Please Excuse Their Mess

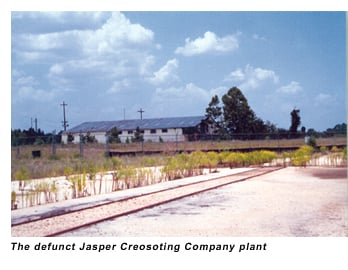

The defunct Jasper Creosoting Company plant lies on 11 lilting acres cleaved from pine forests that surround the small East Texas town of Jasper. From 1946 through 1986, the plant processed and treated wood for utility poles and railroad ties using creosote, a carcinogenic compound that, with prolonged exposure, can cause cancer. In milder doses, it can result in skin burns, vomiting, breathing problems, convulsions, and hypothermia.

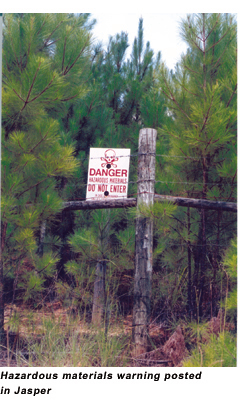

The site is barren now–just patches of fenced-off fields, a swath of concrete, and old freight rails vanishing beneath the weeds. If not for the skull-and-cross-bones signs installed by the Environmental Protection Agency warning of buried hazardous chemicals, the place would seem harmless, and many of the low-income residents living near the old plant think it is. Some don’t know their houses lie yards from a den of festering contaminants slowly saturating the soil and water table–pollution that, if not halted by the EPA Superfund program, could poison their drinking water. Even fewer residents realize a cleanup of the area has stalled. The EPA is struggling to secure funding for the project, one among dozens of Superfund sites around the nation shortchanged by the Bush Administration.

How much creosote and other chemicals were leaked into Jasper’s soil and water during the plant’s 40 years of operation is unknown. As Jasper city manager David Douglas gently put it, “Forty or fifty years ago, they didn’t handle these products with the same level of care that we do now.” In fact, prior to 1965, according to EPA documents, creosote openly seeped into a ditch at the site, and the plant hemorrhaged the carcinogen into the soil and a nearby wetland for decades, as did its sister site, the Hart Creosoting Company plant a few miles away on Jasper’s south side.

Approximately 11,000 people in the area get drinking water from wells drawn off the now-imperiled Jasper Aquifer. One of the city’s three municipal drinking water wells sits on a hydraulic down-gradient just three-fourths of a mile from the Jasper Creosoting site. And EPA officials concede they don’t know how contaminated the ground water is since they haven’t studied it. The last survey, in 1998, found ground water-pollution 50 feet below the surface, far shallower than most area wells. But with few natural barriers in the soil, the creosote may have pushed much deeper by now. Regional EPA officials say they have a ground-water study planned, but don’t have enough money to conduct fieldwork.

Despite the ground-water threat, the Jasper and Hart cleanups had their funding cut entirely this year by EPA headquarters, part of the Bush Administration’s decision to slash money for 33 Superfund sites around the country. The cuts were made public, and sparked a controversy, when Democratic congressmen leaked an EPA inspector general report to The New York Times in late June.

Before its funding dried up, the cleanup at Jasper Creosoting had progressed well. The EPA Region 6 office in Dallas, which oversees the site, had removed the plant’s most contaminated structures and soils, temporarily stabilizing the site and reducing the immediate public-health threats. But ground-water contamination was still a concern, and last September the regional office prepared plans for a final cleanup of the two sites. EPA documents show the regional office requested more than $16 million for the cleanups. But in the past year, EPA headquarters hasn’t granted a dime of the requested funding. EPA officials in Dallas hope the money will come soon. While they wait, work in Jasper has halted. Meanwhile, the partially cleaned-up plants continue to drip hazardous chemicals into Jasper’s soil and water.

