Shut Out

The Dems Strike Out . . . Again

On the Sunday morning before the November 5 election–near the finish of his second unsuccessful run for lieutenant governor–John Sharp attended services at the Cornerstone Church in San Antonio. The designated Anglo on the Democratic “dream team” ticket, Sharp is credited with helping to convince Tony Sanchez to run for governor. According to the plan, Sanchez, a South Texas oil man and banker, would finance the effort from his considerable fortune, estimated to be in excess of $600 million. The Sanchez surname would bring out a tide of Hispanics to vote for Democrats. Ron Kirk’s candidacy for the U.S. Senate would spur African-American turnout. With Sharp drawing the Anglos, they would have enough votes to take the lite gov position, if not more.

Neither of his ticket mates joined Sharp in the enormous auditorium, a shrine to politically savvy modern American fundamentalism. The 5000-seat church is located on Cornerstone’s 35-acre campus, whose grounds include a school, a television station, and 13 acres of parking. The church’s broadcast arm, Global Evangelism Television, Inc., claims to reach 92 million homes weekly worldwide.

Sharp was not the only politician hungry to get his face before Cornerstone’s live audience and circling TV cameras. Kirk’s rival John Cornyn was also present, as were over 30 down ballot candidates. Although Cornerstone declares itself to be nondenominational and bipartisan, most of the candidates in attendance, unlike Sharp, were Republican. Placed on tables outside the mortuary-clean sanctuary were stacks of Christian Coalition voting guides ready for distribution. Needless to say, the dream team did not score well with the coalition.

An assistant pastor introduced the first hymn of the morning by noting its appropriateness on the eve of the election. And with that, the racially mixed congregation launched into the evangelical standard, Trust and Obey:

Trust and obey, for there’s no other wayTo be happy with Jesus, but to trust and obey.

After the singing and a call to tithe, Rev. John C. Hagee, Cornerstone’s founder, pastor and television host stepped down off his throne, stage right, and moved to the center podium. He called for registered voters to raise their hands, and noted approvingly that the count revealed 100 percent. Hagee introduced the candidates individually. Most every one received a close-up on the giant television screens mounted above the stage. Then, as in churches across the nation, the congregation prayed over the candidates, asking God to pay attention.

With that formality dispatched, Rev. Hagee launched into the morning’s sermon, entitled “In God We Trust.” These are heady days for Hagee, an author whose books–titles like The Beginning of the End and Final Dawn Over Jerusalem–are fixtures in Christian “pre-apocalyptic literature.” Hagee told the Los Angeles Times that “I believe World War III actually began on September 11, 2001.”

As Sharp stood listening along with the congregation, the reverend gave voice to a political worldview perfectly in tune with Republican hardliners Tom Delay and Trent Lott. Democracy in America is being hijacked by activist federal judges. Politicians robbed the nation’s brave soldiers of a win in Vietnam. Israel is America’s only friend in the Middle East. Our God is not Allah! The ACLU is un-American. The “military” is going to crush terrorism in these United States. Hagee asked, “Do you remember when welfare was a state of being, not just a check to a deadbeat?”

The congregation applauded every punchline, but it was Hagee’s impassioned plea to ban abortion that drove them to their feet. “Forty million innocent lives have been lost,” he thundered. “Pay day will come!”

As the crowd cheered lustily, standing among them, clapping in the front pew was John Sharp. Outside the chapel, anyone could read on their handy Christian Coalition guide that this particular candidate opposed a ban on abortion.

Just how ironic Sharp’s Faustian bargain would prove to be, became clear Tuesday night. The carnage was readily apparent by 10:00 p.m., when the bar serving the Sanchez victory party at the Austin Hyatt ceased to be free. Sanchez likely spent upward of $100 million of his own money this election season. Nonetheless, Republicans in Texas won every statewide office and control of every branch of government. The Democrats relinquished a reign over the house of representatives that dates to the 13th Legislature in 1873. Worse, the size of the loss–88 seats to the Republicans–ensured the election of radical right favorite Tom Craddick as speaker. The once evenly split senate became solidly Republican, helmed by the new lite gov, David Dewhurst, an odd social conservative loathed by senators on both sides of the aisle.

