Movie Review

Just Say No To Peeing In a Cup

Larry v. Lockney

Mark Birnbaum and Jim Schermbeck, co-producers and co-directors

Airing Tuesday, July 1

A few weeks ago, while playing tennis at a nearby public high school, I noticed three policewomen escorting quadriped narcs through the student parking lot. The human officers paused occasionally, to examine the car at which a dog was sniffing something illegal. But for the fact that I had arrived by bicycle, my car would have been inspected with the others. But for the fact that I avoid even aspirins, a tennis outing might have served to land me in the wrong court.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees our right to be secure against unreasonable searches and seizures, a right that applies to high school students as much as an adult visitor, even in Texas. Since a search requires probable cause, the presumption of the operation in the parking lot was that everyone who drove to class was guilty. That is a sentiment more worthy of Franz Kafka than James Madison. The San Antonio high school that let loose the dogs of snoop is named for Tom C. Clark, the Supreme Court justice who, after helping supervise the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, eventually achieved renown as a champion of civil liberties.

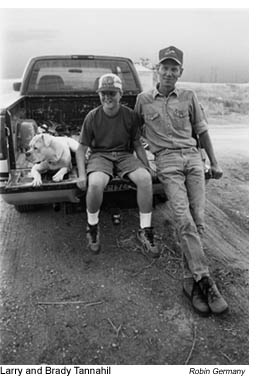

In February 2000, the Lockney Independent School District instituted a mandatory drug testing policy. Periodically, every student at Lockney’s junior and senior high schools would be required to provide a urine sample to determine whether traces of any controlled substance could be detected in their bodies. Lockney, population 2200, is a farming community in West Texas so small and self-contained that a lawyer from Lubbock is resented as a big-city intruder. Jeff Conner came to Lockney to help defend a local father who opposed the drug tests. “It’s like telling my son I don’t trust him,” declares Larry Tannahill, as explanation for why he refused to sign the consent form that would have required his 12-year-old son, Brady, to pee in a cup for school authorities. Tannahill’s resistance led to his son’s suspension and to a legal donnybrook that drew national attention. The dramatic battle is documented in Larry v. Lockney, which will be broadcast by most PBS affiliates on Tuesday, July 1, as part of the sixteenth season of P.O.V., public television’s superb summer series of independent cinema.

“This is the story of Larry, the reluctant civil libertarian,” declares Jim Schermbeck, who, with Mark Birnbaum, directed and produced the film. (Schermbeck is a community organizer who works in Texas with Public Citizen and the National Toxics Campaign, and Birnbaum is a prolific and prized nonfiction filmmaker based in Dallas). “He’s not a rebel,” insists Larry’s wife, Traci. The man at the center of Larry v. Lockney is portrayed as salt of the earth, a cotton farmer whose family has been cultivating the land around Lockney for three generations. “Traci and I have spent 12 years raising our sons, and at a snap of the finger … they’re telling me to take a pen and write down, ‘Son, I don’t trust you,’” Larry explains. “That’s not the way we raised them boys. And I don’t believe they have the right to tell me that’s the way we’re gonna do it.”

Larry is not a Constitutional scholar, merely a concerned parent who saw what he thought was wrong and took action to oppose it. He became a hero of the American Civil Liberties Union, which provided legal and emotional support, flying him to Washington to be lauded as a Fourth Amendment champion and photographed in front of the Declaration of Independence. Not an academic or an intellectual but a kind of Lone Star Jimmy Stewart who simply did what he thought was right, he is the ideal poster boy for an ACLU increasingly stigmatized as unpatriotic during the reign of John Ashcroft at the Department of Justice. “Rights are important because they make a difference in the lives of real people,” explains Ira Glasser, former executive director of the ACLU. “Larry is the kind of guy…that built this country.”

Yet back in the cotton country where he grew up and continues to live, Larry and his family were ostracized within Lockney. He lost his house and his job, and even the family dog was shot at with a paint gun. “He did a lot of damage to the community,” says an unidentified voice from Lockney. “It’s worth your job,” concludes Larry. “It’s worth some ridicule from your community if you believe in what you’re fighting for.”

Birnbaum and Schermbeck situate the story within the particular context of flat West Texas cotton land. They bring their cameras to Friday night football and the Floyd County Pumpkin Festival. They record the opinions of the school board members, local farmers with no expertise in law but dedicated to fulfilling their responsibilities as stewards of education within the district. It is after hearing complaints from faculty and administrators about increased incidents of drug abuse that the board decides to institute mandatory testing. Lisa Mosley, an art teacher at Lockney High, tells of students who came to class stoned or soused and poisoned the environment for learning. Donald Henslee, an attorney for Lockney, explains that public schools are expected to serve in loco parentis and that it is necessary to sacrifice some individual rights for the greater collective good. “When you go into an airport, don’t you have a reduced expectation of privacy?” he asks. “Everyone’s decided that it’s worth the safety issues to go through the pat-downs and other inconveniences.” Do the laudable ends of creating drug-free zones justify the shabby means of running schools like airports? Will it fly in federal court?

The most theatrical moment in Larry v. Lockney occurs in July 2000, when Larry Tannahill is granted an appeal before the school board. Virtually the entire population, many wearing T-shirts advocating drug tests, shows up for the hearing, which is held in the Lockney High School gym. “It was pretty close to a circus,” recalls attorney Conner, who must have felt like a performer in a freak show, as he squeaked across the silent gym to face the hostile crowd. A local reporter is threatened with physical harm. Standing up with Larry against the entire community, Conner invokes the Bill of Rights to defend the presumption of innocence. But the occasion is like a Lockney High School pep rally, and the two lonely opponents of preemptive testing are the enemy team. Neither the board nor the audience has come to the gym in order to be convinced. The board votes unanimously to confirm its policy of requiring urine samples from all students, and the case makes its way, slowly, through the courts.

In March 2001, U.S. District Judge Sam Cummings rules that the Lockney policy of mandatory drug testing violates the Constitution. With limits on its budget and its legal insurance, the Lockney Independent School District determines that it simply cannot afford to pursue a further appeal. It agrees to pay some of Larry’s legal fees and to return to a policy of testing only students who appear to be under the influence, volunteer for testing, or wish to participate in extracurricular activities. One board member is puzzled by the outcome of the conflict. “It helped the school,” he says about the discredited policy of drug testing. “It helped those students.” Lisa Mosley is bitter. “I don’t think I want to teach much longer,” she complains. “It’s the small minority who get their way.” Opposing mandatory drug tests, Larry Tannahill is a very small minority of the Lockney population, but the Bill of Rights was designed precisely to protect the minority against tyranny by the majority.

“It wasn’t just a fight for my two boys,” says Larry, an unlikely litigant. “It was a fight for the nation’s children. The Constitution won.” Of course the war is not over, any more than the war against wars has been resolved. One has to wonder how welcome the Tannahills are in Lockney now. One has to wonder also about our tendency to declare war against various blights—drugs, terrorism, poverty, cancer. Too often invocation of the word “war” is used to stifle discussion and to redefine dissidents as traitors. Drug abuse is indeed a scourge, but collective hysteria is one of its most malignant symptoms. Schools have an obligation to inform their students about the hazards of controlled substances but a primary responsibility to teach respect for Constitutional principles. The case of Larry v. Lockney is an extracurricular lesson in the value of brave dissenters like Larry Tannahill, the Lockney farmer who was willing to resist the lures of lockstep thinking.

Steven G. Kellman teaches comparative literature at the University at Texas at San Antonio and is the editor of Switching Languages: Translingual Writers Reflect on Their Craft.