Unhealthy Forests

After a 15-year reprieve, East Texas forests are once again open to destructive logging

Driving east on T. F. Boulware Road, inside the boundaries of the Angelina National Forest, the woods differ dramatically depending on where you stop the car. Immediately after entering the National Forest, hundreds of pines of the same species, size, and straightness stand a regular distance from one another. There is little discrepancy in the view. Like uniform lines on wallpaper, few fallen trees or bended hardwoods interfere with the perfect vertical pattern.

Bordering the stand further to the east, however, the natural world is teeming with diversity. A weatherworn tree cavity, slowly being devoured by turkey tail fungi, leans precariously about 30 feet up. Two types of pine, loblolly and short leaf, are present in this stand, all of varying heights and girths. Southern red oak and sweet gum grow between the pines. Some areas of view are dense with crowded tree trunks, others open enough for the light to fall on the understory of shrubs and small hardwoods.

A third of the Texas National Forests looks like what they were planted to be—tree farms. Boulware Road is a good vantage point to see both a wilderness area and stands of wood that closely resemble pine tree plantations. The wilderness area, called Upland Isle, is managed for wildlife. The symmetric stands of trees west of it have been managed for timber production. In the story of commercial logging on East Texas public lands, the view from Boulware Road may be the only straightforward one around.

The battle over which of these two tracts off of Boulware Road constitute a healthy forest has only just begun. Environmentalists are concerned that new policy changes in forest management, courtesy of the Bush Administration and the federal courts, are about to open Texas National Forests to massive logging not seen in more than a decade. Wildfire legislation and the lifting of court-imposed bans, allows the National Forest Service to circumvent environmental laws previously relied upon by conservationists. Even worse, environmentalists say, is that official rhetoric couches logging as a boon to forest health and the preservation of a key endangered species.

The extensive logging environmentalists fear has a long history in the National Forests of East Texas. Land for four Texas National Forests was purchased by the federal government in 1934: the Angelina, Davy Crockett, Sabine, and Sam Houston. The majority of the land was previously owned and logged by timber companies. But feeling the effects of the Depression and further burdened by taxes on property already stripped of its valuable trees, the industry agreed to sell some of its land. At that time, the national forests were intended to supply American timber markets in the event that private resources became exhausted. A small percentage of the National Forests in Texas were replanted; the vast majority regenerated on their own. Starting in the 1960s, as trees grew to marketable size, clear cutting became big business in the public forests of East Texas. But the biological damage brought on by clear-cutting techniques created a national outcry. Spurred by the environmental movement and concern over the dwindling amount of natural spaces left in the United States, public attitudes toward the national forests began to shift toward conservation. The agency that runs the forests, however, was founded on the principle of timber production, and since the 1960s, 30 percent of Texas forests have been clear cut and replanted, resulting in monoculture stands of pine trees.

For the last 15 years, environmentalists have been successful at keeping loggers out of a large portion of the Texas National Forests. In 1988, organizations dedicated to protecting an endangered woodpecker attained a tenuous status quo, via court injunction, that minimized clear cutting on almost half of East Texas’ National Forests. In the decade following the injunction, logging on National Forests in Texas dropped by 90 percent.

But the future of Texas forests may soon emulate the uniform pines found on Boulware Road. A recent court decision and the Bush Administration’s deceptively named Healthy Forests Initiative create a culture of forest management that favors timber company handouts and limits public involvement. The result, conservationists fear, will be distinctly unhealthy Texas National Forests.

In July of this year, a federal district court based in Lufkin lifted the moratorium it had placed on commercial timber sales more than a decade ago. The injunction, which extended to the 40 percent of Texas public forests inhabited by red-cockaded woodpeckers, resulted from a lawsuit alleging that the National Forest Service was in violation of the Endangered Species Act. The court found that commercial clear cutting in the Texas National Forests was hastening the population decline of the endangered woodpecker. This past summer, however, the court accepted a new plan put forth by the Forest Service that promises to shape the forest into ideal woodpecker habitat. Since the new red-cockaded woodpecker management plan allows commercial timber sales and variations on clear-cutting techniques, East Texas environmentalists fear that the Forest Service’s newfound affinity for the woodpecker is no more than cover for a covert logging operation.