Apologists for the Texas Democratic establishment point out that losses in the Lone Star State mirror those across the country. They talk about how recent events–insecurity from 9/11, the Iraq debate, and the sniper killings–kept the electorate distracted from their core economic issues. They note that Anglos across the South have deserted the Democratic Party. The boldest among them blame the malaise on the party’s rudderless leadership in Washington, D.C.

Locally, their initial plan to market Tony Sanchez as a centrist businessman who would rescue the state from politicians fell apart in a post-Enron environment. Suddenly politicians were called on to save the country from businessmen. The more ungrateful privately grouse at the baggage first-time candidate Sanchez brought with him into the race, from money laundering charges to a scant history of voting. Others begrudgingly admit the Republicans played a near perfect game–from registering new voters to grassroots turnout–behind a popular president from Texas. Some even blame the rain that soaked the state during early voting. Finally, nobody expected Rick Perry to accuse their candidate of murder, on television, as often as every half hour some nights.

While all of the above is undeniably true, the scale of the thrashing Texas Democrats received at the polls exposes a campaign whose defeat was in part self-inflicted. At its root was a strategy that had more to do with calculation than principle, based on faulty ethnic assumptions, in an operation where the quantity of money magnified rather than minimized errors. In particular, the Sanchez campaign earned a deserved reputation as the Waterworld of the 2002 political season, an expensive debacle that capsized an already leaky Texas Democratic Party.

“The Republicans were on a crusade,” observes Andy Hernandez, a political science professor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio. “The Democrats were on a campaign.”

In his campaign office a month before the election, State Rep. Garnet Coleman showed off the latest mailer he helped put together. Coleman ran what proved to be the unsuccessful Democratic coordinated effort (Team Texas) in Harris County. For weeks, he subsisted on coffee and cigarettes, which he consumed between answering phone calls, e-mails, and faxes. Piled on a table were the mailers. “Fighting for Fairness, Fighting for Families,” proclaimed one.

The Democrats were counting on efforts like Coleman’s to produce high turnout in urban areas, especially among minorities. The debate over how many Latinos came to the polls and for exactly whom they voted, as of press time, has yet to be resolved. A lack of exit-polling data keeps the picture somewhat blurry. Clarity will come from a more detailed and time consuming analysis of heavily populated Latino voting precincts. It makes sense that as the size of the state’s population of Latinos has broken records, so would their voter turnout. But exactly what percentage of the Latino vote went to each party will likely be fought over for some time.

For Democrats, the data on who they contacted and whether that person voted is available. It’s likely not a pretty picture. Both the Party and the Sanchez campaign spent considerable time and money identifying voters, particularly Latinos. It is something even politically tone deaf people can do. “Targeting is a science,” noted Coleman. “Winning hearts and minds is more of an art.”

Overall only 35 percent of registered voters statewide bothered to cast a ballot. According to a map on Harvey Kronberg’s website (Quorumreport.com), turnout was 36 percent or less in San Antonio, Corpus Christi, McAllen, and the Houston area. Most of South Texas came out heavily for Sanchez, although in a telling rebuke, Hidalgo County and Cameron County gave slightly more votes to his running mate Kirk. (Perry managed to steal 31 percent and 39 percent respectively in each county. He tied Sanchez in Nueces County.) But huge populations of Latinos live in Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. To offset their lack of Anglo support, Democrats needed a record minority vote in these urban centers populated by hard to reach recent immigrants, to complement a surge in South Texas, where the demographics trend toward young and non-political. It appears the urban minorities didn’t deliver crusade-like numbers. Since Anglos represent 70 percent of the electorate, even a slight gain in their turnout unmatched by minorities is fatal. Anglos turned out in high numbers, and they voted overwhelmingly for the GOP.

