Highway Robbery: After Wage Theft Complaints, Contractor Still Wins State Business

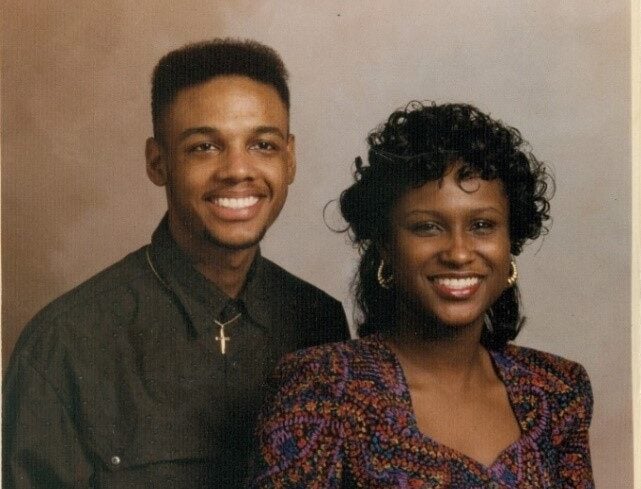

Fort Worth’s Liberty Proclaimed Ministry is a small, family-run company that does a lot of business with the state. Founded by Donna Griffin and her husband, Robert, in 1998, LPM offers Bible study, mentorship and job training for ex-offenders and people with disabilities. The company is also a major subcontractor under a state jobs initiative for disabled Texans. According to Texas Department of Transportation records, LPM holds nearly $2.5 million worth of contracts to clean up the highways around Fort Worth.

Picking up roadside Whataburger wrappers and mopping rest stop bathroom floors may not be the most glamorous job training out there, but if you’ve got a conviction on your record or a severe disability, getting back to work can be a huge step. At the very least it pays the bills, right?

Well, not if you’re working 15-hour days and only getting paid for six. Not if you work more than 40 hours a week and are never paid overtime. Not if you work weekend shifts without getting paid at all. According to Gloria Conley, Michael Jones, Roderick Mukes and dozens of former LPM employees who joined a federal lawsuit last year, that was how LPM and an associated firm called Ministry of Property routinely treated their employees.

According to Michael O’Keefe Cowles, an attorney with the nonprofit Equal Justice Center who represented LPM workers in the lawsuit, employees were expected to work from 6 a.m. till sundown but were regularly paid — at minimum wage — for only six or seven hours.

LPM’s website is full of success stories from folks who credit the program for turning their lives around. But Cowles said his clients wouldn’t be so generous. “It wouldn’t be a stretch to call this the opposite of charity, when you’re stealing from people of meager means,” he said.

One of those clients, Anthony Lacy, worked for LPM from 2010 to 2013. Lacy told the Observer that he’d been out of prison for about a year, after serving time for a drug conviction, when he walked into LPM’s warehouse asking about a job. He left his phone number and got a call back a couple days later, he said, for a position picking up trash along the highway.

LPM describes itself as an intervention in its employees’ lives, with character-building and job-skills programs to prepare workers for better careers. But Lacy said that in his case, there was never a discussion about a choice of jobs or training programs. “The only training is they have someone who walks with you and show you what you’re gonna pick up,” he said. “They make it look good, but once you get there it’s a whole different ballgame.”

Lacy said that childhood hip surgery left him with one leg shorter than the other. His disability hasn’t gotten in his way in previous jobs, even driving a forklift, but it was enough to qualify him for work with LPM.

Lacy was a “walker” for six months before being promoted to a lead on the pick-up crew. As a walker, he said he worked 50 or 60 hours a week but consistently got paid for 33.

“We complained about it,” Lacy said, “but they said, ‘If you don’t like what we’re doing, just go find you another job.’”

According to court records, the case closed last year with two separate settlements: a $200,000 settlement paid by the Griffins and LPM, and a $1 million default judgment against their former associate Herbert Davis, who ran Ministry of Prophecy.

Donna Griffin told the Observer that the complaint against LPM was “all a lie.” She declined to speak about details of the case, but did say there was no six- or seven-hour daily limit to what workers were paid for.

“When you deal with the kind of people we deal with,” she said, “you’re gonna get accused of things. That’s just kind of the way it is.”

Griffin stressed that LPM’s ministry work is focused on helping people whose disabilities and criminal backgrounds have hurt their families and left them without ways to support themselves. She said LPM’s state contracts are what make that help possible. “You can minister to a person,” she said, “but if they still can’t feed their family, how far is the ministry gonna go?”

“I guess you can pull some negatives out of anything,” Griffin said, “because we’re human and we’re not gonna always do it perfectly. But we do more good than we do wrong.”

Wage theft is particularly prevalent in construction, custodial work and other low-paying industries. Its victims tend to be undocumented people, women and people of color. Some cities — Houston and El Paso among them — have responded recently by disqualifying companies with a history of wage theft violations from getting city contracts.

Neither Fort Worth nor the state of Texas has passed wage theft laws, so the only recourse left for LPM’s workers was either a civil case or a complaint to the U.S. Department of Labor. According to federal records, the Department of Labor found three wage violations at LPM in 2009, four years before LPM workers brought their case to Cowles.

In the first investigation, covering a span from 2007 to 2009, investigators found evidence that LPM had withheld around $1,700 in wages. According to Labor Department records, investigators presented their evidence to Donna Griffin in a meeting, and Griffin simply refused to pay. Records from a second investigation show that LPM eventually paid all but $82 of what it owed from the first case. But the second case was closed in 2013 before investigators could confirm new allegations of wage theft.

LPM’s contracts with the state are part of a program providing jobs for disabled Texans. Called the State Use Program, it had been managed by a small state agency until earlier this year, when the Legislature placed it under the Texas Workforce Commission instead. The operation of the program has long been outsourced to a third-party nonprofit called TIBH Industries — that arrangement is still in place.

TIBH Director of Administration Marie Richter told the Observer that she wasn’t aware of the lawsuit or Labor Department complaints against LPM. “This is probably the first time,” she said, that she’d heard such allegations against a contractor. “We don’t really run into this kind of problem.”

A search of a Department of Labor database reveals that 27 of the 114 contractors in the State Use Program have been subjects of wage theft investigations.

It’s been a year since the lawsuit against LPM closed, and Cowles told the Observer that if repeated DOL investigations into LPM haven’t prompted change, the courts don’t seem to be a sufficient deterrent, either.

“After we stopped litigating this case,” Cowles said, “we got calls saying that people were not being paid properly. Still. And that’s the real travesty about this: We litigate these cases to have broader impact, and when those violations continue, that’s a real failing of the system.”