A year before the court lifted its injunction, and thousands of miles away, several western states faced what has become an almost annual bout of severe forest fires. In the summer of 2002, amidst a backdrop of six million charred acres, President Bush revealed his Healthy Forests Initiative. The Administration describes it as an efficient new way to protect local communities from wildfires by reducing ignitable pine needles, shrubs, and dead limbs that cover the ground in the National Forests. Environmental advocacy groups have replaced the word “Healthy” with

“Stealthy” to describe their take on Bush’s initiative. They consider it a huge giveaway to the timber industry that will have no effect on communities facing a fire threat.

Following the president’s 2002 announcement, Congressman Scott McInnis (R-Colo.) introduced House Resolution 1904 to make the president’s plan law and Bush issued an executive order for Healthy Forest Initiative Pilot Projects to begin. Ten test sites were chosen nationwide to implement the new “streamlined” Forest Service policy and create a model of efficient “fuel reduction.” One of the pilot projects is in the Boswell Creek Watershed of the Sam Houston National Forest, about 10 miles southeast of Huntsville, Texas. (Last month, on November 21, Congress approved Bush’s initiative.) Between the court decision to lift the clear-cutting moratorium and the local pilot project, Texas conservationists are scrambling. Their task is to combat policy changes that both nullify their past work and that leave them impotent to challenge future logging. “Basically, it is open season on public forest land,” says Brandt Mannchen, Forest Task Force chair for the Houston Sierra Club.

The red-cockaded woodpecker is about eight and one half inches in length, with a black-and-white barred back and white cheek patch. Two red tufts, although rarely visible, adorn the adult male’s head. The beauty of the red-cockaded woodpecker is not in his plumage, but in the painstaking architecture of his home. The bird requires open, mature pine or pine-oak woodland habitat. Its nesting cavity is laboriously pecked out of a large living pine tree that has succumbed to heartwood disease. Once the cavity is bored (a process that takes between one and six years), the woodpecker drills tiny holes around the opening, causing pine pitch to flow from the sapwood layer and coat the tree trunk. The result is a greased-pole security system to prevent egg-snatching and other predator mischief. Each colony requires about 120 forest acres, and generations have been known to use the same nesting cavity. The female Picoides borealis is a wanderer though, keeping the gene pool from becoming stagnant. With habitat loss and fragmentation, the red-cockaded woodpecker’s numbers have continued to decline since it was first listed as endangered in 1972. Once living as far north as New Jersey, it is now rarely sighted outside of the Gulf Coast states. The forests of East Texas mark the red-cockaded woodpecker’s most western range.

For years, the endangered woodpecker served as conservationists’ rallying point in their battle against East Texas logging. Now it appears that federal agencies have learned how to use an endangered species to their advantage as well. They have crafted a forest strategy that purports to cater to the red-cockaded woodpecker’s best interests, but includes practices strikingly similar to a plan for tree farming. Both management plans call for limiting hardwoods, pine spacing, and a frequent burn schedule. Environmentalists are suspicious that the Forest Service’s new red-cockaded woodpecker management policy is simply a guise to continue logging within the law.

“They are essentially running a commercial timber operation but still providing for the red-cockaded woodpecker,” says Mannchen, of the Sierra Club. He adds that the habitat created by the Forest Service isn’t necessarily the bird’s natural niche, it is just one in which the woodpecker can exist.

Texas conservationists are particularly concerned that under the Boswell Creek Watershed pilot project, hardwood trees that produce nuts and berries will be removed from the forest. Hardwoods typically grow beneath the pine canopy, in the level called the midstory. In the past, hardwoods such as southern magnolia and dogwood were killed or removed in order to encourage young pine growth. Under the Forest Service’s red-cockaded woodpecker plan, they can be removed to provide a more open, park-like habitat for the woodpecker.

This wouldn’t be the only example of the government logging national forests under a pretext. The Healthy Forest Initiative itself is supposedly a response to fuel buildup on public lands. But the Sierra Club argues that Bush’s forest plan serves to increase logging in the backcountry, miles from any homes or neighborhoods. And the McInnis bill supplies few funds for fuel reduction in the area 500 feet around houses and other buildings—a tract of land aptly dubbed the Community Protection Zone.