Under way now is much hair pulling among Democratic Party leaders over why minorities failed to embrace the ticket. It’s important to turn that question on its head. While the candidates on the ticket were fond of mentioning that together they looked like Texas, the men behind the curtain did not. Anglos almost exclusively sat at the top of both Team Texas and the Sanchez campaign, men like Sanchez campaign manager Glenn Smith, political operative Peck Young, and negative media guru George Shipley. The Democrats who went home with the most money, either by producing and placing television adverts or funneling dollars to ground troops, were Anglo. The dominant messages (or lack thereof) were crafted by Anglos. “You wonder why these consultants don’t do better with working-class Anglo voters,” muses Andy Hernandez.

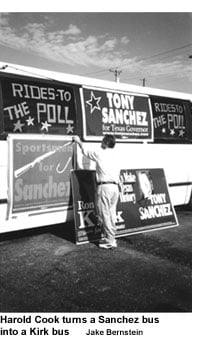

The Democrats spent little time trying to convert working-class Anglos, particularly women, who might yet be susceptible to an economic populist message. (To their credit, the Sanchez people feinted half-heartedly at a “Sportsmen for Sanchez” campaign that tried to do just that, but it never graduated beyond bumper stickers, yard signs, and other gimmicks. There were no loud policy pronouncements on, for example, public access for hunters or any other concrete proposal.) Instead they chased after the myth of the sleeping giant. Under this story line, Latinos–only a few decades away from being a majority in the state–will vote like African-Americans en masse, and most always for Democrats. There seemed to be little acknowledgement from the Democratic side that everybody needs to be given a reason to support a candidate, no matter the ethnicity. “There was no sense of needing to persuade,” marvels one Sanchez insider.

Others are skeptical that Latinos will ever vote in bloc, even if there is a Latino candidate. “An African-American model to get Hispanic turnout is not going to work,” says James Aldrete. One of the few Hispanic consultants who worked for the statewide ticket, Aldrete fashioned direct mail messages, primarily for South Texas Latinos.

Interviewed less than 10 days before the election in his South Austin office, Aldrete noted that while Latinos might vote for Sanchez in the end, they need cover because they value independence. Furthermore, nationalized and first generation immigrants don’t have built-up resentments. “Hispanics want to believe that race doesn’t matter,” he says. “They don’t face the same assimilation problems blacks do.”

Much of the campaign literature put out by the Democrats focused on the fact that the ethnic composition of the ticket was historic, its inclusiveness an automatic guarantor of fairness. It’s not a message that necessarily works for Latinos, particularly in South Texas and San Antonio, where there are plenty of elected officials who look like they do. “‘Help make history’ is an African-American line that works with older folks,” said Aldrete.

Rather than go that route, Aldrete filled his mailings with policy positions and efforts to make the candidates more approachable by stressing working-class roots. “They say we don’t vote. This year we have more reasons to vote than excuses to stay home,” proclaimed a mailer that Aldrete jokingly refers to as “the Catholic guilt piece,” destined for registered Latino family households. It’s not in Spanish, nor does it mention ethnicity, but the faces on the front are clearly Latinos. The mailer lists seven reasons why they should vote, from “[Sanchez and Kirk] are fighting to expand health insurance coverage for children” to a pledge to keep social security out of the stock market.

But grassroots activities like Aldrete’s direct mail, a good candidate stump speech, and literature drops were overshadowed by the barrage of negative television commercials. One Democratic field commander likened it to being killed by friendly fire.

There is no question that television in a huge state like Texas can reach the most people. And common campaign wisdom says one must go negative to unseat an incumbent. By the same token, it is believed to be political suicide not to answer attacks. This advice happens to be somewhat self-serving. Consultants spent tens of millions of Sanchez’s cash on television buys, pocketing a standard 15 percent commission in the process. But unfortunately for their client, it was a game he could never win.

