microphone directly in front of the stage, they argued that the call-center plan has been rushed. They said that trying to install call centers by October borders on reckless. Others noted that the new computer mainframe on which the entire call-center system will run is still riddled with glitches and has yet to emerge from the trial phase. A few workers pointed out that the current system is holding up pretty well given that the Legislature had cut their funding by 44 percent since 1997. Employees’ workloads have since doubled. Workers from small towns said that closing so many state offices and terminating so many employees could devastate rural communities. And numerous speakers broke down when talking about how much they loved their jobs and the people they helped. Cox and Arbuckle sat expressionless, no matter what was said. (This lead one observer to remark, “You’d think they had been told that if they smiled, they’d be fired.” That might not be an exaggeration, given the almost military-like leadership exhibited at the HHSC lately.)

Celia Hagert, a policy analyst at the progressive think tank, the Center for Public Policy Priorities (CPPP), testified that the call-center proposal contained some good ideas. But, she said, the HHSC had failed even to study whether staffing levels in the current system are adequate. In fact, she said, the agency had seemingly done no analysis of how many workers, public or private, it would need to enroll millions of Texans in social service programs. As a result, much of the HHSC’s business case, Hagert said, consists of arbitrary assumptions. If the call-center plan goes awry, the state stands to actually lose money because thousands of Texans might be refused benefits to which they’re legally entitled. The resulting loss of federal matching funds would easily erase the estimated savings from utilizing call centers in the first place.

But even when speakers were making damning points such as these, it seemed unlikely that the comments would have any impact or that the absent power brokers from HHSC would even hear them. No matter what was said, when each speaker’s allotted five minutes of testimony expired, an assistant simply held up a large white sign that read, “time’s up.” Cox then called the next name. It was as if people were testifying in front of their bathroom mirror. And the hearing soon took on the feel of a meaningless exercise: public input as window dressing.

As the hearing stretched into its third hour, Reuben Leslie became irate. When his turn to testify came, Leslie, a tall Department of Human Services administrator sporting a gray suit, approached the microphone and asked incredulously, “Will these comments be posted on the [HHSC] Web site?” Cox and Arbuckle just stared back at him. “I’ll take an answer now if you have one,” Leslie said. Cox and Arbuckle looked at their feet. Realizing no response would be forthcoming, Leslie continued. “Where are the commissioners?” he demanded. “Is there anyone here who works for HHSC?” He turned from the front microphone and scanned the room. “Raise your hands.” One hand went up. “We’re moving toward a cabinet-style government here in Texas,” Leslie continued. “Holding public hearings at 3 p.m. on a Friday on the last day of the month at 10 hard-to-reach sites around the state is not engaging your stakeholders.” At this point, the “time’s up” sign was flashed at Leslie. But he was on a roll and ignored it. “Hopefully, Texans can wake up before election day and turn out everyone who voted for House Bill 2292 and replace them with people who care about Texans.”

HHSC’s Goodman later said that the agency will post summaries of the public hearings on its Web site. Meanwhile, the agency expects to request private bids to run the call centers in June. Given the project’s many hiccups, however, and what critics label as HHSC’s bungled planning process, meeting the October deadline may be impossible. “The [call center] model, if it were adequately staffed, would probably work, if the technology works, and that’s a big if,” said CPPP’s Hagert. But, she added, the HHSC’s implementation of the system has skipped so many key steps that “we suggest that they start over.”