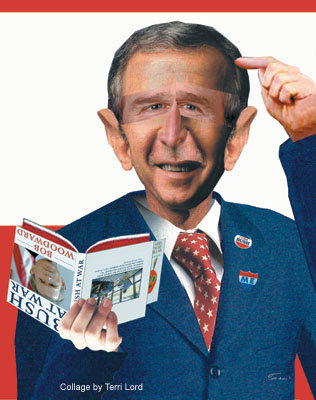

Comandante W.

Grading Shrub's First War

I don’t know how much of an advance Simon & Schuster gave Bob Woodward. I do know they used to give him $1 million per book, up front. They should have given him about fifty bucks for this one, if it’s judged for style or thoughtfulness. It’s a cluttered, go-nowhere, pretentious piece of “pseudo-investigative” journalism.

And yet I’ll have to admit it’s useful. That joke of a commission, which Henry Kissinger was supposed to head (and quit, rather than disclose the identities of his business cronies) to uncover the reasons it was so easy for terrorists to hit the New York towers and the Pentagon, can disband right now.

Some of the answers are right here in Bush at War. The CIA in particular and the Bush administration in general simply screwed up, royally.

Meet George J. Tenet, director of the CIA and other parts of the vast U.S. intelligence community. He has a keen brown nose (he led the effort to rename the CIA headquarters for the elder Bush) but is very cautious when it comes to sniffing out terrorists.

“Tenet himself had been too fearful and hesitant prior to September 11, too afraid to push the envelope,” writes Woodward, always quick with the cliché, although he says that as early as 1998 Tenet had declared “war” on Osama bin Laden.

Some war. Tenet had asked President Clinton for money to let him reestablish a covert operation in Afghanistan, and Clinton had given it to him. “But he had not come out straight to Clinton or Bush and proposed, ‘Let’s kill him’.” Tenet had neither asked much of Bush, nor told him much, which would explain why Bush, according to Woodward, “did not pursue the bin Laden threat aggressively enough” before September 11.

Apparently the last coaching on terrorism he got from Tenet was the week before he was sworn in as president. Tenet had briefed him–and briefed is the right word–on the three most pressing threats. Maybe Bush can be excused for not paying much attention because in addition to bin Laden and weapons of mass destruction, Tenet had listed as the third major threat–hang on to your hat–”the rise of Chinese power, military and other.”

If Tenet presented bin Laden as no more of a threat than our valued trading partner China, no wonder Bush didn’t get excited. I believe the president when he tells Woodward that “I knew bin Laden was a menace . . . knew he was a problem . . . knew he was responsible for the previous bombings. I was prepared to look at a plan that would bring him to justice, and would have given the order to do that.”

But the CIA didn’t give him a plan, so “I didn’t feel that sense of urgency.”

As for Tenet’s claim that he had not been provided “lethal authority,” he means that neither president anointed him with legal permission to kill bin Laden. Several times in this book, Woodward quotes people around Bush–particularly the CIA–as saying they would have gone into Afghanistan and killed the rogue if a federal law hadn’t prohibited such assassinations. That was just one of the CIA’s typically bogus excuses for not taking action. The federal law against assassinations overseas was written only to protect rulers, for the obvious reason that our presidents haven’t wanted to do something that might incite revenge that would endanger their own necks.

The law does not protect free-wheeling killers. After bin Laden’s outfit bombed U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, Clinton ordered the military to launch 66 cruise missiles into terrorist training camps in Afghanistan, hoping to kill bin Laden. The aim may have been bad, but the action was perfectly legal.

Excuses, excuses. The CIA always had plenty to explain its inaction. It said it had wanted to send in an elite military squad to attack bin Laden’s hideout but had held off because “intelligence reports showed that bin Laden had his key lieutenants keep their families with the entourage, and Clinton was opposed to any operation that might kill women and children.” Oh yeah? What about his missile attack?

Anyway, that yarn about Clinton’s sensitivity doesn’t explain why the CIA didn’t repeat its request for the elite military squad attack when Bush got in the White House. As he would prove during the Afghanistan engagement, he certainly had no qualms about collateral damage. (And if there was any doubt about it, Tenet could have gotten permission from Bush. Recently the President has done exactly that: prepare a list of terrorist leaders the CIA is authorized to kill.)

Ever since 1998, the CIA had been sending secret paramilitary teams into Afghanistan to bribe tribal leaders and the Northern Alliance for information. They paid millions of dollars for it. It’s hard to believe that all of that bribery didn’t produce the location of bin Laden, or at least the general area where the hunting would be best. And if it didn’t, why did they keep paying the bribes?

Four days after the terrorist planes hit New York and Washington, Tenet met with Bush at Camp David. He came carrying a briefcase stuffed with TOP SECRET (Woodward always likes to capitalize those words) documents and plans covering more than four years of work on bin Laden, al Qaeda, and worldwide terrorism.

Tenet told Bush that his material showed the attacks on this country were “the result of two years’ planning. Several of the reports specifically identified Capitol Hill and the White House as targets on September 11 . . . It was consistent with intelligence reporting all summer showing that bin Laden had been planning ‘spectacular attacks against U.S. targets’.”

It was the first time Tenet had given Bush this stuff.