Sanchez needed record turnout, but negative ads only convinced an already apathetic electorate to stay at home. And the candidate presented more negatives to exploit than Perry did. Unlike Sanchez, the Perry campaign had surrogates deliver their worst attacks, providing a thin insulation around the governor. In a brilliant twist, the commercial accusing Sanchez of being an accomplice to the murder of a federal agent (by laundering drug money in his bank) featured Hispanic ex-DEA agents as spokesmen. None other than primary opponent Dan Morales worked to spread the outrageous charge that because of Sanchez’s support of affirmative action, the Laredo banker was out to get Anglos. Money laundering accusations and a lack of prior political involvement played into existing fears of Latino voters that they would embarrass themselves by “making history” with Sanchez.

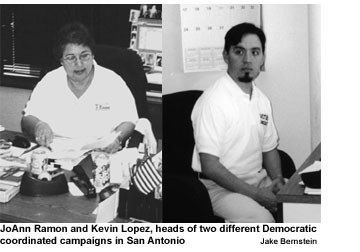

“Hispanics think he did something bad to make all that money,” reported JoAnn Ramon, who ran the street operation of one of two Democratic coordinated efforts in San Antonio.

The volume of Sanchez and Perry ads all but drowned out the attempts of other candidates to put their messages before voters. Meanwhile, Sanchez was so busy attacking, he didn’t present an alternative. Did Tony Sanchez write a single opinion piece for a newspaper? The only issue that Sanchez managed to corner during the campaign was insurance. (Perry deflected even this by pretending to clamp down on Farmers Insurance.) “If you ask what’s the difference between Sanchez and Perry on economic issues, nobody can tell you,” notes Hernandez.

When Sanchez did attack, he not only failed to use surrogates, he failed to connect. Rick Perry vetoed 82 bills at the close of last legislative session. Sanchez had the money to do infomercials for a year leading up to the election on the solid bipartisan legislation Perry killed. Instead, Sanchez attacked Perry solely for taking contributions from special interests affected by the legislation. The campaign included a fancy faux-movie poster entitled “The Sum of All Vetoes,” and a television commercial that ripped off M

sterCard. But it didn’t stick.

For already skeptic

l Anglos, the Democratic strategy converted the dream into a stereotype. Every Republican from Karl Rove down knows that what some Anglos dislike about affirmative action is their perception that it’s unfair; that based on some quota, the undeserving receive something that rightfully belongs to the deserving. (Cornyn played on this by wrongfully accusing Kirk in commercials of being “not ready.”) The dream team was an explicit quota, but it didn’t have to be. The players on the team were capable and knowledgeable men. The only novice, Sanchez, showed a willingness to listen and to learn essential in a successful politician. That reality didn’t make it past the barrage of negative ads from both sides. The Sanchez campaign–setting the tone for the entire ticket–failed to produce any real policy alternatives. Voters quickly grew weary of platitudes devoid of specifics, like “scrub the budget” as an answer to a $10 billion deficit. With help from the Republicans, the message that trickled through for Anglos was that once again, minorities were asking for promotion without proving their worth.

It was a little before 6:00 p.m. on election day in San Antonio at the Sanchez headquarters, a giant, empty showroom off the highway. The final push was on, and the atmosphere was chaotic. At least 100 people, mostly teenagers milled about, most working, others socializing. On one side, phone bankers dialed and pleaded. Across the room, workers set up two kegs for the victory party. Rows of empty chairs faced a giant television screen. Christian Archer, who spent the last few months of the election running the ground operation, shouted into a phone and walkie talkie almost simultaneously. Archer fielded calls from precincts about voters who needed rides or were encountering difficulty in casting their ballot. Amidst the anarchy, one of Archer’s young field workers approached. “We’re going to do this again tomorrow, right?” he asked. Archer stared in disbelief. “No,” he replied weakly.