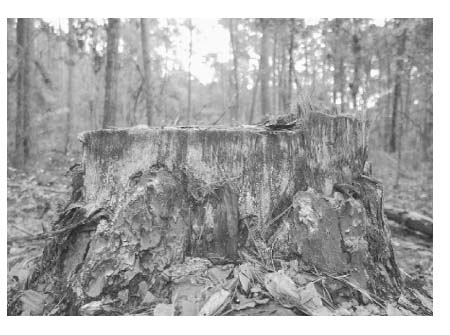

The fire debate may very well be a moot point in Texas anyway. Unlike in the western states, the wooded areas north and northeast of Houston don’t flare up every summer. Although several subdivisions neighbor the pilot project in Boswell Creek Watershed, it isn’t packaged in fire scenario language. It is promoted as risk reduction for the imminent threat posed by the southern pine beetle. Ironically, the majority of trees planted by the Forest Service after clear-cut operations were loblollies, the least resistant of the native pines to both fire and southern pine beetle.hris Wilhite, a conservation organizer for the Sierra Club, walks with a quick pace along the Lone Star Hiking Trail in the Sam Houston National Forest. He stops in a section of forest identified by the government as “compartment 76.” Severed branches, or slash, litter the forest floor, and large stumps reflect beams of sunlight that, until recently, were not able to penetrate through the canopy. The widest stump measures about 32 inches in diameter; another is 26 inches. Tree ages could have been anywhere from 50 to 80 years. Wilhite searches further and points out the damaged bark of a nearby hardwood tree. It had the misfortune to serve as a pivot point while the felled pines were dragged through the remaining stand of forest. The scene is by no means a clear cut. According to the Forest Service, it was a thinning operation done to improve wildlife habitat and had nothing to do with making money. Yet the feeling is reminiscent of exploring a historic cemetery. The more you wander, the more gravestones you find. “We agree with the Forest Service that management needs to be done. We disagree with the way they’re going to do it,” Wilhite says.

Most environmentalists are not opposed to selective thinning or scheduled burns in the National Forests. It is the level of intensity that mainstream conservationists question. Based on what they consider the Forest Service’s abysmal track record in Texas and the inherent contradiction of using the logging industry as caretakers of the forest, conservationists have no reason to trust a management plan that is not strictly limited by a court.

The Boswell Creek Watershed had a history of controversy even before it was chosen to be a Healthy Forest Initiative testing ground. Within the watershed is a section of land called Four Notch. Twenty years ago, Four Notch was included on a list of proposed wilderness areas by Texas conservation groups. While being studied for designation, Four Notch underwent a southern pine beetle infestation. The Forest Service announced plans to cut breaks in the area to prevent the insects’ spread. Conservationists, fearful that severe logging would disqualify Four Notch for elevated wilderness status, appealed the decision. Their appeal was denied and a massive salvage logging operation ensued. Despite a day of protesters chaining themselves to trees, large swathes of land were clear cut, and the marketable logs were removed from Four Notch.

Typically, a clear cut is followed by site preparation, which consists of killing and burning the remaining forest so that a new crop of pines can be planted without competition. Horror stories still circulate among conservationists describing the methods of site preparation used in the Four Notch area. A “tree crusher” with self-propelling blades indiscriminately hacked away everything in its path. A bulldozer equipped with a triangular sheer blade attachment plowed smaller trees, limbs, and shrubs into piles of organic refuse. Finally a helicopter flew over the area and simultaneously released and ignited alumagel, a congealed gasoline product akin to napalm.

Larry Shelton, an environmental activist, surveyed the area after the helitorch “dropped fire from the sky,” and reports that he found scorched armadillo carcasses and turtle shells among the ashes. Four Notch was transformed into a wasteland rather than a wilderness. The fact that this same area is now a national pilot project to exemplify the “Healthy Forests Initiative” is ironic. To environmentalists, it signifies a celebration of destructive forest policies.

