Las Americas

The Politics of Death

The death penalty always seems to provide fodder for the myths of the living. One of the more widely circulated myths is that Mexico is de jure abolitionist—that capital punishment does not exist.

After all, President Vicente Fox has made much of his general opposition to death sentences, especially those handed down to Mexican nationals in the United States. The Mexican government provides impressive legal assistance to more than 50 of its nationals on U.S. death rows (see “la Abogada de Mexico,” October 25, 2002). Late last month, the World Court in the Hague found that the United States violated the rights of these nationals and ordered American authorities to provide meaningful review of their sentences.

But Mexico’s own Constitution permits the application of the death penalty in cetain circumstances—for homicide, arson, kidnapping, as well as for treason and grave military crimes.

Last November a military court imposed death sentences upon two soldiers convicted of killing superior officers; Fox commuted the sentences to life in prison. He has intermittently stated his intention to take capital punishment off the books once and for all, but so far little legislative progress has been made.

To understand how the death penalty affects Mexico’s domestic and foreign policies, the Mexican Center of the University of Texas has organized a one-day, public symposium with scholars, lawyers, and public officials on April 14. The symposium coincides with an exhibition of rare materials held by UT’s Benson Latin American Collection documenting the history of capital punishment in Mexico. The exhibition reveals how Mexico has experimented with retaining and abolishing the death penalty, often to reinforce the legitimacy of a particular government.

Among the images is that of a 1780 execution that depicts a garroting in Mexico City’s central plaza. The garroting took place outside the royal palace; afterward authorities hoisted the bodies on a scaffold to show the crowd.

Were such executions common? According to historians of colonial Mexico, the Spanish used the death penalty infrequently and only for the most heinous of crimes. With Independence in 1821 the number of executions soared as a weak Mexican state sought to consolidate itself through repression. Antonio López de Santa Anna (better known to Texans as the victor of the battle of the Alamo) was referred to as the “Harlequin Hangman,” because of frequent political executions.

In 1857 the Liberals (Mexico’s heirs to the “Enlightenment”) proclaimed a new Constitution with enhanced guarantees for individual rights. It provided for the abolition of the death penalty for political crimes, and made complete abolition for ordinary crimes contingent upon the construction of a penitentiary system. (The Liberals considered themselves agents of progress and believed the penitentiary could rehabilitate all criminals, thereby making the death penalty unnecessary.)

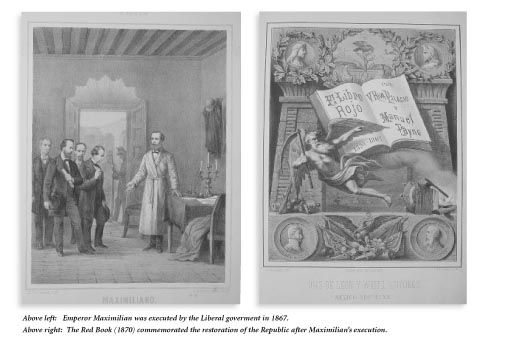

Reform would have to wait, however. It would be another 10 years before the Liberal Party had control of the country, after Benito Juárez and the Mexican Army defeated Maximilian, the puppet Emperor whom Napoleon III had installed. On June 19, 1867, the Liberal government executed Maximilian.

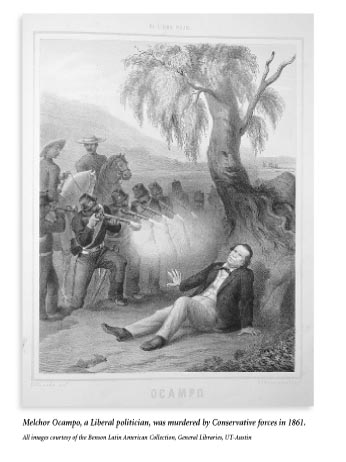

In response to criticism from Europe and the United States, two leading writers and politicians, Vicente Riva Palacio and Manuel Payno, constructed a romantic myth of their party’s commitment to fair play in El Libro Rojo (1870). The Red Book, which is currently on display in the Benson, detailed numerous executions from 1520 to 1867. A remarkable resource, it can be read as an excercise in 19th-century political spin. Images of the colonial and early national periods portrayed death as a violent presence. But when they depicted executions for which the Liberals were responsible, the book’s lithographers took another approach. An image referring to Maximilian’s execution, for example, portrays the Emperor in discussion with his legal team. The Liberals’ romanticizing of their commitment to the law meant that executions would continue throughout the 19th century.

Of course the politicization of the death penalty is not limited to one side of the border. The exhibit and symposium seek to explain the trajectory of the death penalty in Mexico, its effect on international relations, and the possibilities for full abolition emerging from the Mexican government’s protest of executions of its nationals in Texas and throughout the United States. Mexico’s experience with and history of capital punishment should cause those of us living north of the border to re-examine the value of the death penalty in the modern world.

Patrick Timmons, a doctoral candidate in the History Department at the Univeristy of Texas at Austin, is organizing the symposium, “The Death Penalty and Mexico-U.S. Relations,” at the Mexican Center of the University of Texas. For more information, see the Center’s website at www.utexas.edu/cola/llilas/centers/mexican. For information about the Benson Latin American Collection, see www.lib.utexas.edu/benson.