Out of Service

Inside Texas' nightmarish mental health system

The Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation recently revealed that, after years of massive under-funding from the Texas Legislature, the cash-poor agency can serve only a third of its “priority population.” This means of the 550,000 Texans with severe mental illness, the state offers care to about 150,000. Put another way, 400,000 people with crippling conditions such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, and paranoid schizophrenia have been left to fend for themselves. Shocking numbers like these illustrate why advocates for the mentally ill have been shouting from rooftops this legislative session about the crisis in Texas’ mental health system. But, still, they’re just statistics, drowned amid the torrent of social service horror stories flooding the legislature these days.

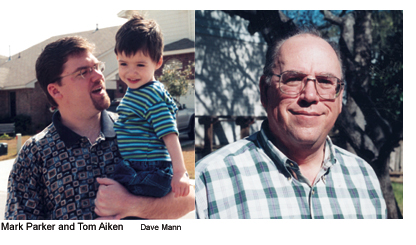

When you move past the numbers and meet some of the half million mentally ill people, and their families, whom the state has abandoned, you realize “crisis” is much too timid a description. The term simply doesn’t convey the entrapping Catch-22s facing families of the mentally ill—no-win scenarios that could ensnare almost anyone, regardless of where they live or how much they earn. These victims include: a comfortably middle-class executive at Dell who’s forced to give up his daughter solely to access basic mental-health treatment unavailable anywhere else; a machinist, who, after pleading with the state for years to hospitalize his schizophrenic daughter, comes home to find she has murdered his wife; a mental health advocate, who watches her untreated son tumble through three state agencies and into the criminal justice system.

State funding for mental health services, adjusted for inflation, has declined 6 percent the past 20 years, while the state’s population, and the need for mental health care, sky-rocketed. The legislature hasn’t increased funding for children’s mental health in nearly 10 years. The hundreds of thousands who go untreated don’t disappear; their illnesses aren’t magically cured. Instead, many are flung into the criminal justice or child welfare systems. The Texas prison system now serves as a de facto mental health agency, costing the state three or four times more money than if it paid for preventive treatment. With the state facing a $10 billion budget gap, the crisis, if that’s what you want to call it, is about to get much worse.

Parker sits in the second-to-last row, listening to the three hearings ahead of his. The testimony is sad, but standard for neglect and abuse cases: drug-addicted parents, an alcoholic and abusive mother, angry in-laws and grandparents. Parker has come straight from his office at Dell Computers in the Austin suburb of Round Rock. In three years at Dell, he’s worked his way up from technician to supervisor to manager. At 33, Parker looks like any average businessman you might see smoking outside an office building. He’s roughly six feet, with a broad build and the makings of a cozy gut beneath his shirt and tie. His blond hair is neatly parted, goatee precisely trimmed.

Unlike the cases unfolding before him, Parker volunteered for a negligent parent tag and relinquished custody of Lacey to the Texas Department of Protective and Regulatory Services (PRS), which placed her in a treatment facility. He did that for one simple reason: It was the only way Lacey could get much-needed treatment for her mental illness. Although Lacey gets care, turning his daughter into a ward of the state is not only an emotionally wrenching decision for Parker, it also means a neglectful parent label will follow him for a long time. He says he doesn’t care. With such a dearth of mental health services available in this state, Parker had no choice.

A growing number of parents are making the same painful decision. According to PRS, nearly 300 parents in 2002 alone relinquished custody of their children solely to access mental health services they couldn’t get anywhere else. Housing each one of those children costs the state $110 a day, according to PRS. The agency has no data before last year so there’s no way to know how many families have gone through this, but mental health advocates put the number in the thousands. PRS refers to this ironically, and tellingly, as Refusal to Accept Parental Responsibility.

In November 1999, PRS removed 8-year-old Lacey from her mother’s custody and gave her to Parker. According to Parker and PRS officials, Lacey had been ignored and neglected since she was a year old and had been abused by several of her mother’s boyfriends. Lacey’s therapist and psychiatrist theorize the neglect at a young age, coupled with abuse and a history of mental illness in her mother’s family, has caused a nasty mingling of severe depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and reactive attachment disorder. These conditions cause intense feelings of jealousy and lead Lacey to act out in alarming ways.

