Gulf War Memoir Syndrome

by Elisabeth Piedmont-Marton

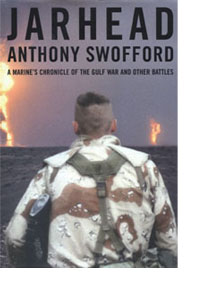

Jarhead: A Marines Chronicle of the Gulf War and Other BattlesBy Anthony Swofford

Baghdad Express

And so it is with a degree of cynicism—or marketing savvy—that we consider the phenomenon of two Gulf War memoirs released in the early days of the war in Iraq. (More accurately the war with Iraq, if you ask me, but you may want to ask the Secretary of Homeland Prepositions.) Gulf War and Iowa Writers’ Workshop veteran Anthony Swofford’s Jarhead was scheduled for an April 4 release, but as preparations for war escalated in the spring of 2003, Scribner’s moved the publication up by several weeks. On February 19, Michiko Kakutani raved in The New York Times, followed by Black Hawk Down author Mark Bowden’s breathless encomium on the front page of the Times Book Review. Then there were appearances on Public Radio International’s This American Life, and on television shows from Good Morning America to the Daily Show on Comedy Central where Swofford perfectly modeled his narrator’s rugged warrior-cum-sensitive-postmodern ironist persona. The result? After an initial printing of 50,000 copies, Publishers Weekly reported, Scribner’s went “back to press seven times in three weeks, bringing the total in print to 202,500 copies,” as of March 31. Although Jarhead garnered most of the ink, display space, and sales, Joel Turnipseed’s memoir of the same war was released in March from Borealis Press in Minnesota, and successfully caught a ride on Jarhead’s coattails for a while, but seems not to have been able to hold critics’ attention.

The buzz proved quite irresistible to me. I had been teaching the war memoir in a class on American literary responses to the Vietnam War and couldn’t wait to get my hands on both books. I bought them in hardcover and dug in. I read Jarhead first, liked parts of it a great deal, admired parts, but felt in the end skeptical and distrustful. I liked Turnipseed’s Baghdad Express better, but the more I thought about both books the more I became perplexed by the differences between my readings and the mainstream’s reviews and commentary. I’m not interested here in refuting the laudatory reviews, nor in trashing either book in reviews of my own. I’ll return to a discussion of Turnipseed’s book later, but for now I want to explore the reasons why critical response to Swofford’s Jarhead seems so skewed and hyperbolic, why it seems to participate more in a discourse of desire than a discourse of critique. Reviewers really need to love this book. And they want you to, as well. I tried to love it, but it’s simply not that good. Ultimately I found the narrative voice derivative and self-involved, and the style sometimes mannered and MFA-ish and sometimes gratuitously swaggering and crude.

Here’s Mark Bowden in the Times Book Review: “Rare is the marine who is willing to share the raw experience, and rarer still is the one like Swofford—the marine who can really write. Jarhead is some kind of classic, a bracing memoir of the 1991 Persian Gulf War that will go down with the best books ever written about military life.” And Kakutani calls Jarhead a “searing contribution to the literature of combat, a book that combines the black humor of Catch-22 with the savagery of Full Metal Jacket and the visceral detail of The Things They Carried.” And finally, John Gregory Dunne in The New York Review of Books: “Without war there would be no war stories, and Jarhead is one of the best—loopy, stoned, its prose like three heavy metal bands playing three separate songs at once. It honors the literature of men at arms.”

This kind of language had me checking the dust jacket to make sure I read the same book. What’s going on here? I think what’s happened is that the critical language has become embedded. Embedded in not just one, but two wars: the current war in Iraq, and the Vietnam War—not so much war per se, but as represented in the literature that the war produced. Embedded, of course, was a key term in representations of the war in Iraq when it was still called a war. One of the things we learned from observing that experiment is the same lesson we all should have gleaned from our freshman years in college: It’s not easy to embed someone without becoming emotionally involved. Laudably, reports from embedded reporters in Iraq were often disturbingly graphic and conveyed the chaos of battle, but they were more heavily mediated than they appeared, not just by military censors but more subtly by reporters’ quite human attachment to the units they traveled with and by their less visible desire to attach to themselves to the warrior virtues circulating about them.

I think the same dynamic is at work in the way critics read Jarhead. Critics read the current war in Iraq through narratives of the Gulf War, and in turn read these through the literature of the Vietnam War. These ecstatic and sometimes downright delusional reviews (“Swofford is never pretentious”) are rhetorical gestures that express a desire to contain the noises and images of unfamiliar wars within the contours of a familiar one. They seek to reassure us that war and death will offer at the very least the compensation of literature, that in the end discontinuity will become continuity, and chaos will become order. If only textually.

References to the literature of the Vietnam War are all over Swofford’s book—on dust jacket blurbs, in acknowledgements, and intertextual allusions and reviews make frequent and explicit comparisons as well. Dunne lists Philip Caputo, Tim O’Brien, William Broyles, Ron Kovic, Michael Herr, and James Webb as “very good writers wrote very good books about life under fire in a strange, faraway place,” company to which he welcomes Swofford. Bowden borrows O’Brien’s The Things They Carried as the title of his review. But is it legitimate to suggest that Swofford’s book belongs on the same shelf as these narratives of another war? Shouldn’t it be different somehow? Shouldn’t we expect that it do something more than, other than, the books to which it is heir?