Much of Jasper looks and feels rundown. Statistics from the 2000 Census tell the story. Nearly 20 percent of all Jasper County residents, and a shockingly high 28 percent of children, live below the poverty line. The average annual income in Jasper is $28,900, almost $6,000 below the state average, with 17 percent of households earning less than $10,000 a year, and nearly a quarter of families subsisting on less than $15,000. The poorer sections of town appear oddly rural, with crumbling houses, trailers, and shacks almost melting into patches of forest. These are the areas most exposed to decades of creosote poisoning. Both the Hart and Jasper plants are in poor minority neighborhoods. It is impoverished communities like these, where many of the nation’s most contaminated sites are located, that are most dependent on the EPA’s Superfund program.

Passed in 1980, during the waning months of the Carter Administration, Superfund was a revolutionary environmental program. It identified the nation’s worst contaminated areas, tracked down the responsible companies, and made them pay for the cleanup, a philosophy known as “polluter pays.” If the guilty company was out of business or couldn’t pay for pollution removal (what EPA terms an “orphan” site), the government paid for the cleanup using a Superfund trust fund that, in the past, was financed through a special tax on the chemical and petroleum industries. After a rocky beginning, the program first made headway in the late 1980s and, with millions of dollars pooling in the trust fund, EPA started sweeping away the detritus of America’s industrial age.

Conservatives hated the Superfund tax on chemical and oil companies. And in 1995, the Republican-controlled Congress eliminated the tax and with it, the lone source of funding for orphan Superfund sites. Its revenue stream gone, the trust fund has shrunk from roughly $3 billion in 1996 to a projected $28 million next year (critics predict the fund will be broke by 2004). While the trust fund vanishes, the program’s costs are rising, with many projects entering the final, most expensive cleanup phase. To compensate for the disappearing trust fund, the White House has budgeted more money for Superfund in recent years, though not enough to avert a cash crunch at the EPA.

The Jasper sites have been prime victims of the funding shortfall. By the early 1990s, the Hart and Jasper sites caught the attention of the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (now named the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality) and the EPA. In 1995 and 1996, the Region 6 office in Dallas began the cleanups by stabilizing the two sites, dismantling buildings and storage tanks, and carting off the most contaminated soil and sludge. Much of the remaining hazardous material, nearly 95,000 cubic yards of it, was buried in nine-foot-deep, clay-capped temporary waste cells at the sites, designed to contain pollutants until the extensive, permanent cleanup could be planned and funded. But problems persisted. The waste cell at the Jasper Creosoting plant began to erode and highly hazardous creosote-soaked soil leaked downhill into a drainage pipe that runs off-site toward a nearby wetland. So EPA conducted a second temporary cleanup from November 1999 through January 2000 to shore up the cell and head off imminent threats to public health. That was nearly three years ago, but the erosion and leakage continues. Much of the soil at the Jasper plant seems to be collapsing. Sinkholes litter the site, and the fenced waste cell is tilting noticeably downhill into a drainage pipe that has visible streaks from recent runoff. “We’re aware that the cell is eroding,” said Bob Sullivan, EPA Region 6 remedial project manager for the Jasper sites. “EPA [knows] there is potential for release from the cell.” Sullivan says the problems with the waste cell are not surprising since it’s intended as a temporary solution, pending the final cleanup. Now, lack of funding from the Bush Administration threatens to delay that final step. Sullivan says the regional office may consider a third temporary action if funding doesn’t come through and the situation worsens.

While surface water contamination has been found in creeks near both sites, the main source of worry in Jasper continues to be creosote poisoning of ground-water. The Jasper Creosoting plant sits within four miles of 27 wells, which range in depth from 22 feet to 800 feet. The closest of those is the City of Jasper’s municipal well, which lies in the path of the leaking waste cell, according to EPA documents. That well is one of three in the city water system, which supplies drinking water for more than 7,000 people. At the Hart site, 39 wells are within four miles of the contamination. EPA and TNRCC last studied the ground water in late 1997 and 1998, and found an “observed release” of contaminants into the ground-water at both the Hart and Jasper sites, according to EPA records. At that time, the contamination was just 50 feet deep, not close to the Jasper city well depth of more than 800 feet. But Sullivan notes that the soil contains few obstacles to halt the creosote, a compound known to migrate.

Jasper city manager David Douglas says the city tests its wells monthly for creosote contamination and has found nothing. But Sullivan concedes EPA isn’t sure of the extent of the contamination. To find out, he said, the regional office needs funding from EPA headquarters.

