Police Pre-Emption

Police documents reveal a campaign to infiltrate Austin anti-war demos

A year ago, as the Bush Administration prepared to launch a pre-emptive war on Iraq, activists all over the nation mobilized in protest. In Texas, Austin was a focal point for demonstrations and civil disobedience. Now, official documents obtained by the Texas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union reveal that the Austin Police Department launched its own pre-emptive action against peaceful protesters: infiltrating local anti-war groups and allegedly using the information to target suspected leaders for arrest for minor infractions.

On March 15, 2003, at a rally at the Texas Capitol, American Friends Service Committee organizer Missy Bolbecker announced a week of nonviolent direct actions to start March 17. The anti-war activities would culminate in mass civil disobedience on March 24. Her call echoed a national appeal issued by a newly formed anti-war coalition; and Bolbecker herself served as Austin’s designated coordinator for Iraq Pledge of Resistance, one of the participating groups. She also helped to organize direct action trainings and meetings with local activists to plan actions in response to the national call. (In the interest of disclosure, I was outraged by the war and participated in the civil disobedience as well.)

The “Unholy Trinity Tour” emerged from these meetings. The tour consisted of a march around Austin on March 24, targeting the Federal Building and two businesses accused by protesters of facilitating the United States’ assault on Iraq. The businesses were Fox 7 News, selected for biased pro-war reporting, and Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC), picked for its recent merger with military contractor DynCorp. During the tour, seven demonstrators were arrested in front of Fox affiliate KTBC-TV, some for chaining themselves to street signs and effectively blocking the exit to the building’s parking garage. Another 33 people were later arrested for impeding traffic in front of CSC. Earlier in the week, police equipped in riot gear arrested 50 people on the Congress Avenue bridge. One officer employed pepper spray to forcibly disband the crowd.

Many protesters suspected at the time that they were the focus of an intense surveillance campaign by the Austin police. The extent of that campaign is detailed in two memos written by police officials in the Organized Crime Division of the APD. According to a memo from Sgt. Troy Long to APD Chief Stanley Knee, four detectives were “requested to participate in training sessions and actual protests in an undercover capacity.” In the memo, dated June 3, 2003, Sgt. Long trumpeted their successes, declaring, “Detectives were able to befriend the organizers and leaders of the anti-war protests. The Detectives became privy to information regarding future protests and planned mass civil disobedience.”

The memo seems to contradict an Austin City Council resolution passed three months later on September 25, 2003. The resolution pertained to police infiltration and the USA PATRIOT Act, and stated:BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the Austin Police Department shall continue their policy of not conducting surveillance of individuals or groups of individuals based on their participation in activities protected by the First Amendment… without reasonable and particularized suspicion of criminal conduct unrelated to activity protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.As allegations of police surveillance escalated after the resolution’s passage, City Council Member Daryl Slusher met to discuss the issue with APD Assistant Chief Rick Coy on January 26, 2004. Coy wrote Slusher a memo two weeks after their meeting to explain why the chief may have mistakenly given the council a misleading sense of the scope of police surveillance of activist groups. “He [Knee] feels badly that his communication was not clear enough to explain all of our undercover activities, leaving you with the impression that no officers had been involved in other areas away from the actual protest site.”

The memo also maintained that while “undercover officers do, in fact, mix with protesters in the public domain,” APD does not keep files on protesters. It additionally mentioned that a city attorney was consulted prior to the officers’ infiltration.

However, the memo from Coy (Knee’s chief of staff) and the memo from Sgt. Long (addressed to Knee) seem to contradict each other regarding the number of times undercover officers attended activist training sessions. Coy implies that APD only infiltrated a single “protestor training meeting” in his memo. But Long reported to the chief, “Detectives attended protest training sessions, planning sessions and protests.”

Police activity was not limited to just infiltration and intelligence gathering. Long also wrote, “Detectives further assisted in the assignment and deployment of Crowd Management Team (CMT) personnel by providing video footage of the organizers/leaders of the protests.” The Observer contacted CMT Commander Robert Dahlstrom for comment. Dahlstrom admitted that police frequently film protests. “We always do that, it’s not a secret,” he said.