The problem I have with Jarhead is that it wants to simply reproduce the Vietnam memoir by substituting desert for jungle, and the critics seem to be content to let him get away with it. Here’s Swofford’s description of his first encounter with the enemy: “Three men were squatting atop the rise and staring at us. We’re within one hundred feet. I could, in two to three seconds, produce fatal injuries to all three of the men. This thought excites me, and I know that whatever is about to occur, we will win. I want to kill one or all of them, and I whisper this to Johnny, but he doesn’t reply. In a draw to our right I see five camels, obviously belonging to these men. The camels are as always, indifferent.” We’ve heard this before: the black humor, the estrangement of the intellectual from his brutish comrades, the defensive perimeter of irony, the starched and capricious commanding officer, and finally the pants-pissing horror of combat itself and the ensuing despair. I’m not belittling Swofford’s experiences in war, nor doubting the truth of his accounts, but I am arguing that his interpretation of his experiences is remarkably lacking in self-reflection and seems to uncritically reiterate—or simply ignore—the disclosures of an earlier generation of war memoirists.

In The Wars We Took to Vietnam: Cultural Conflict and Storytelling, Milton J. Bates identifies five American cultural conflicts that soldier-writers took with them in their rucksacks and on and within which they returned to inscribe their stories. These include: “the war between those who subscribed to different visions of American territorial expansion, the war between black and white Americans, the war between the lower classes and the upper, the war between men and women, and the war between the younger generation and the older.” Because the Vietnam War and the narratives that emerged in its aftermath did not, of course, solve these conflicts, soldier-writers like Swofford and Turnipseed would have carried many of these with them to the desert as well. But they also would have carried the literary legacies of the Vietnam War generation of writers. What’s troubling about Swofford’s book is that he seems not to have read any of them.

In a passage from Jarhead that both Bowden and Kakutani quote, Swofford explains that his motivation for enlisting had to do with his understanding “that manhood had to do with war, and war with manhood, and to no longer be just a son, I needed someday to fight.” And here’s Philip Caputo in A Rumor of War (1977) also explaining his motivation for joining the Marines: “That is what I wanted, to find in a commonplace world a chance to live heroically. Having known nothing but security, comfort, and peace, I hungered for danger, challenges, and violence.” But the remainder of the 400-odd pages of Caputo’s book is, if nothing else, a troubled and troubling reconsideration of that ambition. And almost 20 years after Caputo, and seven years before Swofford, Tobias Wolff had already begun deconstructing this formulation in his memoir, In Pharaoh’s Army: “I’d always known I would wear the uniform. It was essential to my idea of legitimacy. The men I’d respected when I was growing up had all served, and most of the writers I looked up to—Norman Mailer, Irwin Shaw, James Jones, Erich Maria Remarque, and of course, Hemingway, to whom I turned for guidance in all things.” Wolff isn’t finished dismantling his image of the warrior-writer: “I turned into a predator, and one of the things I became predatory about was experience. I fetishized it, collected it, kept strict inventory. Experience was the clapper in the bell, the money in the bank, and of all experiences the most bankable was military service.”

Reading this passage after reading Jarhead makes you instantly understand what it was that so often rubbed you the wrong way in Swofford’s stories: They seem to take place only for his own benefit, even the shameful ones. Again, Wolff provides the disconcerting gloss toward the end of his narrative:

But isn’t there, in the very act of confession, an obscene self-congratulation for the virtue required to see your mistake and own up to it? And isn’t it just like an American boy, to want you to admire his sorrow at tearing other people’s

houses apart. And in the end who gives a damn, who’s listening? What do you owe the listener, and which listener do you owe?

A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, and then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie.

O’Brien goes on to explain the truth of a war story has little to do with literal truth, “because a true war story does not depend upon that kind of truth. Absolute occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and be a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth.” Although Jarhead seduced most critics, it fails this truth test for me, and by the end of it I felt used. Interested readers should pick up Turnipseed’s Baghdad Express instead.

Turnipseed’s experiences in the war don’t seem much different from Swofford’s, despite the fact that he’s a reservist truck driver rather than a sniper, but his reflection on his experience is much more fine-grained. Like Swofford, he relishes his status as book-reading intellectual among the brutes, but unlike Swofford, he’s willing to hold himself up to the ridicule of others and to consider the possibility that those who think he’s pretentious and squirrelly might have a point. Turnipseed’s also willing to grant his fellow marines their humanity, and his account of his gradual acceptance among men quite different from himself manages to say more about them than about him.

And finally, Baghdad Express contains some truly wonderful sardonic cartoons and one ingenious chart from the “United States Marine Corps Philosophy Instruction School,” based on a chart (also in the book) which explains exactly how many inches of bunkers made of various materials will protect against which size bombs. The Philosophy chart takes dead aim at the trope at the center of most memoirs, recovery from childhood trauma or just plain bad luck, and stipulates the number of hours spent alone with the works of various philosophers in order to recover from “child abuse, drunk father, a shitty life, or Ayn Rand.” You’ll want to know that it’ll only take 30 hours of reading Plato’s Republic to erase the effects of child abuse, but you’ll need to devote a whopping 400 hours of your life to Kierkegaard’s Concept of Irony to compensate for your exposure to Ayn Rand.

Turnipseed’s war memoir isn’t perfect either. His bespectacled persona is a little clichéd, as is his characterization of the jive-talking crew of African Americans with whom he shares a tent, but Baghdad Express—more so than Jarhead—pushes the limits of the genre and challenges the now-familiar conventions that have shaped the war memoir since the books about Vietnam began appearing in the 1970s.

Elisabeth H. Piedmont-Marton is a writer who lives in Austin and an assistant professor of English at Southwestern University.