Book Review

Death House Memories

On September 17, I was a media witness to the execution of a 44-year-old man named Jessie Joe Patrick. Two days before, in an attempt to prepare myself for the trauma of watching somebody die, I spoke with Reverend Carroll Pickett, former death house chaplain at the Walls Unit in Huntsville. I had been reading Pickett’s memoirs, devouring each page for details about the process of capital punishment. Pickett is one of the few people who can relate from intimate experience what happens on an execution day. From 1982, when constitutional capital punishment returned to Texas, until 1995, when he retired from the Department of Criminal Justice, Pickett was the humane face of the Huntsville execution team. Over the course of those years, he helped 95 men make their final arrangements and confront the reality of their imminent demise. Then in 1995–after years of ambiguous silence–he decided that “killing to prove that killing is wrong turns logic on its head,” and became an opponent of the death penalty. When I told him that I was going to witness an execution, he conveyed a piece of advice: “The more you see, the more you don’t want to see.”

Pickett’s memoir–as told to award-winning non-fiction author Carlton Stowers–helps us to see some of the secretive workings of contemporary capital punishment in Texas. December 7 marks the 20th anniversary of the resumption of capital punishment in this state, and yet after all those years, we still know little more about the execution process beyond the information that Associated Press reporter Michael Grazcyk dutifully files in a series of formulaic stories. The state shields the identities of the executioners, both legally and literally in the death chamber. (“Somebody” administers the fatal drugs from behind a one-way mirror.) Corrections employees who volunteer to carry out an execution are silent about their experiences. In fact, since the participants in National Public Radio’s 2000 documentary, “Witness to an Execution,” received so much hate mail from Europe, it is now almost impossible for journalists to interview those who operate Texas’ machinery of death. (See Afterword, page 30.) Consequently, there is great value in Carroll Pickett’s documentation of his career as death house chaplain. As contemporary history, his memoir is valuable reading for those who want to know how Texas continues to deploy death as a strategy of punishment.

Since Pickett is now an abolitionist, his book tries to chip away at the state’s unthinking reliance on capital punishment. As he explains, he retired in 1995 because the ever-increasing execution rate served only to detract from his ministry as prison chaplain. When the state began administering lethal injections in 1982, the staff at the Walls Unit were not prepared and seemed genuinely shocked. But by 1995 executions had become routine; in the past 20 years, over a third of all legal executions in the United States have taken place in Texas.

Pickett’s description of a singular night when two men were put to death is horrifying. While the hour of the first man’s execution was fixed according to tradition and routine, the warden left it to the chaplain to decide when the second man would be moved to the lethal-injection gurney. That experience helped push him into the camp of those opposed to “state-sponsored murder.” As Pickett emphasizes throughout the book, executions affect everybody involved in the process and each execution creates new sets of victims–guards, administrators, family members, and witnesses. After years of working for the prison system, he now concludes that capital punishment should be abolished because it serves political ends rather than promoting justice. He reminds us that since 1982 the population of death row has increased; the state’s homicide rate goes unchecked, while politicians run on death-penalty platforms.

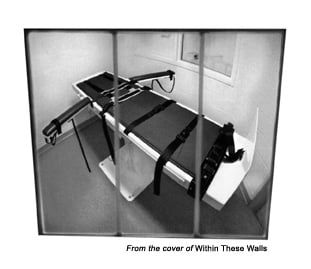

Unfortunately, Pickett fails to analyze his own significant role in crafting the legitimacy of capital punishment in Texas. In 1982, when the State of Texas executed Charlie Brooks, Jr., only one member of the prison staff had ever witnessed an execution–an electrocution in the 1960s–and knew what to expect of the inmate. From December 7, 1982, Pickett’s job required him to make sure that the condemned man was familiar with the fatal procedure and to act as a liaison with family members, lawyers and the prison staff, providing them with guidance and support. He quickly became the expert on how a team of people–of which he was a part–could kill a person “humanely.” His concern for the well-being of the condemned led him to write Texas’ execution protocol (The Team Concept of Execution), which, as he himself reminds us, other states began to use when they adopted lethal injection. The chaplain’s role in crafting the execution procedure helps explain in some small part why lethal injections are entrenched in this state. And Texas’ “successful” pioneering use of the lethal-injection gurney has now led to its adoption by a majority of the death-penalty states.

This is part of the big picture, which Pickett curiously seems to miss. (For the record, the book contains no discussion of death-penalty jurisprudence, either.) Instead he focuses his criticism on those outside of the execution process who appear on execution day to comfort the condemned. In several passages, Pickett questions the motivation of women (in his account they are almost all women) who arrive to speak with the inmates in their final hours. To Pickett, these women act as they do because of a macabre emotional attachment, rather than an ethical abolitionist stance.

“In the years to come, I would see similar attachments between convicts and women in the outside world. And always it was far easier to understand the position of the isolated and lonely inmate, starved for female contact, even in the form of a letter or a few hours of quiet conversation on visiting day, than the position of the women. I could only assume that they developed some kind of strange fascination with a world of which they had no firsthand knowledge, one filled with danger and socially unacceptable behavior. In some way, I suppose, befriending a Death Row prisoner provided a safe, romantic thrill absent in their day-to-day lives.”

He is also exasperating to read when he does decide to go beyond capital punishment and probe the workings of the prison system in general. He provides a brief history of the system from a prison administrator’s perspective. He attests to the difficulties of operating a large-scale prison system with any degree of compassion, given the overwhelming expansion in Texas’ prison population over the last decade. Strangely, he believes that those who administer the prison system are their own best guardians, and repeatedly criticizes Ruiz v. Estelle, the lawsuit that placed Texas prisons under federal oversight for 30 years. He insists that that Ruiz actually made life worse for a great many inmates, that “compassionate care” was a casualty of the demise of administrative flexibility–rule-bending–under the terms of the lawsuit. William Wayne Justice, the federal judge who wrote in an impassioned opinion that it was “impossible to convey the pernicious conditions and the pain and degradation which ordinary inmates suffer” within Texas prisons, is a mere interloper to Pickett. “The best intentioned politicians and lawmakers simply do not understand the unique social structure that exists behind the bars and brick walls,” he writes.

Pickett refuses to recognize that Justice sought progressive change, attempting to place rehabilitation on a surer footing by guaranteeing inmates’ civil rights. Instead he offers a different, more sinister, and yet perhaps more honest, interpretation of incarceration in Texas: Rapists and murderers must forfeit their civil rights when the state places them in prisons, he writes. Unfortunately, in his eagerness to criticize Justice, he forgets that advocates of legal execution use similar arguments to justify the death penalty.

Pickett readily admits that in the years when he ministered to those who were soon to die, he never opposed the death penalty. He has since become an eloquent death-penalty opponent, speaking at moratorium meetings and sometimes granting interview requests. His memories of each and every inmate he helped execute remind him of the time when his job required him to craft an execution protocol now used to kill people in many other states. Consequently Within these Walls demonstrates that each execution creates more victims, increasing the number of stories of loss and suffering. His message of compassion denied is a powerful one, required reading for those who currently support the death penalty, or are ambivalent about its effect. As such, Pickett’s book is a welcome addition to the growing abolitionist literature.

And he was right, by the way. After watching an execution I realize that the more you see, the more you don’t want to see.

Patrick Timmons is a history doctoral candidate at UT-Austin where he studies the death penalty in nineteenth century Mexico.