The second memo acquired by the ACLU was dated March 25, 2003, and entitled “War Protest Intelligence.” In it Detective Derry Minor detailed four pages worth of intelligence gathered while undercover at a direct action training session at the downtown Austin AFL-CIO building two days earlier. In the memo, Minor wrote he “positively identified two local leaders/organizers from Austin,” and one of them was “Melissa” Bolbecker.

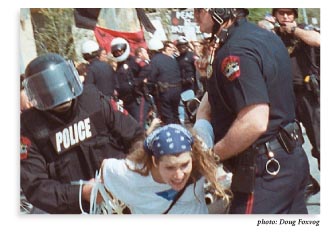

On March 24, 2003 (the day after Minor’s infiltration), at the Unholy Trinity Tour’s stop in front of CSC, activists claim that Bolbecker was targeted from a crowd of hundreds and arrested. Police had ordered protesters off the street in front of CSC’s offices and onto a sidewalk on either side of the street. Most protesters complied, Bolbecker included, several witnesses say.

The sidewalk across the street from CSC’s offices backs onto a slope, which drops off sharply to the hike-and-bike trail beside Town Lake. In order to traverse the congested sidewalk, some people briefly stepped off the curb to pass others, said Doug Foxvog, a member of the activist group Austin Against War. “Missy stepped off the curb to do this very thing and was grabbed. It was definitely a case of selective arrest,” he said.

According to Bolbecker, who reports that only the police call her Melissa, “I’m not even sure both feet were on the ground before I was snatched by a riot cop, who twisted my arm behind my back and began forcing me toward the paddy wagon.”

Bolbecker initially received the same charge as other activists—”Obstruction of a Highway Passageway” (a Class B misdemeanor)—who had engaged in civil disobedience in the center of Cesar Chavez Street, some by staging a symbolic die-in while others sat with interlocked arms, refusing to move. (In the end, Bolbecker was charged with failure to obey a lawful order.)

Joshua Elliott, a recent University of Texas physics graduate, was arrested later that day, ironically, on a march to APD’s central booking station. In a sworn affidavit taken by defense counsel for one of the criminal cases against the activists, Elliott testified that while being transported to booking he asked an officer with whom he had a friendly relationship from previous encounters why Bolbecker had been arrested. “He had not been involved in her arrest but immediately knew who I was talking about and he then told me that she had been labeled a facilitator of the event and he told me that you don’t want to be labeled as a facilitator because that will get you arrested,” Elliott testified.

Eric Laulus, who attended the protests that day, reported seeing a man wearing a suit jacket carrying a clipboard containing sheets with photos of individuals. “I saw them because the wind picked up and a few fell to the ground,” Laulus said. “I saw pictures of people with text to the right of the pictures. A few minutes later, I saw the man speaking with police officers, pointing at his clipboard.”

Dahlstrom declined to comment directly when asked whether Missy Bolbecker was selectively arrested by CMT, but did recall that one individual was arrested after being warned multiple times to stop stepping off of the sidewalk. He could not remember if that person was Bolbecker. “I wouldn’t even know who she was had I not seen her picture in the paper,” Dahlstrom said.

Four days before the Unholy Trinity Tour, on March 20, 2003, anti-war protesters Brandon Darby and Ron Deutsch attended an impromptu rally on Guadalupe and 24th Streets. There, 15 activists (including this author), had secured their arms together in giant “lock boxes” in order to occupy the intersection in protest. Darby says he entered Einstein Bros. Bagels to buy coffee for the locked-down protesters when he noticed an awkward looking group of men. “They were all reading the front page of different newspapers, not talking to each other, some with ear pieces,” recounted Darby.

In an attempt to confirm his suspicions that they were undercover police, Darby said he talked with them briefly and then jogged down the street to catch up with the protesters, who were then marching toward Congress Avenue. Darby said that after noticing that the men from the bagel shop were following him he ran inside a gas station to purchase a disposable camera for evidence in the complaint he planned to file with APD.

