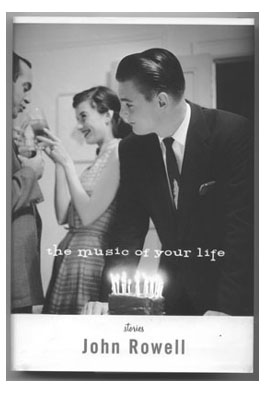

Music Man

by Diana Anhalt

At a workshop I attended this past January, poet Alfred Corn asked us to recite lines we’d memorized as children: “These become internalized,” he told us. “They determine the sound and cadence of everything you write.”

If New York film critic and former actor John Rowell, author of The Music of Your Life, had been a workshop participant, he would, I believe, have recited song lyrics—Rogers and Hammerstein, Cole Porter, and Steven Sondheim—for starters. Then, he’d have moved on to the plays: Noel Coward or Tennessee Williams with, no doubt, a few movie exit lines thrown in for good measure. They are the music of his life. They determine not only the sound, but to a great extent, the content of the seven distressing, yet simultaneously comic and skillfully wrought short stories included in this, his first collection.

While each of these stories can stand on its own, they are, nonetheless, linked, not only by their allusions to show biz, television, music, and films, but by their southern flavor and uncanny attention to detail—Eudora Welty and Truman Capote influenced Rowell early on.

All the protagonists are gay men, often children or adolescents, raised during the 1950s or ’60s in hostile environments—small towns, generally in North Carolina, that are populated by well-intentioned bigots. At some point in their lives, Rowell’s characters struggle to discover and cope with their sexual identities and—far more important—their personal identities. They distance themselves physically, by leaving their homes, and mentally, by retreating into fantasy worlds of their own making. In so doing, they become spectators gazing wide-eyed as their lives unreel before them. (This collection could well have been entitled The Theater of Your Life.)

The title story deals with a 10-year-old who survives the “cruel barren wilderness” (of the playground) by creating his own land of make-believe, fueled by television’s Lawrence Welk, Mister Music Maker. “The Lawrence Welk Show” introduces him to the heady glamour of Broadway and reassures him. “‘Yes,” he says. “There really is a world filled with celebrities and music, ‘champagne ladies,’ dancing shoes, diaphanous ball gowns and places like Paris…” But when Ray, his father, grows bored with “the girl shows,” and switches channels, there’s always “Batman,” with its disturbing images of beautiful men in tights engaged in rough-and-tumble feats, allowing the boy to indulge in forbidden fancies:

Watching Batman with Ray, you maintain a blank face so he won’t see how you really feel about it. It’s an acting exercise, this art of making your face Go Blank at key moments, and you’ve mastered it… Go Blank, and no one will know whose side you’re on. Go Blank, and you can be as neutral as Switzerland. Go Blank, and you won’t make enemies within your own family.

Although the men in Rowell’s stories view their lives from a distance, the reader can’t help empathizing with them. Their conflicts are universal, and the protagonists are portrayed with honesty, humor, compassion, and insight. At times, we feel closer to them than they do to themselves.

Take the aptly named Hunter, for example, the main character in “Spectators in Love,” a long short story that, likes several others in this volume, comes close to being a novella. As a five-year-old, Hunter carries around his recording of Mary Poppins while others his age still cling to a favorite blanket or a stuffed animal. In time, his universe is circumscribed by music and films and by a few isolated relationships with peers who share his interests. The relationships don’t survive, but his overriding passions do. At one point he confesses:

My mother narrates stories of my childhood to me so often that I have begun to feel that the little boy she talks about is not actually me, but some role I played. Sometimes, it seems that I had nothing to do with my own early years at all, that instead I am sitting in a dark theater watching some other child actor play me up on the screen. I watch him enacting events in my life far better than I ever could have…

This sense of detachment is particularly heightened in the title story, “The Music of Your Life,” through the author’s skillful use of perspective. Here, rather than employing the more conventional first person “I” or the third person “he” or “she,” Rowell resorts to the less frequent second person, referring to his characters as “you.” “You’re ten years old. It’s summertime. And you have Lawrence Welk damage.”

A more personal approach, the second person gives the story a far more intimate feel than it might ordinarily have. It conveys the sense of a voyeur passing judgement on the characters, much as the characters pass judgement on themselves.

Using this perspective also allows Rowell to shift back and forth between two points of view, in this case, the child’s and his father’s. He pans in first on one, then on the other. Much as a photographer shifts camera angles, the writer shifts points of view.

Rowell’s techniques are, in part, borrowed from the very films he writes about. He changes locales, travels back and forth in time, focuses on one character, as in a close-up, retreats, and then zooms in on another. These techniques focus, as well, on our role as readers. Ironically, we—like his characters—also become spectators.

Irony is at the center of each of these stories and their interest and humor lies, to a great extent, in Rowell’s ability to employ it so effectively. In “Saviors,” the shortest story in the collection, a well-meaning aunt, oblivious to her choir director’s sexual identity, insists on arranging a meeting between him and her divorced niece. (Their names, Bitsy and Burton sound so “right” together.) Incapable of recognizing her mistake, she utters the final words in the story: “Thanks be to Her. She has saved them. Alleluia.” Oddly enough, due to a series of unexpected coincidences, that’s precisely what happens. The story ends with the promise of salvation, but of a sort that Aunt Jean would never understand.

Misunderstanding underscores much of the humor here, as well, particularly in relation to sexual identity: “The only person who knows I’m a boy is Lucille Ball,” the narrator of “Who Loves You?” tells us.

As a boy I have to keep adjusting under this dress I’ve got on so I can feel myself down there, just to remind myself. I’ve never worn an evening gown before, and it’s the oddest thing. Not to mention that I can barely see out of these stupid false eyelashes. Why on earth I ever agreed to be a showgirl, I’ll never know…

But we soon find out. Will, a wannabe actor, is eager to break into show biz. He believes that if he goes along with Ball’s scheme, she may offer him a juicier role further on. She wants to use Will to humiliate her husband, Desi Arnaz, a notorious womanizer. All goes according to plan: Desi is taken in by the disguise and makes a pass at Will, whom Lucille has introduced as Wilma. Ball catches him in the act and exposes Will’s true sex. But Desi isn’t the only one who is fooled. So is a gay showgirl. (She also propositions “Wilma.”)

Sexual ambiguity, though the source of much of the humor, is not a central concern here; choices made in the heat of the moment are. Looking back at his life from a vantage point of some 30 years, Will recalls his years in Hollywood and questions his behavior. In an attempt to justify, or at least understand it, he expresses the following sentiment: “It wasn’t like it was real or anything like that. It was just… we were just acting.”

At times, I felt as if Rowell were “just acting”— acting at being a writer. He occasionally uses stilted, over-clever dialogue, more appropriate for parody, and some of his characters are much alike, as if the same man had been captured in several locations playing an assortment of roles—the precocious child, an adolescent recuperating from a nervous breakdown, an actor, a film critic, a florist. In addition, he sometimes strains the imagination with grandiloquent and overblown language: For example, when the protagonist in “Spectators in Love” states: “here I am about to cry and my parents descend upon me from all corners like disciples rushing after Jesus upon news of the crucifixion,” I found it difficult to believe that a 13-year-old—no matter how good a Presbyterian— would be capable of such a metaphor.

But viewed from a distance, these are minor flaws in an otherwise impressive collection. The Music of Your Life provides readers with an additional lens through which to view contemporary society. It’s well written, gripping, amusing, and provocative.

Diana Anhalt is a poet and writer in Mexico City. She is the author of A Gathering of Fugitives: American Political Expatriates in Mexico 1948-1965 (Archer Books).