Roughly half of the stripped land in Four Notch was replanted, and just like rows of carrots sown in a garden, the young pines were put in with the assumption that regular thinning would follow. The physical result of the clear cut is that a majority of Four Notch consists of densely packed trees that haven’t yet reached a marketable age.

In order to pay for thinning projects, larger trees with monetary value will be sacrificed. The Forest Service plans on reducing the tree mass on most acres by 10 to 50 percent. Opponents of the pilot project say that using a “Goods for Service” funding mechanism encourages the logging of older, more fire-resistant and valuable trees. This seeming conflict of interest is what the Sierra Club’s Wilhite identifies as a main problem with management under Bush’s forest initiative. Environmental groups want the government to stop subsidizing logging operations and instead use the funds to pay for the thinning of smaller, unmarketable trees. Citing erosion and habitat destruction, they also call for an end to clear cutting and “even-aged logging,” the public relations name given to clear-cutting variations. Wilhite reasons that using the timber industry as a management tool encourages mismanagement and costs money as well.

The economic rationale of logging national forests has been questioned by environmental organizations for years. Texas groups

argue that contrary to Forest Service records, logging p

blic lands is a money-losing operation. A 2002 report by the Ecology and Law Institute on the hidden costs of logging Texas National Forests found that between 1987 and 1999 taxpayers lost $26 to $32 million.

According to researchers with Texas A&M University, timber is the third most valuable agricultural commodity in the state. Yet the Ecology and Law Institute states that the four National Forests account for only 2 percent of the productive timberland in Texas.

Historically, logging on national forests provided much-needed revenue for the counties that encompass the public land. Thus a huge financial incentive (25 percent of each year’s lumber profits) existed for local communities to support contract logging in the National Forests. Thanks to the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000, counties may opt instead to receive regular payments directly from the government. The Clinton-era law assures future payments comparable to those received in the most profitable logging years between 1986 and 1999, even if current timber sales on national forest property plummet.

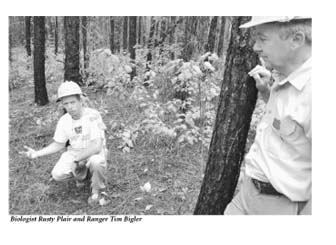

t is October 10th, the last day for public comment on the Forest Service’s Environmental Assessment of the Boswell Creek Watershed Healthy Forest Initiative Pilot Project. District Ranger Tim Bigler and wildlife biologist Rusty Plair drive a Ford F-150 from the Sam Houston National Forest’s New Waverly office into Four Notch. They are not physically far from the stumps located by Wilhite, yet their perspective on forest management is light years away from his point of view.

Both men appear to fit their respective job titles. Bigler, who has been with the U.S. Forest Service since 1978, has a calm administrative confidence and a meticulously clean uniform. His salt and pepper hair is neatly trimmed, and his voice varies only moderately in either pitch or volume. Plair, who specializes in red-cockaded woodpecker management, wears a non-government-issue t-shirt, tucked in, that reads, “nothing runs like a Deere.”

As the truck dips and bounces on the dirt road, the two men discuss how the Forest Service attitude toward management has changed in the last few decades. “When I began with the organization 25 years ago we were growing lumber and pulp wood to supply the American markets. We did a lot of regeneration just for that…wildlife was secondary, but that is not the way it is anymore,” Bigler explains.

With the passage of federal legislation like the Endangered Species Act and National Forest Management Act, the Forest Service risks violating laws if it practices environmentally destructive logging on public lands. Bigler points out that the easiest way for environmentalists to shut down the Forest Service’s pilot project would be to find it out of compliance with regulatory guidelines. Reason enough, he says, for the agency to obey the law. “They know how to get an injunction,” he sighs, “they’ve done it before.”

The ranger says it wasn’t difficult for him to shift focus during his career from producing trees to producing wildlife habitat suitable for the red-cockaded woodpecker. “If we want to grow woodpeckers, we grow woodpeckers. If we want to grow trees, we grow trees. We can do whatever they tell us to do—focus on timber, focus on wildlife, focus on protecting neighbors from fire,” he says.

