Afterword

The Man Who Shaved Off the Beard of Poetry

“Tell me not in mournful numbers

‘Life is but an empty dream!’…”

So Henry Wadsworth Longfellow began his anthem to the superego, “A Psalm of Life.” My fourth grade classmates and I–perhaps you, too–were forced to memorize all nine stanzas. We had no idea what it meant, of course, only that it was “stirring.” No one would have thought back then to translate Longfellow’s opening lines into 1960s English. Or did nobody dare? Shave the nineteenth-century beard off and Longfellow is pleading: “Don’t bum me out with another awful poem.”

Our textbooks were full of “mournful numbers”–dirges by Tennyson, Wordsworth’s sighs, and, completely incomprehensible, “The Raven” by Edgar Allen Poe–but hard as they tried to make poetry remote, they couldn’t ruin it for me. Mother Goose and Chuck Berry’s “brown-eyed handsome man” glowed in my mouth. Truthfully, I loved Longfellow too, all those rhythms to beat your breast by. Soon, I was writing poems of my own about–what else?–falling leaves.

Several years later and it was the spring of 1968. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed and 300 civilians were murdered by U.S. soldiers in My Lai. A bloodhound-faced LBJ withdrew from the presidential campaign and Bobby Kennedy bled to death on a kitchen floor in Los Angeles. What more could happen? I was 15. Maybe life was an empty dream after all. That same spring we read that student protesters had shut down Columbia University. What we didn’t know was that one Columbia professor had headed downtown and, with schoolchildren, was fomenting an exuberant revolution.

The man was poet Kenneth Koch, a toothy, curly headed man-boy born in Cincinnati. He died of leukemia in New York City on July 6, at age 77. The New York Times and London’s Independent remembered Koch for his role in the so-called New York School of Poets, a band of writers drawn together in the 1950s by their campy wit and infatuation with big city life. But the newspapers missed Koch’s most obvious achievement: inciting a zillion amateurs to take up their pens.

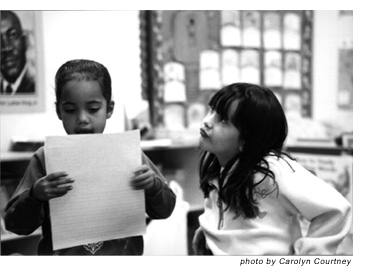

Koch’s uprising began that spring of 1968 at P.S. 61, an elementary school in lower Manhattan, and would change the teaching of poetry and writing. He believed that children–even very little ones–could write their own good poems, and after a few weeks at P.S. 61 he had proven it. With simple prompts Koch called “poetry ideas,” chased by his ebullient confidence, he coaxed children to make poems like this one.

When I lived in Texas I wanted to be big now I live in New York I want to be a baby. When I was in second grade I used to think school was fun but now I am in third grade I think school is a bore. I used to be a pig but now I am a hog. Yesterday I was looking for my banana coat now I am looking for my dress of apples.

This poem by third grader Eliza Bailey was published in 1970 with many others in Koch’s first anthology of student writing, Wishes, Lies and Dreams. Unlike my falling leaf poems, which had sacrificed everything on the dinky altar of rhyme, Eliza’s poem was wild and real. With Koch’s encouragement, she had tapped her own life, her fantasies and humor, sloshing those juices together in a daring work.

“This was all somewhat like a dream coming true,” Koch remembered 30 years later, in his afterword for the new edition of Wishes, Lies and Dreams. “Once I saw that children could be made excited about writing poems, my task was to find ways to keep them so while making what they wrote more and more of the true nature of poetry, a medium in which you can say extraordinary things and have them given a kind of truth by music.”

Colleen Fairbanks, associate professor in the University of Texas’s College of Education, says that Koch’s books on teaching poetry writing, “came out at the beginning of the whole writing process movement, and at a time when poetry was treated as some sort of rarefied air that only the select could breathe. He was the first person that I ever heard of who really suggested that kids not only could but should write poetry and provided teachers with some way of doing that.”

Most of my early teachers had steered gently away from poetry writing, focusing on terminology instead: alliteration, simile–the kind of stuff that “could wind up on the quiz.” As a visiting poet, Koch wasn’t going to give grades. He just invited students to notice and play with the musical dimension of language, not caring whether they could name the techniques they already had begun to use. His method, explained in all his books on teaching, is fairly simple: Read a delicious example of some “poetry idea” or invent new examples on the spot, pass out pencils and paper, let people go, then read all the new poems aloud and praise the best of everything. “I used to be a pig but now I am a hog”: metrically, that’s as solid as anything Longfellow ever wrote, but Eliza Bailey wasn’t toiling after a line of iambic hexameter to get there. Had she ever heard of “surrealism” or “metaphor”? Probably not, but here is a “banana coat” anyway.