Now, if you had been the President and your CIA director brought you all that material the attack, how would you have reacted? You would have thrown the spook out on his ear, right? You would have fired him on the spot, right?

Not Bush. Incompetence, including his own, doesn’t seem to bother him. Three weeks after the terrorist attack, Bush’s civilian warlords met and talked and talked, and then realized: “None of them really had any idea, neither conventional nor unconventional. They were underprepared for what had happened on September 11, and uncertain about the path ahead.”

Consider our great military leaders. We are giving the Pentagon nearly $400 billion a year, and what do we get in return? “The military, which seemed to have contingency plans for the most inconceivable scenarios, had no plans for Afghanistan, the sanctuary of bin Laden and his network,” Woodward writes. “There was nothing on the shelf that could be pulled down to provide at least an outline.”

General Henry B. Shelton, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, went to Camp David to give our civilian warlords what the Pentagon considered the best options for hitting Afghanistan. One target he offered was the al Qaeda training camps. Unfortunately, there was one little problem: As everyone in the room knew, the camps were empty.

Unless my memory has failed me, Bush assured us that our military forces were going into Afghanistan to capture or kill bin Laden. “Dead or alive.” Wasn’t that his catchy phrase? He must have thought bin Laden would play fair by sticking around until we started shooting at him. Yeah, well, I guess he got tired of waiting. Three weeks after September 11, we still had not a solitary soldier in Afghanistan.

A month after September 11, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was still talking about “locking things down so that” bin Laden and his gang “do not leave. We want to keep people bottled up.”

Incredible! There were numerous passes across the mountains, and we still had nobody there to prevent the escape. In response to Rumsfeld, Secretary of State Colin Powell, a man of infinite tolerance for his dim-witted colleagues, noted “almost with a sneer” (Woodward’s description): “Bottled up? They can get out in a Land Rover.”

Or consider Bush’s national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice (about whom Woodward reaches for something positive to say, and comes up with the information that she has “a near perfect posture, a graceful walk and a beaming smile”).

I draw your attention to the last word in that title, “adviser.” Woodward tells us that “It was her style not to commit herself unless the president pressed.”

But maybe it was just as well she didn’t offer much advice. One of the few suggestions we hear from her is that perhaps it would be a good public relations gimmick–Woodward calls it “an insurance policy”–to start a little war on the side, to distract critics in case the Afghanistan war went sour.

That crowd, especially Pentagon boss Donald Rumsfeld, didn’t think there was anything screwy about her suggestion. Rumsfeld, in fact, was telling his cohorts almost from the first days they met in a war conference that they should go after Iraq, right then, without delay, before they got much deeper involved in Afghanistan. And Cheney liked the idea, too, very much. He “was beyond hellbent for action against Saddam. It was as if nothing else existed.” But like a good little vice president, he was up and down on the idea during this period, paying close attention to Bush’s barometric comments on the best timing for the proposed Iraq adventure.

You’ll get a kick out of our head-tilting vice president. Actually, you won’t hear much from him worth remembering until the White House gets some serious warnings that the terrorists might be coming its way. At that point, without asking permission from his president, Cheney declares that he’s out of there, fast. Not that he was frightened, oh no. Not brave little Cheney. He was heading for the hills (literally), he explained, “to preserve the government, its continuity of leadership.”

Woodward says Cheney “had been training all his life for such a war. His credentials were impeccable . . .”.

Impeccable? Well, he had been chief of staff to one of our most forgettable presidents (Ford), congressman from one of our most insignificant states (Wyoming), and the elder Bush’s secretary of defense during our first war with Iraq, which the present arms buildup indicates we must have lost. That’s “impeccable” to Woodward.

We get an equally fawning profile of our pious president, who tells Woodward that war “leads to a larger question of your view about God” and that view should be “we’re all God’s children.” In case we don’t understand that evaluation of mass slaughter, Woodward translates with a nice gloss: “He wanted war with both practical and moral dimensions.”

Knowing Woodward would spread the gospel in this way, through the Washington Post and best-selling books, the Bush administration turned over many “secret” (that’s what Woodward claims) records to him and Bush gave him several hours of private interviews, including some down on the ranch. When so much stuff is just handed to a reporter, the anticipated quid pro quo is obvious, and that’s why I called this book “pseudo-investigative” journalism.

Woodward introduces us to Bush the intellectual: “I’m not a textbook player, I’m a gut player.”

And Bush the world leader (in response to Secretary of State Powell’s concern that if we extended the war too widely, some of our allies might drop out): “At some point, we may be the only ones left. That’s ok with me. We are America.”

And Bush the democratic leader: “I’m the commander–see, I don’t need to explain–I do not need to explain why I say things. That’s the interesting thing about being president. Maybe somebody needs to explain to me why they say something, but I don’t feel like I owe anybody an explanation.”

And Bush as a leader in domestic affairs: “The war on terrorism is what my presidency is about.”

And Bush the visionary (as seen by Woodward): “His vision clearly includes an ambitious reordering of the world through preemptive and, if necessary, unilateral action to reduce suffering and bring peace.”

Yes, you’ve got to watch out for those Republican humanitarians.

Longtime Observer contributor Robert Sherrill reports on Washington politics and corporate malfeasance.