Book Review

The Gift of Time

By Marcey Jacobson, et al.

“I was making photographs of the world long before I was a photographer,” writes Marcey Jacob-son in The Burden of Time: Photographs from the Highlands of Chiapas.

“Years ago, when I used to ride the subway in New York, I would watch the people sitting opposite me. What else was there to do on the subway? I began to notice that her particular mouth, his particular ear, that chin, that hand, could not belong to anybody else. Every feature was indicative of a kind of character: a stingy nose, a jealous eye. And every set of features fit together into a perfect unity—I call that blood logic. …Whenever I observe a person or a scene, I look for that cohesion. It’s inherent in what I want to photograph. Everything has to fit in, and it does.”

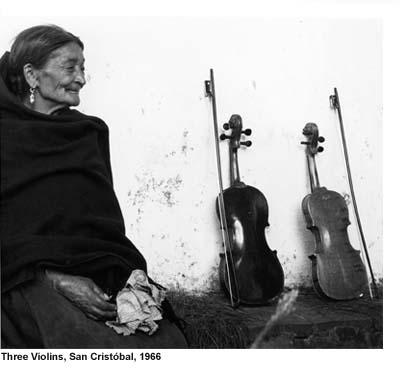

I don’t know about blood logic, but I do know that Marcey Jacobson was blessed with an eye for perfect composition. What else can you say about the photograph called “Three Violins”? Everything fits: the old woman with her Mona Lisa smile, dark rebozo, and perfect posture; the two violins, propped up against the faded wall. Everything has to fit, and it does.

Of the legions of photographers drawn to Mexico in general, and Chiapas in particular, Jacobson is one of the best. Although her pictures have appeared in countless books about the country, The Burden of Time is her first book, published when the photographer was over 90. Editor Carol Karasik produced a labor of love, coaxing Jacobson to agree to the project and then combing through nearly 50 years and thousands of photographs. She also pieced together hours of taped interviews to help shape Jacobson’s essay, a chatty, deceptively simply piece called “Exposures.” (Mexican photographer Antonio Turok wrote the prologue, while Carter Wilson, an American writer living in San Cristóbal, contributed an Afterword,)

The title of the book evokes Mayan mythology—the cycles of days and years carried on the backs of the gods. It also refers to the practice of the cargo, the yearlong financial obligation assumed by members of traditional Mayan communities, and the rapid speed with which tradition is changing or has already disappeared.

In Jacobson’s photos, the burdens are always real enough: A young girl, with bright, questioning eyes carries a sack of beans on her head; a young boy, dressed in rags, totes his fresh-cut calla lilies, like a schoolboy with a backpack; a woman of indeterminate age hustles down the street with a half-dozen chairs strapped to her back. These are all pictures of everyday life; the photographs are spontaneous, nothing is contrived. With each picture, she looks for the connection between herself and the person she is photographing. But her real subject is always time itself; time is everyone’s burden. That’s especially so in Chiapas, with the constant tug of war between change and tradition, between yesterday’s headlines and the very long run of the cycles of Mayan time. “It’s not the purpose of The Burden of Time to show the ravages of the twentieth century or the misery of the human condition,” she writes. “In some ways time is kind. …The saving grace of my life—of most lives—is communion with people, with nature, with something beyond time.”

In September 1956, Marcey Jacobson was a middle aged New Yorker, riding the subway and working as a draftsman, a trade she had been taught during the war. Jobs were plentiful and the work was good. But work, as she liked to say, broke up the weekends. A friend had moved to Chiapas and invited her to visit; she took off on a 10-day holiday. The beauty of the place, along with the parallel worlds of the Mayans and Ladinos, as Spanish-speaking Mexicans are called in Chiapas, intrigued her. Also intriguing was the going rate for apartments in San Cristóbal de las Casas—$4.80 a month, a steal even for provincial Mexico in the 1950s. She decided to stay and do some painting. But the vast expanse of the canvas (“too much freedom”) got in the way. Then one day she was given a Rolleicord camera and Jacobson discovered that she was at home behind it. Soon she taught herself to print and began spending her days slogging through the streets of San Cristóbal and trekking to far-off villages, making pictures of Mayans and Ladinos, festivals and funerals, wizened old men, and ancient ceiba trees.

“At dawn, under the thick layer of fog that enveloped the city, I would see her cool beige figure walking the white meadows, rapt in the landscape,” writes photographer Antonio Turok. “Later at the morning market, while I was having my orange juice and tamales, Marcey would be standing among the vegetable stalls, silent, waiting. It was amazing. She was everywhere, chatting with the vendors or quietly eyeing the scene with uncanny perseverance.”

Uncanny perseverance aside, there is one very obvious gap in her work: Except for a solitary image of a charcoal drawing of Zapatista soldiers sketched on a stone, the Zapatista movement is nowhere to be found. (Nor are there photos of the Mexican army, whose presence in Chiapas increased enormously during the course of the 1990s.) Like most anthropologists, Jacobson failed to read the real writing on the wall.

But long before the Zapatisa rebellion, she had stopped taking pictures of people. Photography had become impossible in several of the villages; communities pushed to the edge by rapid economic and social change, were suddenly faced with the appearance of what Jacobson describes as “hundreds of foreigners dressed in shorts and armed with Kodak’s overtaking the Maya hamlets.”

The Kodak-toting foreigners were symptomatic of the larger social and economic changes occurring in the state—like the Zapatistas themselves. During her years in Chiapas, Jacobson witnessed on the ground a larger, global transformation of traditional, barter societies. Jacobson began to rethink her own relationship with the Highland Maya.

“Why should they tolerate us? Why should they tolerate even the anthropologists?” she asks. “Why should we pry into their personal lives? Because we have such a great need to gather information, to capture and convert?” Jacobson had no pictures of the Zapatistas, because she had decided to take landscapes, skies, and trees instead. The landscapes were all part of the same “dialogue” she sought with people.

At the end of her essay, Jacobson tells a story about a photograph. It’s the story about the photographer’s nemesis: The one that got away. And it captures the essence of Jacobson herself.

She had been out walking one morning when she saw the sun hitting the grillwork on a wall at a certain angle. It was the fifteenth of September, the same date that she arrived in Chiapas so many years ago.

The sun distorted the reflection of the grillwork in such a beautiful way. It was seven o’clock in the morning and I didn’t have my camera with me. “I’ll come tomorrow,” I thought. But the next day it was raining; for several weeks the sky was overcast. “Well, I’ll get it six months later when the sun makes the traverse distance.” But that was the wrong calculation. A year later I went again, on the fifteenth of September at seven o’clock in the morning, and the sky was cloudy. Now I’m waiting for September 15, seven o’clock, this year, and I’ll see if I can catch it. But I’ve been thinking that not only does the sun travel a certain path but also the earth is turning, so maybe the sun is going to be in a different position relative to the earth. And maybe I’ll never get that photo. Or maybe I have to live another 3,000 years to get it.

Marcey Jacobson. She turned 92 last September, and still lives in Chiapas. I have no idea if she got her picture this year. But she will. Even if it takes 3,000 years.