After moving in with Parker, Lacey’s problems began to manifest in minor incidents: attacking kids in school or in the neighborhood, and sneaking from her room at night to gorge herself on candy. In fall 2001, her condition deteriorated. Lacey began saying she wanted to kill herself, and her acting out, including sexual aggression, became more severe.

Lacey spent most of November 2001 in Cedar Crest residential treatment center in Belton—the first of several inpatient stints. But after four weeks, Parker’s insurance company pressured hospital officials to release her. Parents of mentally ill children are constantly in a tug-of-war with insurance companies over residential treatment. Most plans cap the number of residential treatment days and won’t cover more than a few weeks at a time because, as Parker put it, “With mental health, you don’t really see many results and it’s very costly.” Parker was comparatively lucky. His Dell benefits package offered a Cadillac health insurance plan, which covered Lacey for more than the standard few days.

In February 2002, Lacey began lashing out again, attacking other children at school, and her half-siblings Joshua and Aileen. The Parkers sent her back to Cedar Crest for another four-week stint, until the insurance company had had enough. So Cedar Crest referred Lacey to outpatient care at Shoal Creek clinic in Austin. After just a week, Shoal Creek admitted her to its residential treatment facility. After she stabilized, Lacey was released in mid-March 2002 and returned to school to finish fifth grade. The Parkers’ made arrangements with school officials for Lacey’s special care. While she remained in regular classes, her curriculum was adjusted for her attention deficit disorder. School officials never left Lacey unsupervised with other children and always accompanied her to the bathroom, where she had often sexually acted out before. At the same time, she was seeing her therapist regularly and, at times, taking five medications, much of it covered by insurance. The setup worked well, and Lacey finished the school year without incident.

The first week of last July, Parker traveled to India on business. One night while Parker was away, Lacey attacked and sexually molested Aileen. Miriam rushed Lacey back to Shoal Creek. The insurance company, though, refused to pay for more residential treatment, and Shoal Creek was about to release Lacey again. But her psychiatrist strongly warned against it, and Lacey was transferred to Meridell Achievement Center. The ranch-style facility north of Austin has an excellent reputation. Officials there ignored insurance company urging to release Lacey. As a result, she spent six months in residential treatment at Meridell and seemed to stabilize enough for a return home.

But a few days before her scheduled release, 11-year-old Lacey was caught in bed having sex with another girl. Lacey’s therapist believes, according to Parker, that since she’s rarely experienced a supportive family environment, Lacey views residential treatment as an escape and does anything she can to remain there.

By last fall, Parker was running out of options. Parker’s high-end insurance plan had finally run its course. The company flatly refused to pay for more residential treatment, saying Lacey’s care was a long-term issue and wasn’t its responsibility. “Can you imagine an insurance company saying that to a kid with cancer?” Parker said. “Whenever they want to they can decide they’re not going to cover something anymore.”

Mental illness can be just as serious and chronic as cancer, but insurance companies, in most instances, are not obligated to cover the medical costs. Rep. David Farabee (D-Wichita Falls) and Sen. Leticia Van de Putte (D-San Antonio) have filed children’s mental health insurance parity bills in the legislature that would require insurance companies to treat chronic mental illness the same as chronic physical ailments. The measure could solve the problems of people like Parker, who don’t qualify for Medicaid, but whose insurance coverage has been capped. A similar bill nearly passed last session but was scuttled in Senate committee. It was a tough defeat for Farabee, a long-time mental health advocate (the mental health center in Wichita Falls is named after his mother, a former volunteer).

By November 2002, it was clear Lacey would have to leave Meridell soon. Her psychiatrist and therapist advised against a return home. Desperate to find care for Lacey, Parker started cold calling residential treatment centers. Parker found a few facilities that privately contract with the state. But administrators at those facilities told him only PRS could place kids in their centers. “We called and tried to have them help us get placement,” Parker said. “They said because Lacey was not a victim, or current victim, she was not eligible for their help.” PRS officials told Parker Lacey would be eligible only if he admitted negligence. PRS could then take custody and get her treatment. Parker refused to surrender custody at first, hoping to find other alternatives.