Bigler reasons that the Healthy Forest pilot project will serve three distinct purposes: to increase woodpecker habitat, encourage forest resistance to southern pine beetle attack, and minimize wildfire risk to neighboring communities. Yet because the logging and burning treatments used to achieve these three goals are similar to the tools employed during decades of pine monoculture, Texas environmentalists wonder if forest management hasn’t simply returned to its old ways under a new name. This time around, they argue, an endangered bird and fears of insects and fire are masking policy that might otherwise be sharply scrutinized.

Plair leans up from the back seat of the cab and admits that creating red-cockaded woodpecker habitat also means managing for southern pine. “Because the red-cockaded woodpecker is tied to a commercially valuable tree, some people think that when we refer to removing midstory and hardwood, cutting in general, they think we’re producing a pine monoculture—trying to convert to all pine. But the objective is to create habitat,” says Plair, obviously frustrated by the interpretation that timber sales are still a priority in the Sam Houston National Forest.

Both Forest Service employees acknowledge that logging is controversial. Yet, in step with the Bush Administration’s spin, they firmly believe that the point is not to sell timber, but rather to use timber sales as a method to manage the ecosystem. And with the federal government’s allocation of $362 million in tax dollars to administer commercial logging in U.S. National Forests in 2002, timber contracts probably are the most attractive way for district offices to do their work. Because their implementation costs are already budgeted, logging contracts provide an easy way to reach thinning goals. In addition, the Forest Service can ignore the cost of related activities, such as road building and road removal, and report a financial profit from the sale. Congressman McInnis’ Healthy Forest bill will encourage even more logging contracts and may result in increased federal subsidies for timber sales on public lands.ush’s vision of public participation in the management of public lands seems to be that there shouldn’t be any. The genius of his forest initiative is not only that it allows private companies to increase logging National Forests under a smokescreen of wildfire protection, but that it strips the public of recourse to challenge the timber harvesting contracts. This is not surprising considering President Bush’s appointment of Mark Rey as the undersecretary for natural resources and environment. From his position within the Department of Agriculture, Rey oversees the Forest Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service. Before becoming a public servant entrusted with the preservation of America’s natural heritage, Rey worked for the American Forest and Paper Association and the American Forest Resource Alliance. While a timber industry lobbyist, he pushed to get rid of the public’s right to appeal logging contracts and campaigned against the Endangered Species Act, arguing that it unfairly restricted business. As undersecretary, Rey is finally making his lobbying goals a reality.

One of his long-time efforts is to limit the avenues of public participation available to environmentalists. In the past, Texans have effectively used the National Forest Service process of citizen comment and appeals to build evidentiary records admissible in future litigation. The 1988 lawsuit to protect the red-cockaded woodpecker, for example, included citizen data collected to appeal Forest Service timber contracts. After the appeals were denied, conservationists used some of the same evidence already on record in the subsequent, and successful, lawsuit.

The Texas pilot project is meant to test an “improved and cleaner process on environmental assessments,” according to a Forest Service press release. In this case, “cleaner” means less review. Instead of requiring in-depth investigation of environmental impacts, Bush’s Council on Environmental Quality issued new guidelines instructing National Forest district offices how to prepare a brief 10- to 15-page document demonstrating compliance with federal law in the absence of a rigorous Environmental Impact Statement. As environmentalists expected, the Forest Service issued a draft “Finding of No Significant Impact” in regard to the Boswell Creek Watershed Pilot Project.

“I don’t see how it can not be a significant impact to log 4,000 acres and burn 8,000,” says Mannchen of the Sierra Club. He warns that with the passage of the Healthy Forest bill, almost anything the Forest Service does with respect to logging can be called “hazard reduction” and excluded from the public appeals process. Mannchen is pessimistic that the Forest Service will address taxpayer concerns at all, “and if they do talk to the public, it will be a mere formality.”

Legally, McInnis’ forest bill does more than trample the rights of Americans to appeal actions by their government. According to a statement issued by U.S. Rep. Nick Rahall (D-W.Va.), a ranking member of the House Committee on Resources, it also “represents an unprecedented assault on our judicial system.” A dozen civil and workers rights organizations, including the NAACP and the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees, are distressed by the judicial review provisions contained in HR 1904.