Therein lies the conundrum for the EPA regional office. In the face of its Superfund cash shortage, EPA developed a ranking system that assigns each site a risk-analysis score to ensure the most dangerous sites get funding first (it’s known as an HRS score). The key factor in this calculation is threat to human health. The Jasper and Hart sites respectively scored 50.0 and 48.03 out of 100, which is well above the Superfund cutoff of 28, but apparently not high enough to leverage precious dollars from EPA headquarters this year. The trouble is, EPA records show potential ground-water contamination wasn’t fully factored into the Jasper sites’ HRS score. It can’t be accurately measured without a further ground-water study. This puts the Region 6 office in a Catch-22 of sorts, since it needs a ground-water study to raise the sites’ HRS score and have a better shot at funding, but it needs funding to study the ground-water and raise the HRS score.

So no one can say definitively if the Hart and Jasper sites threaten public health in Jasper. The Texas Department of Health studied the sites in 2000 and found they pose “no immediate threat,” but concluded the public health hazard is “indeterminate” because its study didn’t include ground-water contamination or solvency of the waste cell, the two areas of greatest concern. Douglas was diplomatic when asked about the threat. “This is not something we’ve been totally upset about,” he said during an interview in his Jasper office. “Our water source is secure. But we can’t help but be a little nervous because the potential for contamination is there. We’re a little apprehensive about these sites and we’d like to see them taken care of.”

Everyone involved wants the sites cleaned. When that will happen remains anyone’s guess. The Region 6 office is preparing remediation plans, and the EPA’s Sullivan said his team could begin on-site construction in the same three-month fiscal quarter it gets the requested funding ($6.5 million for Jasper, $9.8 million for Hart). “We’ve emphasized to EPA headquarters that we think these sites are a priority,” Sullivan said. Now all he can do is wait. While the Jasper sites were passed over in the main funding process, Sullivan hopes EPA headquarters can scrounge money for the Jasper sites from the budget’s fringes by redirecting unused funds from other regional offices and other projects, although many of them likely face similar cash shortages. Work on the sites could be delayed as long as two years, he estimates.

EPA Region 6 spokesman Dave Bary insists Superfund isn’t short on money. He points out that while the trust fund is shrinking, Superfund’s overall budget remains the same, about $1.3 billion per year. The difference, says Ed Hopkins in the Sierra Club’s Washington office, is that without the industry tax, the public is stuck with the bill for corporate pollution. In 1995, taxpayers laid out about 18 percent of Superfund’s budget. By 2003 they will pay 54 percent, according to the Sierra Club. Now that the trust fund is nearly gone, the Superfund cleanups must claw for funding in the White House budget along with numerous other federal programs. The resulting cutbacks are evident in the EPA inspector general’s report in which regional offices requested $450 million for remedial cleanups in fiscal year 2002, but received just $228 million. Meanwhile, work has slowed everywhere. EPA finished construction on 47 sites in 2001, far short of its projected 75 completions, and down from 87 the year before. More than 1,500 Superfund projects remain unfinished, roughly 30 percent of them orphan sites.

“The EPA may be able to cover this up by shifting funds, but it can’t do that for very long,” Hopkins believes. He and other environmentalists demand a return of the industry tax, though President Bush and many congressional conservatives oppose such a move. Hopkins argues that public funding of cleanups violates the original “polluter pays” philosophy of Superfund, and notes that every president, including Ronald Reagan, supported the tax on industry. He predicts voters and politicians will become outraged at the Bush Administration’s downsizing of Superfund.

In Jasper, though, there is no outrage, even as remediation work stalls. In fact, unlike at other Superfund sites, no community group or public entity in Jasper lobbies EPA over the Hart and Jasper sites. Laura Banda lives in a blue trailer home with her husband and year-old baby just across unpaved Otis Street on the edge of the Jasper Creosoting Company plot. They’ve been here nine years, but, Banda says, she knows little about the Superfund site just yards uphill from her front door. “Why,” she asks a reporter suspiciously, “is there something I should know?”

Dave Mann is a writer in Austin.