Some Democratic leaders cynically never thought Tony Sanchez had a chance to win. Instead they hoped his money and presence on the ballot would help those, like John Sharp, below him. When the final results were tallied, Sanchez lost to Perry by 18 points. Few Democrats in competitive races could escape being swamped by a rout that large.

In the end, Democrats tried everything. Sanchez alone ended up spending at least $40 per vote. In addition to the massive, albeit self-defeating media campaign, they also mounted an enormous field operation. Millions of pieces of literature arrived in mailboxes across the state. Thousands of paid “volunteers,” mostly youngsters below voting age, canvassed homes looking for people who leaned Democrat. An unprecedented number of live and automated phone calls were placed.

“This has been the biggest, largest ground war ever waged in Texas by the Democrats,” boasted Archer. “We’ve never been able to fully fund this kind of effort across the state.”

There is nothing more important to the survival of the Democratic Party than a strong grassroots operation. Yet it’s also the hardest to accomplish, particularly with the low-income people who are the Democrats’ base. “It’s hard getting people into the system,” says Claudia Flores, who helped Team Texas with Latino turnout in Houston. “They are hesitant in getting involved. They don’t think it makes a difference. That’s the perception you have to overcome.”

Without doubt, the Sanchez field operation’s Achilles heel was its lack of message. The money available only made it worse. The Sanchez campaign, no doubt taking a cue from its candidate, was marked by a corporate ethos that many say robbed it of the passion necessary for a political campaign. The readily available money encouraged greed, and a surfeit of trinkets–from rain ponchos to backpacks–gave the campaign the feel of a giveaway, not a movement. “There was a backlash to so many ads,” recalls one Sanchez field worker in East Texas. “Too many phone calls, too many signs, but there was no real message.”

Although the Sanchez campaign could take pride in the energy of the young staff it sent into the streets to spread the word about their candidate, these paid volunteers might not have been the best ambassadors. Most didn’t know or care about the issues and did nothing more than leave door hangers. They also learned, mistakenly, that working political campaigns is more about getting paid than changing the world. “If the contacts are not motivational, it doesn’t matter,” notes Rep. Coleman.

Archer didn’t take over the field operation in San Antonio until September. It was indicative of a campaign that began way too late. All spring and summer, the Sanchez consultants kept their candidate under wraps, confining him mostly to his home base in Laredo, as if they had something to hide. Meanwhile, Perry traveled through the state bestowing pork and campaigning on the public’s dime.

“They were 10 points behind in the summertime and there was no sense of urgency,” recalls one Sanchez staffer. “They told [Sanchez] nobody pays attention until Labor Day, but that is exactly why you use that time to motivate people who do pay attention, so they can generate buzz.”

Sanchez could have used that time to build relationships in communities where he needed votes. In San Antonio, the drink of choice at the headquarters was Starbucks coffee. Beyond being overpriced, it was symptomatic of the campaign’s failure to reach out to small businesses.

“Sanchez missed a golden opportunity,” opined Kevin Lopez, who along with Laura Barberena ran the other coordinated campaign for the Democrats in San Antonio. “He could have hired people to help him build human relationships, instead of a sterile, corporate relationship.” Lopez continued, “His biggest strength was his colloquial Spanish and they took it away from him.”

Originally the Democratic strategy had clearly delineated tasks for each campaign on the ticket. In particular, it was the job of the coordinated campaign (Team Texas) to turn out the base. The Sanchez people focused on “swings,” Democrats or independents who leaned toward the party but lived in precincts that didn’t overwhelmingly vote that way. The concentration on swings, which is essential to rebuild the Democratic Party, may have backfired horribly. It’s quite possible many of the swings cultivated by Sanchez voted for Perry.

Meanwhile, Team Texas subcontracted their work to regional surrogates, mostly state representatives. Not only did this leave pockets where nobody had responsibility, but the ready availability of money exacerbated local tensions. In San Antonio, a feud between Congressman Charlie Gonzalez and State Sen. Leticia Van De Putte created the need for two coordinated campaigns. Here, too, the problems inherent in treating Latinos as a bloc became evident. JoAnn Ramon, Van De Putte’s field operator, concentrated her efforts in getting out the base vote on the solidly Democratic westside of San Antonio.