The legislation is troublesome for two reasons, they say. First, the bill may force some federal courts to prioritize lawsuits regarding timber projects ahead of other pending cases, including those that involve civil and workers rights. Secondly, the legislation would require courts to favor the Forest Service when conservationists request an injunction to stop logging or burning. Civil rights groups argue that giving a federal agency greater weight changes the fundamental balance of the American legal system.

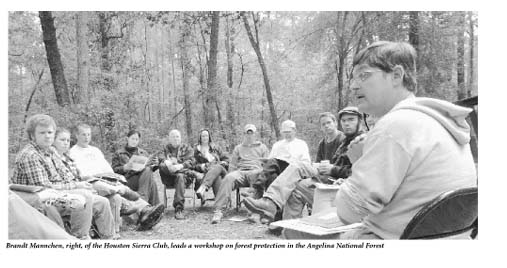

Despite the legal ramifications of HR 1904, Texas environmental organizations are preparing for the full effect of Bush’s forest policy by educating and reaching out to the people it will affect the most—the taxpaying public who own the land. As part of the movement to combat the Healthy Forests Initiative, two-dozen Forest Watch participants gathered at Boykin Springs Recreation Area of the Angelina Forest on the weekend of November 7. The activists, while not diverse in ethnicity, came from a variety of Texas cities—Dallas, Austin, Houston, nearby Woodville, and Lufkin—with the hope of protecting public forests. Sponsored by the environmental advocacy groups the Sierra Club, the Texas Committee on Natural Resources (TCONR), and SACRED Redwood, the Texas Forest Watch Weekend acquainted volunteers with methods used to challenge unsound timber sales and other questionable projects in the National Forests. The weekend was spent in workshops learning field techniques, legal documentation, and natural science. “We’re going to have to start watching the forests again,” said Cliff Rushing, a workshop participant and the Forest Issues Coordinator with the Dallas Sierra Club.he word loblolly rolls around inside one’s mouth and turns a few cartwheels under the tongue before tumbling out. Just saying it forces the jaws and lips into gymnastics required by few other words. But Larry Shelton, a long-time resident of the pineywoods and a trustee of TCONR, pronounces loblolly with perfect Mary Lou Retton-style execution. He’s been saying it, working with it, and learning about it for years. Shelton, now 46, began carpentry at age 19. He hand-built his own house in Nacogdoches from East Texas wood, and supports himself by cabinet making. It is his business to know timber, and he has made it his business to know timber production. Like most Texans interested in protecting the National Forests, he isn’t your stereotypical tree-hugger.

With a thin plaid shirt clinging to his 6-foot-3 frame from the steady afternoon drizzle, Shelton points out the structural diversity in the Angelina Forest’s Upland Isle Wilderness Area just off Boulware Road. There are snags that provide perches for raptors, shrubs growing chest-high, and gradual variations in forest density. Although there is no logging in the wilderness area, every aspect of the ecosystem is functional, including naturally felled pines.

“A tree serves a useful purpose from the time it starts growing until it goes back to the earth,” Shelton says.

The natural cycle of life, death, and decay is clearly illustrated in Upland Isle. But these characteristics are absent from the neighboring 15- to 20-year-old pine plantation, where the loblolly stand is in an artificially arrested state. The monoculture trees “are only economically healthy,” Shelton says, “they aren’t healthy for wildlife.”

What signifies a healthy forest has been debated for more than 40 years, but recently the discussion has become more convoluted and less balanced. Environmentalists no longer have a monopoly-like grip on using endangered species to their advantage. And the government has created loopholes to exclude itself from landmark conservation laws. Few forests illustrate this shift in power toward logging interests better than the pineywoods of East Texas. To long-time environmentalist Larry Shelton the new policies signify a dangerous moment in the history of the Texas National Forests. With many of the legal safeguards protecting Texas National Forests effectively axed, the forests themselves may soon fall under the blade.

“They will sell timber through any avenue they can,” he says.

Amber Novak is an Austin-based freelance writer and photographer.