Movie Review

God's Little Favela

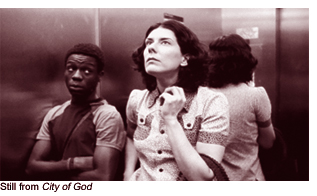

City of God

City of God opens with a series of cuts: a knife chops carrots and slices a lime, a hand plays a slashing samba rhythm on a little guitar. The rhythm of the knife on the cutting board and the guitar churn forward, and the camera cuts from close-up to close-up. Footsteps on pavement, more music, then a gang of young kids, eight, ten years old, chasing a runaway chicken through the streets of a Brazilian slum with pistols drawn. It’s funny, it’s exciting, it’s stylish–and it’s also profoundly unsettling.

The film is named for the Cidade de Deus (City of God), a hardscrabble suburb of Rio de Janeiro that was founded in the 1960s as a housing development designed to keep poor people away from the center of Rio. Since then it’s grown into sprawling favela, or slum, with over 120,000 residents. The film is based on the best-selling novel by Paulo Lins, which in turn is based on Lins’ life. Our narrator, nicknamed Rocket, is a composite of Lins and one of his childhood friends. Rocket traces the story of a group of his playmates—with names like Li’l Ze, and Carrot-Top—who grow up to be ruthless bandits and the de facto rulers of City of God. They go to funk dances, hang out with Pentecostal Christians and Afro-Brazilian religious men, swim at the beach, and hide from crooked cops. They also murder, maim, rape, and pillage their way to the top of the heap, becoming—for a moment— the most infamous criminals in Rio. Rocket, in turn, becomes the gang’s semi-official photographer.

The film is by turns exhilarating, terrifying, funny, confusing, and depressing. When “war” breaks out (over drug profits, some imagined slight, or sheer sociopathy) the gunshots rip through neighborhood houses, blowing family portraits off walls and shattering the cheap trinkets perched on shelves and end tables. One particularly gruesome shoot-out leaves dead bodies draped pathetically across the street, falling off sidewalks and down stairs. The God in the title could be the bastard son of Mammon and Ares.

The film is co-directed by Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund. Mierelles is a Clio award-winning commercial director who has also made kids’ shows for Brazilian TV. He enlisted Lund because she’d had experience working in the favelas, shooting Brazilian rap music videos and making a documentary on real-life drug wars. They wanted to work with children from City of God and other favelas, so they set up acting classes and workshops for kids from the area. The classes served as both clandestine auditions and long-form rehearsals. Only two of the film’s stars were professional performers—an actor and a samba singer. The rest were chosen from the 200 kids the filmmakers worked with in their classes.

In one truly haunting scene, a little kid has been caught shoplifting in a neighborhood under Li’l Ze’s protection. The child has to pick his punishment: Does he want to be shot in the hand or the foot? Most of the intimate, emotional moments in the film are seen from afar in wide shots, presumably because the amateur cast couldn’t sell the scenes in close-up. This time the camera stays right in the little boy’s face as he breaks down in anguish and terror. The film’s shaky, hand-held camera and washed out colors—it was shot on film, transferred to video, and then back to film to make it look grittier—make the moment feel all too real. I cringe whenever I try to imagine what the filmmakers did to that little boy to get that performance, or what kind of experiences he was drawing on from his own unimaginable life.

In Brazil the film has been one of the biggest domestic hits ever, partly because in the past two years the blood has been spilling off the silver screen and out of the slums, down into chic shopping districts and the corridors of power. According to a recent Ford Foundation- sponsored study by the Brazilian NGOs Viva Rio and the Institute for Religious Studies, 3,937 youths died from firearm-related injuries in Rio from 1987-2001. That puts Rio on pace per capita with the Palestinian Occupied Territories, where 467 Israeli and Palestinian youths were killed during the same period, which coincides with the first and latest intifadas.

Most of these kids aren’t in a war in any technical sense. They’re just involved in an extremely dangerous but quite lucrative business. According to Robert Neuwith, writing in the September/October 2002 issue of NACLA’s Report on the Americas, something in the neighborhood of $15 million worth of marijuana and cocaine pass through the slums of Rio de Janeiro every month. The drug gangs who control the trade employ lots of youngsters to work as runners and lookouts and killers.

As we see in City of God, the gangsters aren’t a force of pure evil. They provide residents with security from theft and violence (except when they get caught in the crossfire between police and the gangs, or between rival gangs). The gangs provide protection for local businesses, build facilities like soccer fields, sponsor dances and other social events, and connect with the community in ways that the legitimate government has never done. Drug dealing provides jobs and capital, and is a part of the social fabric of communities like City of God, for better and for worse.

Brazilians often talk about “capitalismo selvagem,” which means savage capitalism. It’s the same capitalism we have here, but they often have a closer view of the action. The differences between rich and poor, between workers and owners are stark; the power that maintains these divisions is often brutally obvious. When I lived in Brazil a decade ago, I saw a man who was in the final stages of starving to death lying on the sidewalk. He was in front of a bakery and across the street from a McDonalds. In the chic neighborhoods of Rio, off-duty cops have been known to free-lance for death squads that remove inconvenient homeless kids from the streets. The slums of City of God are a quick five-minute car ride from the gated luxury condominiums of Barra de Tijuca.

More recently, elite Rio has increasingly found itself under the gun from thugs who work for Freddie Sea-Shore and other real-life, colorfully-nicknamed drug gang leaders. Last October and again in December, the gangs used intimidation to close businesses throughout the city for a day (including tony boutiques in Ipanema and Copacabana), apparently to protest the removal of cell-phone privileges from gang leaders in prison. They have also taken to halting traffic on the city’s freeways to do wholesale robberies and carjackings, as well as occasionally throwing bombs and shooting machine guns at places like city hall and the governor’s mansion. In the days leading up to Carnaval in February, the gangs fire-bombed buses and threatened shopkeepers again. For the first time ever—including during the military regime in the 60s and 70s—the army patrolled the streets of Rio during Carnaval.

One of the reasons the left-leaning Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva was elected president of Brazil last year was that it was hoped he would be able to forge a union between Brazil’s profoundly divided rich and poor. The violence and desperation so heartbreakingly observed in City of God can only take root in that gap.

Early in the film one of the young hoodlums says, “To be a bandit you need more than just a gun in your hand. You need an idea.” The filmmakers are paraphrasing the motto of Brazil’s gritty Cinema Novo movement: A camera in the hand and an idea in the head. With this film, they’re also exhorting us all—artists, politicians and citizens of the world—to envision and incarnate another world, one where kids don’t kill one another for a few dollars and a fistful of respect.

Jake Miller writes about culture, history, and science. He lived in Brazil in the early 1990s.