He soon discovered what many other Texans already have—there are no other alternatives. MHMR offers little. The Waco Center for Youth, the lone statewide hospital for children, has a six-month waiting list to get one of its 81 beds. The other regional state hospitals are 98 percent full and nearly impossible to get into. Lacey’s condition was too severe to subsist on outpatient treatment from an MHMR community center. But even then, she’d likely have to wait months just to see a therapist. Private church organizations said Lacey was too severe a case for them. Other privately run residential facilities would take her, but without insurance, Parker would have to foot the $400-per-day cost, which he could never afford. He even fruitlessly tried out-of-state facilities. Parker makes too much money to qualify for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. So once his insurance ran out, he was stuck.

Eventually he came back to PRS, and pleaded with the agency to grant Lacey admission to a facility. PRS informed him the agency had identified Lacey as a sexual predator, and if she returned home, the agency would remove Parker’s two younger children. The PRS system, designed to protect abused children, clearly isn’t built to fill the mental health provider role its been wedged into. Moreover, some in the agency don’t fully comprehend that PRS is increasingly getting into the mental health services business. Some PRS officials seem to believe any parent who would relinquish a child is truly neglectful, and they try their best to discourage it, hence the title they bestow, Refusal to Accept Parental Responsibility.

Parker says two PRS workers flatly told him to stop neglecting his parental duty and care for his child. “That’s exactly what we were asking them to help us do,” he said. “If we let Lacey come home, they would take our two little ones away. You’re making me choose between my two little ones and her.” Faced with this hideous dilemma, the Parkers decided they had only one choice: turn Lacey over to the state.

So on Dec. 20, the Parkers refused to pick Lacey up from Meridell. PRS was contacted, and the agency sent her to an emergency placement shelter, where, a few days later, the Parkers visited to celebrate Christmas. At a hearing in early January, Judge Jergins officially entered a court order of negligence against Mark Parker.

The purpose of today’s hearing is simply to update the judge on Lacey’s condition. At this point, little will be decided. Cecelia Turrin, Parker’s PRS caseworker, recommends Lacey be placed in a residential treatment facility as soon as possible. Hopefully, the agency can find an opening near Austin. It’s not unusual for PRS to place relinquished children several hours from their families. Under PRS rules, families who relinquish custody have a yearlong probation period before they surrender all parental rights. Parker hopes Lacey will stabilize enough by next Dec. 20 to return home. If not, she becomes a permanent ward of the state. In the meantime, Parker pays $500 a month child support to PRS. Lacey’s mother still owes years of back child support to Parker, though the state attorney general has yet to track her down.

By the day of the hearing, Lacey has stayed in the temporary placement shelter nearly five weeks awaiting transfer. The Parkers are allowed two visits a month. While living in the shelter, Lacey has temporarily returned to school, and Turrin asks that Lacey transfer to residential treatment after Feb. 14 so she can attend a school Valentine’s Day dance she’s looking forward to. The Judge agrees. Parker is lucky he’s been assigned Judge Jergins. Mental health advocates say other less astute judges often badger parents in hearings, trying to convince them to take their children back. Jergins clearly understands the subtleties of Parker’s case. Within a week, Lacey will be moved to a residential treatment facility in Austin, where, several weeks later, she will celebrate her 12th birthday. Judge Jergins sets another status hearing for early June, looks at Parker sympathetically and says “Good luck.”

In this position, she sees first hand Texas’ neglect for the mentally ill. She puts it bluntly, ” end up in jail because we’re cutting funding . Is that fair to kids?” Instead of offering adequate treatment, she says, Texas simply sweeps the mentally ill into the criminal justice, juvenile justice or child welfare systems. Sometimes all three, as happened to her son Daniel.

Texas ranks 46th in per capita mental health spending. Hence, two-thirds of the most severely ill go without services. As MHMR services become more scarce, more money floods the criminal justice system to pick up the slack. Perhaps the most telling figure about Texas’ mental health system is this: MHMR state hospitals offer roughly 2,400 beds for inpatient care of the mentally ill. Texas prisons offer 2,800 beds for the same services.