Deutsch, a journalist who has written for the Austin Chronicle and Austin American-Statesman, told the Chronicle that he was tackled and arrested upon trying to photograph the suspected undercover officers. After pleading for the men to show their badges, Darby said he, Deutsch, and another man were thrown into the back of an unmarked van where one of the suspected undercover officers yelled at them, “You want to see my badge? Austin po-po, motherfucker!”

At central booking, Darby said he was accused of being under the influence of cocaine because his heart rate was measured at 122 beats per minute. Darby, an asthmatic, said he tried to explain to them that he was only scared. Later, Darby was asked by a police officer whether he was “part of a national underground organization of people that take photographs of undercover police so that people can assassinate them,” he said. Darby was given a citation for “pedestrian in a roadway” while Deutsch was charged with jaywalking.

In the second memo, Minor—who, according to a Google search, served as Dripping Springs’ Pinto League Baseball Commissioner for the 2002-2003 season—expressed concern over activists acquiring and publishing the names and pictures of undercover police officers. He wrote: “Websites were mentioned for antiwar protesters. I have looked at these websites and observed that they are posting pictures of the officers at the protests on these websites. The tactics of antiwar protesters obtaining photographs and names of officers making arrests and posting them on the internet jeopardizes the safety and integrity of the organized crime detectives who work in undercover capacities on a daily basis.”

The Austin Independent Media Center (www.austin.indymedia.org), was one of the few, if not only, websites that contained photos of undercover APD officers. According to Tanya Ladha, a member of Austin Indy Media, the online database of undercover police was recently hacked into and erased. It was replaced by the message “Try, try again.” She says that the password necessary to hack into the site was only revealed once in an e-mail between two of the group’s members.

In Sgt. Long’s memo, he wrote of how difficult it was to “infiltrate a culture of society that is highly suspicious of new members.” Minor reported that “leaders closely scrutinized [his] presence.” Dahlstrom admitted that some officers blended in better than others. “One got along with everybody real well and another one had people yelling, ‘Cop! Cop!'” he said. Minor wrote in his memo, “I was questioned about my name and why I was there. After passing this test, I was allowed to stay for the training.”

But according to Scottie Buehler, a UT student and the other “leader/organizer” identified by name in Minor’s memo, the “test” Minor was forced to undergo may have been nothing more than the standard icebreaker for many local activist groups. At the beginning of the training session, all attendees were asked to state their name and whether they had an arrest record. Buehler acknowledges that it is possible that someone else grilled the detective privately but said she is unaware of that happening.

Although open record requests have already revealed APD’s assignment of at least four detectives for infiltration purposes—Derry Minor #2010, James Green #2361, Robbie Volk #3278, and Tamara Joseph #2268—more information on the police’s clandestine activities may be on the way. The Austin People’s Law Collective, an activist group specializing in legal defense and education, claims that despite APD having more intelligence on Austin protesters and organizers, they refuse to release the information.

According to a public statement by APLC, the collective’s objective is to help “people understand that their rights are being violated and that they have a medium for finding out what the state is up to (via open records requests) and holding them accountable for their actions.”

In December of 2003, APLC filed open records requests asking for any memos, correspondence, databases, videos, photographs, informant reports, or files related to APD’s documentation of Austin activists and activist groups. APD refused to fully comply. Consequently, APLC is currently awaiting judgment from Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott as to whether APD is legally compelled to release the requested information. (The Department of Public Safety was more responsive to APLC’s open record requests; DPS turned over a CD containing candid photographs of individual protesters at demonstrations and the times and locations of local protests.)

For the ACLU, the actions of the Austin police are another indication of how a post 9-11 backlash has imperiled the First Amendment. “The police secretly infiltrating meetings chill the First Amendment rights of protesters to freely associate,” believes Will Harrell, executive director of the Texas ACLU. “But when they use those meetings to identify leaders and actually target them, it becomes a McCarthyite nightmare. This is a textbook example of why the framers of our constitution provided for the freedom of association in a free society.”

Jordan Buckley is an Austin activist and honors student at the University of Texas. He is currently studying sociology at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina.