Fund and Games

Will the lege cheat on school finance?

Texas children went back to school this fall in districts strained almost to the breaking point. School boards scrambled all summer to balance district finances, laying off teachers, aides, and office workers, jettisoning enriched curriculum, and delaying the purchase of vital supplies. The Austin Independent School District cut about 650 positions, slashing nearly one third of its elementary art, music, and PE teachers. The district’s average pay raise of 1.2 percent left most teachers making less than they did last year, once you factor in state cuts to teacher health insurance premiums. Despite the district’s financial woes, the state also hit up AISD—a so-called property-wealthy district—for $158 million in recapture payments under the 1991 wealth equalization system known as “Robin Hood.†San Antonio’s Northside Independent School District, a property-poor district that received almost $19 million in Robin Hood money in 2003, also had a bad budgeting year. The district carved $22.7 million from this year’s budget by raising student-teacher ratios, freezing salaries, and cutting almost 200 positions, including teachers and counselors. Budget cuts this deep, and deeper, were the norm this fall. In a state that will likely add at least 90,000 new students in the next few years, where educators are expected to boost TAKS scores ever higher, the schools are simply running out of money.

Between 700 and 800 districts are at or near the state-imposed $1.50 property tax cap. Districts with low property wealth, like San Antonio’s Northside, must tax at the cap just to keep their schools afloat. Property-wealthy districts tax at the cap to compensate for their staggering recapture payments. Urban districts raise taxes to pay the high costs of their bilingual and economically disadvantaged students; rural districts, to offset losses in state funding that accompany their declining enrollments. With no way to raise additional revenue, they are all forced to cut costs.

“Whether you’re wealthy or poor, everybody is experiencing a great deal of strain,†says Karen Soehnge, director of governmental relations for the Texas Association of School Administrators. Despite urging from legislators to trim the fat, most districts can’t cut much closer to the bone.

“Reducing supplies doesn’t make a lot of difference,†Soehnge says. “The only way you can take the strain off the budget is in personnel—office staff, administrators, eventually teachers.â€

The problem, say school finance experts—at least, those outside the statehouse—is simple. There is just not enough money in the system. The state currently pays for about 38 percent of the cost of educating its children, with the rest coming from local property taxes and a negligible contribution from the federal government. The Robin Hood system, which collects “excess†money from rich districts and redistributes it to poorer ones—works only if there is excess money. In tight times, the system pits districts against each other in a fight over scarce resources. Most experts agree the Texas system is reasonably equitable—property-poor districts don’t end up with too much less than property-rich districts. But equity doesn’t mean much if everyone is doing equally badly.

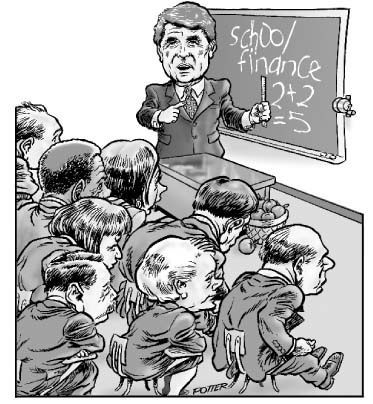

When it comes to school finance, the Lege seems to be having trouble doing the math. All legislators will tell you they want Texas schools to be the best in the country. Most say they want to slash the property taxes that are the chief source of school financing. Many think they can do both without raising new taxes. To make these figures add up somehow is presumably the job of the Select Joint Committee on Public School Finance, appointed by Governor Rick Perry last spring to ready fellow legislators for a school finance special session. But the prospects for a special session are getting dimmer, as the Joint Committee discovers what any good math teacher could have told them all along:You don’t get more money by taking money away.

Last spring the governor led the public to believe that a special session to resolve school finance was a foregone conclusion. In recent months, however, his enthusiasm has waned, and it’s easy to guess why. Though unlikely to spur another walkout, school finance reform could be every bit as ugly as redistricting, and this time divisions won’t fall predictably along party lines. The majority of legislators, including most Republicans, represent the nearly 90 percent of school districts that benefit from Robin Hood.

“The governor fully expects to call a special session in April,†says Kathy Walt, Perry’s press secretary. But first he wants to be sure members in the House and Senate “agree on the general approach†to reforming school finance. That agreement could be a long way away. (Perry may also be hoping to keep an ugly and potentially embarrassing special session out of public view until after the March primaries. Thanks to legislative redistricting, in many districts primary elections are the only ones that matter. And if the Lege can wrap school finance up, however clumsily, before summer, voters may not remember it by the time they reach the polls in November.)

The school funding system’s heavy reliance on local property taxes means there will always be a money gap between rich and poor districts. With its higher property values, Plano ISD can always raise more, and at a lower tax rate, than El Paso. Before the state started equalizing funding more than a decade ago, the richest districts raised and spent up to 700 times what the poorest could muster. So call it Robin Hood or call it what you like, as long as property taxes fund the schools, the state will have to make up the difference between rich and poor.

At the same time, there’s every incentive for legislators to end Robin Hood. Many—especially the new wave of suburban Republican freshmen—campaigned on a promise to do just that. The system has always been unpopular with rich districts, and a lawsuit against the state, started by wealthy districts, claims the system takes away local discretion to raise and spend taxes as they see fit. Meanwhile, the property taxpayers who fund the system are sick of rate increases. And while property tax relief has largely been cast as a Joe-Taxpayer issue, it also represents a huge tax cut for businesses; about 60 percent of local property taxes are levied from commercial rather than residential property. If legislators are serious about eliminating Robin Hood, they’ll have to replace local property taxes with some state money. That means those dreaded two words, “new taxesâ€â€”an option so many loudly rejected on the campaign trail in 2001. In the three-way tug-of-war between schools, taxpayers, and business, every legislator will have to hammer out his or her own devil’s bargain. So legislators “hope for†a session. They “expect,†“understand,†and “trust†that their governor will call one. But perhaps privately many have their fingers crossed, hoping it’ll all just sort of blow over.

The vision of Rep. Kent Grusendorf (R-Arlington) may be the best example of the sort of pipe-dreaming going on at the Lege these days. Grusendorf, who co-chairs the House side of the Joint Committee, proposes an expanded system of standardized testing, to be carried out online. While costs for such a program are likely to be high, Grusendorf also supports cutting property taxes up to 80 percent—leaving the state with almost $13 billion to make up from somewhere. Grusendorf doesn’t envision generating this money by new taxes, suggesting the state can instead scrounge the money up through some simple “tax restructuring.â€

This sort of wishful thinking isn’t uncommon around the Capitol at the moment. But most aren’t too precise about what sort of restructuring they have in mind. Some hard-line no-tax conservatives still pin hopes on “non-tax revenueâ€â€”lottery money, state fines and fees, and return on state investments. The comptroller’s office estimated non-tax revenues would hit $7.8 billion in the next biennium. That’s hardly chump change, but you’d have to be stupid to rely on it as a major source of school funding. None of these revenue sources will keep pace with the rising costs of education. Lottery earnings are notorious for flagging over time, as lottery players get bored and discouraged.

The state’s over-all investment earnings are expected to decline over the next biennium. And really, there’s only so much you can charge for a hunting license. So new taxes have to be considered, as even the governor and lieutenant governor concede, but it’s a delicate subject for elected officials to broach. Even under restructuring that is technically “revenue neutralâ€â€”no net gain of money for the state—somebody will pay more than they were paying before. That possibility is giving the business community a bad case of nerves. Reportedly, vicious in-fighting is breaking out in the business lobby, as every sector tries to make sure somebody else gets soaked for the money.

“The lobby isn’t interested in sitting down and talking about solutions—they’re interested in making sure they aren’t the ones who get taxed,†says one lobby insider. “Everybody circles the wagons and tries to protect what they have. The lobby will sit and watch everybody else get thrown to the dogs.â€

And where there’s no consensus among the business lobby, cynics say, consensus among state leadership will be a long way off. Take the closing of the “Delaware sub†loophole. The Delaware sub is a shining example of a shady tax scheme, and its abuses are notorious. It works something like this: Corporations enjoy favored status, and are accorded state services, like legal protections and access to the courts, that other businesses don’t enjoy. The state taxes corporations on the theory that they ought to pay part of the costs of those services. Since unincorporated businesses don’t receive those services, Texas excuses them from the tax. The loophole has proved to be an open invitation for abuse. Businesses operating in Texas incorporate in other states—Delaware, famously—with low or non-existent corporate taxes. They then form partnerships in Texas, which funnel the profits to the parent corporation. The Comptroller’s office estimates the state lost nearly $250 million through the loophole last year, and expects that those losses will pick up as more businesses restructure to take advantage of the loophole.

The governor estimated those losses somewhat higher when stumping for the closing of the loophole last January. But the Delaware loophole has powerful supporters, including computer giant Dell, the HEB grocery chain, and insurance provider USAA Inc. Lobbyists for these interests and others have undertaken a massive offensive to keep the loophole in place. The governor still supports closing the loophole, Walt says. Everyone does. You just don’t hear much about it any more. (Lately, the governor’s aides seem to be on a non-tax revenue tack, churning out proposals for video gambling terminals, state-taxed casinos on Indian reservations, a dip into the state’s cash reserves, and another billion-dollar round of budget cuts to other state services.)

The governor’s office has also floated a split property tax, levying one rate on individual property owners and another on business property. While this plan doesn’t address the schools’ over-reliance on property tax, it would allow the state to offer the majority of voters a lower tax rate, at the expense of business. Whatever their other disagreements on tax reform, horrified business leaders are united against the split.

“We think it’s an absolutely terrible idea,†says Bill Allaway, president of the Texas Taxpayers and Research Association, a pro-business tax policy think-tank. “I think the one thing on which there is a significant consensus is that business doesn’t think is strictly a business issue.â€

That’s about as close as the business community will come to publicly supporting something like a statewide income tax. (Support would be “quite a public relations issue†says TTARA school finance analyst Sheryl Pace.) But privately, acceptance in the business community for an income tax on individuals may be much broader. In a strange twist, this would make allies out of the fiscally conservative TTARA and the fiscally liberal Center for Public Policy Priorities.

CPPP has been pushing the idea of a state income tax on the school finance committee since last summer, pointing out that a moderate income tax that provided for property tax relief would have most Texans paying less than they do now. Notwithstanding, the committee met CPPP economist Dick Lavine’s income tax proposal last July with coughs and paper rustling. Fear of such a proposal runs deep at the Lege, where support for an income tax seems to fall somewhere just short of “letting the terrorists win.†Despite the results of a Scripps-Howard poll showing 52 percent of Texans would support an income tax if the revenue were split between property tax relief and education, state leaders from the governor on down have fallen over each other to voice their opposition.

With no solid promise of new money, the Joint Committee on Public School Finance is still fantasizing about a way to get more by spending less. Stanford economist Eric Hanushek gave the committee the glad tidings that money spent locally improves schools, but money spent at the state level mysteriously has no measurable effect. Hanushek also spent hours persuading the Subcommittee on Cost Adjustments that putting more money into education is folly, and that class-size reductions have no effect on student performance. Whether smaller classes improve learning is a hotly contested issue in educational research—in fact, a re-analysis of one of Hanushek’s own studies by Princeton researcher Alan Krueger purported to show they do—but the committee didn’t bother to call any witnesses to counter Hanushek’s testimony.

Education consultant John Schachter, formerly of the Milken Family Foundation, told the Subcommittee on Benefits and Compensation that teachers’ experience and education are irrelevant to students’ learning, and recommended that the state base teachers’ pay on the TAKS scores of their students. While most teachers’ groups support extra pay for improved performance, they say standardized test scores are too narrow to be the sole measure of improvement—an opposition that Schachter called “a Teamster mentality.â€

Chairman Grusendorf himself brightened visibly at a subcommittee hearing where, for an all-too-brief moment, data appeared to show that there was no correlation between district property wealth and district performance. No, explained Paul Corbet, a school finance consultant and former member of the House, that wasn’t what the data indicated at all. What the study showed was that property wealth doesn’t determine student performance—because the Robin Hood system has successfully equalized spending between rich and poor districts.

“Money matters,†Corbet told the committee. “Districts that spend more do better. If you want an exemplary ed

cation for each of

these students you’re just going to have to provide more.†There was a glum silence as the committee let that sink in.

Of course, one way to make the numbers come out even is to cheat. And one way to have good schools for less money is to readjust the idea of what constitutes a “good†school. Or make that an “adequate†school. Last May, in West Orange-Cove vs. Alanis, a lawsuit brought by property-wealthy districts to challenge Robin Hood, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the Legislature could satisfy their constitutional obligation to provide a “general diffusion of knowledge†with something short of complete equity. In the Supreme Court’s opinion, as long as every student in the state receives an “adequate†education, state spending on each child need not be equal. As long as students in poor districts are adequately educated, rich districts can keep their tax money. That decision sent lawmakers in a headlong rush to define an “adequate†education.

So the House hired Dr. Lori Taylor, an economist with the Dallas Federal Reserve, to conduct a statewide “adequacy study.†Seventeen other states have conducted adequacy studies of their most successful schools to determine whether they were spending enough on education. Almost all found they needed to spend more. Unlike those studies, however, Taylor and her team of researchers won’t put a price tag on “adequate†education. Instead, their study uses a statistical approach to associate increases in graduation rates, test scores, college enrollment, and other outcomes, with different levels of spending.

“We’re not going to tell them, ‘It costs this much,’†Taylor says. “The Legislature will decide what they consider adequate and what level of funding that translates to.†Conversely, the Legislature could decide how much it wants to spend, and define the outcomes as “adequate.†Poor districts fear they will do exactly that. But the low-balling of education isn’t the only problem with the study. A single definition of adequacy suggests a “one size fits all†conception of education that doesn’t sit well with many educators. Moreover, the Legislature is expected to seek a definition of adequacy that closely mirrors the state’s accountability system; this leaves arts, civics, and athletics—which fall outside the state’s standardized testing system—out of consideration. It could also push aside students who don’t fall within the testing system. Some special education students are exempt from the TAKS, taking an exam at a lower grade level, or an alternative exam that is not averaged into their schools’ accountability ratings. Special education advocates are wary that the adequacy approach could divert funds from these kids.

“In tight times, the funds get spent on those students that you get held responsible for,†Kay Lambert of Advocacy, Inc. told the Joint Committee. “The money is going to go to the kids who are held accountable.â€

Another piece of creative bookkeeping would readjust the amounts the state spends on select groups, like special education, bilingual, and economically disadvantaged students. The state’s Weighted Average Daily Attendance (WADA) system gives districts an additional share of money for each child who is more expensive to educate. In the name of “simplification,†some legislators have suggested changes to the WADA system. One of the most popular proposals would collapse the weights for bilingual and economically disadvantaged students—assigning a single weight for both groups. Aside from the rather startling implication that all poor kids come from somewhere else, this would be a serious funding cut to urban districts like Houston and Dallas, which educate both poor Anglos and middle-class bilingual kids. If the Legislature can’t muster the political will to raise new money, this kind of fancy number crunching will make casualties of hundreds of thousands of Texas children. The poor, minorities, and the learning disabled may feel the pinch first, but in the end nearly all will suffer, as the number of students grows and the money dwindles.

“You will have the very finest schools set aside for a few,†says Wayne Pierce of the Equity Center, an advocacy group for property-poor school districts. “The rest won’t be able to compete.â€

Gutting the schools will cost all of us eventually. Corporate boosters and fiscal conservatives threaten that taxes will harm the “business climate†of the state; they ignore the reality that a populace of the uneducated and unemployable does not a healthy economy make. Here’s a grim statistic for you: If current trends continue, state demographer Steve Murdoch projects that the average family income will decline. By 2020 nearly one million Texas families, or about 13 percent, will live in poverty.

Sooner or later, legislators will have to decide between their school districts, their property owners, and their friends in the business community. And if the Governor calls a special session this spring, it will be a very public decision indeed. It’s not surprising elected officials do a duck-and-shuffle every time the subject of how to pay for the schools hits the table. Surely, some legislators must be thinking in their heart of hearts, if they ignore the schools long enough, they will just go away.

Emily Pyle is a freelance writer based in Austin. Support for this article was provided by the Observer’s Maury Maverick Jr. Fund for Cantankerous Journalism.