“We are telling them we need Tony Sanchez to open the door a bit more,” said Ramon during the campaign from her staging ground at a downtown used car lot. “We have to remind ourselves of who brought us.”

Ramon admitted that her approach, which is classic urban minority machine politics based on family relations, wouldn’t necessarily work with young, educated or affluent Latinos. Ramon’s home precinct is a case in point. “My neighborhood is swing,” she explained. “They don’t realize they are Latinos. They think they are Mexican Americans.”

Kevin Lopez and Laura Barberena focused their energy on swings. They said that they sent a mailer to Ramon’s own son, who hasn’t voted regularly. The two operated out of a storefront on the southside of San Antonio. Just as James Aldrete did, they concentrated more on the issues and on finding creative ways to pitch the entire ticket to those with less party loyalty. One of their more successful mail pieces posed as a tongue-in-cheek thank you letter to Republicans. Unfortunately, some swings that they contacted likely voted Republican.

“Any campaign, first thing you do is lock down your base,” said Lopez. “They assumed they had their base locked down.” From early voting in most places it became clear that the coordinated campaign, which had only finalized its budget a few weeks before, was underperforming. The Sanchez campaign switched gears and started to send its workers into heavily minority base precincts to get out the vote. In San Antonio, Christian Archer labeled one such push Operation Rolling Thunder, sending hundreds of kids into JoAnn Ramon’s territory with 1,000 yard signs and sound trucks urging people to vote. With the heavy artillery, voting went up, but not enough.

There are any number of people putting a brave face on defeat right now. Those who ran the campaign are hunkering down under the inevitable criticism. “I fully sympathize with people who want to find a villain who was behind this,” says Glenn Smith, Sanchez campaign manager. “But the fact is we got swamped by a national fervor over George W. Bush, domestic security, and national security. No Democrat was going to survive that.”

Some, like Garnet Coleman, believe that the precedent of running a Latino for governor and an African American for U.S. Senate were major breakthroughs that must not be underestimated. “The field is plowed and the seeds are planted for the next person,” he says.

Many point to young people within the campaigns who received valuable experience they can now apply in the future. A few note the emergence of a handful of Latino consultants like Aldrete and Lopez.

But happy talk about the benefits of this campaign might be overblown. “They didn’t leave an infrastructure there because it’s all based on money,” says Andy Hernandez. “It’s not based on issues or values. When the money is gone, it’s gone. If they had used 10 percent of the money, they could have built a groundswell on core issues.”

Others believe that the scale of the blowout and the quantity of money invested will force the Texas Democratic Party to face its weaknesses and adapt quicker than it would have under the circumstances of a slower decline. Nobody can claim there wasn’t enough money this time. “We act like a major league player who got sent down to the minors,” observes Harold Cook, who was the paymaster for Team Texas in San Antonio. “Instead we should be like a hungry minor league player on his way to the majors.”

And indeed, the discussion has begun. “I think the Austin Democratic white political consultancy has an approaching credibility problem,” wrote a Texas-based union organizer after the election to several of those involved in the campaign. “White folks cannot be the exclusive stewards of this party anymore. We cannot appear to be running people of color for office and not embrace the development of their consultancy and political skills. We have to diversify.”

Maybe the sleeping giant does exist. Maybe it’s not just Latinos, but people of every color who are screwed by cold-blooded extremist Republican policies. Waking that giant will take organization, education, and mobilization. It must come from communities around the state, not just Austin. And these are not activities that will enrich consultants. As fate would have it, Texas Democrats appear to have plenty of time to prepare, for they didn’t just get sent down to some triple A farm team. It looks like, because of Bush’s popularity and redistricting, they are doomed to at least four, if not ten, years in the rookie leagues.