Koch’s successes at P.S. 61 and the publicity for Wishes, Lies and Dreams happened at the perfect time. Bizarre as this may sound, Americans in the late 1960s and 1970s wanted local art and better public education more than an Office of Homeland Security or a beefier SEC. Then, arts councils were forming in every state, and the still-young National Endowment for the Arts, later to become such a theatre of pieties, was expanding fast with public support.

Koch’s first teaching experiments in 1968, in fact, were paid for by the National Endowment for the Arts, and the very next year, the NEA began a program called Artists-in-Schools with $100,000, putting visual artists into six school districts around the country. The program took off. By 1973, poets, actors, musicians, artists, and dancers were working in classrooms in all 50 states, and by 1979 the federal government was paying out $4.86 million–matched by state and school district money–for artists to teach.

By the time Kenneth Koch’s approach caught on, I was long past elementary school, but I benefited from his revolution too. In 1980, I began several years of work for the Kentucky Arts Council, the first and last time I’ll ever be paid as a poet. Like the post office murals of the 1930s and the documentary photographs taken then for the Farm Security Administration, Artists-in-Schools convinced the public that art, a special kind of activity, was part of everyday life, too. It’s been one of very few federal arts programs to pay individual artists for their work and the only one to reach places like Marrowbone, Kentucky.

With Koch’s books in hand, I worked in some 20 Kentucky school districts and incited thousands of poems.

Right now my aunt is cleaning hotel rooms in Ohio at Lenox Inn.

My grandma is working in Ohio at the factory making little bears. My Uncle Don is watching ball games.

Uncle Gene is in West Virginia in surgery having a tumor taken out of his neck.

– Angela N., Mt. Sterling Elementary School

A second grader, Angela wrote her poem after a suggestion I took from Koch’s second anthology, Rose, Where Did You Get That Red?, a book that ignores the old “kiddie canon”–no more ravens and daffodils–and assumes that children, like adults, will prefer great poems to mediocre ones. In this collection Koch’s poetry ideas come from works by Shakespeare, Blake, John Donne, Emily Dickinson, the best writers anyone knows. For Angela’s class I had read passages from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” each line describing what someone was doing at that very moment somewhere in America. Then I asked the students to look at the clock, think, and make their own poems, showing with each line what a particular person was doing right then: 9:43 a.m., November 8, 1989. A little stiff holding the pencil but with a surgeon’s steady eye, Angela wrote this hyper-realist poem.

My elementary school poetry studies had been limited to dead Anglo-American and English poets, all those men drowning in their beards, but Kenneth Koch changed that too. He showed children Navajo songs, poems of the Dinka tribe, works by Léopold Senghor of Senegal, Mayakowsky, Gertrude Stein, and Po Chu-i. And of course, his books were packed with poetry ideas from contemporary writers, Imamu Amiri Baraka’s “Poem for Black Hearts” and Gary Snyder’s “Why Log Truck Drivers Rise Earlier Than Students of Zen.” The message was always, yes, poetry is marvelous, but not too marvelous to read and try yourself.

Unfortunately, since the late 1980s NEA, the Texas Commission on the Arts, and other state arts councils, too, have pulled back from artists’ residencies in schools. Ricardo Hernandez, executive director of TCA, writes that “one of the key elements in the residencies at the time that Kenneth wrote his book was ‘flexibility.’ Today’s school day/year does not allow for that in the same kind of way.” Hernandez reports that artist residencies make up only a tenth of TCA’s current arts education budget, but not even the formidable TAAS test can undo Koch’s revolution. At one time, it took a “poet” to get students writing. Teachers, the good ones, know how to do that now.

Along with his teaching guides, Kenneth Koch produced books of fiction, plays, and essays, and 15 collections of his own poetry. Future generations will decide whether his poems belong alongside Whitman’s and John Donne’s. Already, his “poetry ideas” have launched a thousand odes, ten thousand more sailing after them–Eliza’s “dress of apples” and Angela’s clean motel room. The best part of Koch’s legacy is being written in a classroom right now.

Julie Ardery lives and writes poems in Austin.