Like many mental health advocates, Garza became involved in the field after trying to find treatment for a family member with mental illness. Her son, Daniel, now 17, suffers from depression and ADHD. His problems began at a young age (he once slugged his first-grade teacher). He had his first psychotic break in the third grade when Garza’s youngest son was paralyzed. Since then, Daniel has had two dozen hospitalizations and seven stays in residentia

treatment, mostly in the juvenile j

stice and child welfare systems. But, Garza believes, Daniel could have become a productive member of society had he been treated effectively early on. Mentally ill children who receive treatment at a young age often become success stories, the ones who graduate high school and college and find solid careers.

For Daniel, though, the state offered little. The MHMR community center provided 30-minute counseling sessions every four to six months, and medication was spotty at best. Garza could rarely squeeze him into an MHMR state hospital, and when she did, the stays were too short. Her insurance covered some residential treatment, but that soon ran out. “I spent two years sleeping in the hallways so my son couldn’t get to his brother’s room and do any damage,” she says. In July 2000, after what Garza describes as the best two years of Daniel’s life, he snapped and viciously beat her. He was arrested and tossed in the juvenile justice system. After Daniel’s release, juvenile justice officials wanted Garza to take Daniel home again. She refused, saying she couldn’t care for him alone. At that point, without any more insurance coverage, Garza was forced to relinquish custody to PRS. He was charged in the adult criminal justice system for the first time last November, and lives in an Austin shelter awaiting trial. Garza says Daniel will likely be institutionalized the rest of his life. “How much is that going to cost the state?” she asks rhetorically.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice estimates the state pays an average of $30,000 annually to incarcerate one mentally ill inmate. An estimated 150,000 inmates and parolees in Texas have serious mental illnesses, as do nearly half the children in the juvenile justice system. The problem is reaching epidemic proportions. In the past seven years, the percentage of juvenile offenders with severe mental illness has risen 23 percent, according to the Texas Youth Commission. When it comes to treating the mentally ill, Texas acts much like a teenager compiling credit card debt—instead of funding services up front, the state postpones its problems and pays three or four times more in the end.

The solution to this cycle, mental health advocates say, is a form of treatment called wraparound. In this model, children receive community-based services at a young age. Ideally, state and local agencies work with therapists, school administrators, religious groups, and just about anyone to treat children at home, with occasional hospitalization if necessary. It’s a proven approach other states have used to transform their care for the mentally ill. Texas can too. The state and federal government have funded pilot wraparound programs in Texas, mostly in urban areas. The fledgling programs take years, and substantial initial funding, to get off the ground (coordinating multiple agencies on multiple levels of government is tricky). If Texas invests the time and money, wraparound will save lives and huge sums of state funds in the near future, believes Garza. “The question is, where do we want kids to be,” she says. “In the military, college graduates, paying taxes, or in Wackenhut ?”

The proposal is appalling. MHMR will carve nearly $300 million from its already flimsy appropriations. To accomplish this, the agency will slash $53 million in funding for its 42 MHMR outpatient community centers around the state, depriving more than 10,000 people of mental health services. That cut will cost the agency another $60 million in federal matching funds. Hale also proposes closing one of the 10 inpatient state hospitals (this idea proves so unworkable that the agency later decides to keep all 10 state hospitals open, but to privatize two of them). In addition, Hale says MHMR will cut funding for indigent care in its Dallas-area NorthSTAR program, swiping services from another 12,000 of the poorest mentally ill. For an agency already serving less than a third of its so-called “priority population,” this budget appears disastrous. Worse yet, the budget reductions also axe many of the pilot wraparound programs, not only deepening the crisis but extinguishing the very programs that offer solutions.

The budget cuts will be hardest felt in rural areas like the flat farmland of West Texas’ Concho Valley. Michael Campbell runs the small MHMR community center in San Angelo. The center is the lone mental health clinic for the surrounding seven counties. This being West Texas, only 130,000 people live in those seven counties, but some must drive up to 85 miles to reach the San Angelo clinic.

The center is so poorly funded, Campbell and his staff struggle just to provide what services they can. For adults, MHMR funds the center $1.2 million. With that, along with Medicaid, Campbell and his staff treat more than 500 adults each month. Still, they must turn away six of every 10 adults seeking treatment, simply due to cash shortages.

Campbell estimates 1,400 children in his area require mental health services. MHMR provides enough money to care for 65. Patching together a mix of Medicaid, CHIP and funds from a pilot wraparound program called Texas Council on Offenders with Mental Impairments (TCOMI), the clinic scrounges up services for about 300 children a year. That’s not even a quarter of those who need it.

Think of mental health funding as a three-legged stool, comprised of MHMR, Medicaid (and CHIP), and the criminal justice system. The legislature is weighing 12 percent cuts to all three legs. Those cuts, Campbell says, would mean his clinic couldn’t treat any of those 500 adults each month. The center could offer “emergency services” only. Care for children would be substantially reduced as well. “It would be balancing the budget on the backs of children,” Campbell says. “You hear that a lot and it’s a cliché, but it’s true.”

Linda Aiken was diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic eight years ago, at age 21, and was forced to leave her job at a nursing center. She struggled with the disease for years. At one point, she improved enough, thanks to a new generation drugs, to work for two years at Wal-Mart. But in 2000, the drugs’ effectiveness began to wear off, and Linda’s condition started a steady descent. By November 2001, her delusions became so intense that Tom and his wife Kathy would drive their daughter around Hill Country back roads all night to calm her down.

Tom Aiken tried for two years to secure adequate services for Linda, both from MHMR and private doctors. But drugs had little effect and counseling sessions weren’t much help, either. Linda needed to be hospitalized. But all state hospitals, then as now, were full. Even if there was room, it’s unlikely Linda would have gone voluntarily, and state officials told Tom Aiken they couldn’t commit Linda until she demonstrated she was a threat to herself or others. Tom argued that, as a delusional schizophrenic, Linda would never make such an admission until it was too late.

By early 2002, Linda’s delusional spats were worsening. One morning, Linda walked into the kitchen and announced she had been pregnant the night before, but wasn’t this morning. She demanded to know what Kathy and Tom had done with her baby. It was clear Linda needed 24-hour supervision. So Kathy left her job to stay home and care for her daughter. By the July 4th weekend of last year, Linda’s condition was the worst Tom had ever seen it. He was still desperately trying to get Linda hospitalized, but he couldn’t get her into an MHMR state hospital. Private facilities cost $1,200 a day. Tom calculated it would take Linda at least a month to stabilize and he couldn’t afford $40,000.

Sunday, July 7, was Tom and Kathy’s 29th wedding anniversary. The next day, Tom went to work. Kathy called to say everything was fine that morning. Don’t forget to get orange juice on the way home, she told him. Shortly after that phone call, Linda Aiken attacked her mother. Linda weighs 340 pounds. She laid on top of her mother until Kathy suffocated to death.

After the murder, Linda was finally put in residential treatment, at the North Texas State Hospital, the center for defendants found incompetent to stand trial. Aiken flatly blames Kathy’s death on the state’s lack of mental health services and state officials’ inability to commit Linda. Because of its mental health crisis, he says, Texas is riding the cusp of a wave of similar preventable deaths. “People ask me all the time, how did Linda fall through the cracks?” Tom says. “I tell them, there was no floor. Do I blame the State of Texas? You better believe it. I’ve looked back over it and wondered if there’s anything I could’ve done. And if I knew then, what I know now, I’d have moved to Kansas.”

A few days after Aiken’s testimony, I intercept Arlene Wohlgemuth after a press conference. As chair of the appropriations subcommittee on health and human services, she has a large say on funding for mental health services. Wohlgemuth—a staunch conservative and anchor of the no taxes, cut spending crowd—seemed genuinely moved by the mental health testimony, especially Tom Aiken’s story. “It’s heart-breaking,” she says when I mention Aiken. But when I ask about increased funding for mental health, she offers typical politicians’ assurances. “I’m looking under every rock to find more funding,” she insists. She makes clear, that for now, that doesn’t include increased taxes.

How many more deaths, ruined lives and shattered families are necessary before Wohlgemuth and her colleagues change their minds?