Undercovered

I recently celebrated the one-year anniversary of my “gay” marriage. This is a little odd for me, not because gay marriage is so hotly contested, but because I am not gay. After two divorces, I am even less marriage-interested than I am gay. A lack of health insurance prompted this shotgunish union last summer as my boyfriend Warren and I entered into a domestic partnership—a legal commitment commonly used by gay couples denied the right to a full-on, all-the-trimmings, official marriage.

At the time, I was in chronic, excruciating pain, each monthly cycle triggering an avalanche of agony courtesy of a uterus full of fibroids. The crippling effect grew exponentially to the point that I was regularly bedridden for days on end, gobbling a collection of painkillers cobbled together from my own stash of squirreled-away Vicodin left over from dental work and whatever I might wheedle out of friends who had insurance that allowed them doctors’ visits to replenish as needed.

I had no such luck, opportunity, or whatever you want to call it. Being uninsured, I could not afford to see a specialist. My boyfriend had done what he could to cheer me up while offering at-home remedies. One night, as I lay curled around the toilet waiting to vomit from the pain, he stood behind me singing a Phil Collins song, which, he explained, should hasten my hurling. When I scraped together money to talk to a surgeon who concurred that a hysterectomy would solve my problem, Warren, knowing I did not have $20,000, suggested maybe he could use the bumper of his pickup truck and a bungee cord to remove my lady parts.

I had no such luck, opportunity, or whatever you want to call it. Being uninsured, I could not afford to see a specialist. My boyfriend had done what he could to cheer me up while offering at-home remedies. One night, as I lay curled around the toilet waiting to vomit from the pain, he stood behind me singing a Phil Collins song, which, he explained, should hasten my hurling. When I scraped together money to talk to a surgeon who concurred that a hysterectomy would solve my problem, Warren, knowing I did not have $20,000, suggested maybe he could use the bumper of his pickup truck and a bungee cord to remove my lady parts.

I smiled but demurred and wondered if it would be too much to ask my friends to throw yet another benefit for me. In 2005, when I was walking with a cane, every step as if upon broken glass, and of course uninsured, a nice friend-of-a-friend podiatrist in Chicago offered to fix my structurally deficient, rapidly deteriorating foot for free. I did need to pony up funds to cover transportation to-and-fro the Windy City, lodging while I recovered, and cash to cover the cost of the surgical suite and assistants. Even with the doctor’s services donated, and even after choosing local anesthesia to save money (I could hear the saw as he worked on me), I still was looking at a pretty steep figure. So a bunch of friends and local musicians had an aptly titled Foot-the-Bill party and raised enough to cover it.

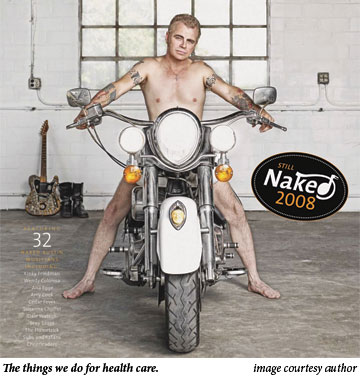

Inspired by this kindness, I went on to similar good deeds. For three years I produced a calendar featuring well-known local musicians naked. The proceeds went to assist uninsured children. I hated that any children were uninsured. But I loved being able to help. (And really, who can complain about “having” to call sexy musicians once a year and ask them to strip?)

While it is so good to live in a city that strives to take care of its own—let’s face it, you can’t swing a sick cat in Austin without hitting a poster announcing a benefit to help a sick cat—I confess there have been many times when I’ve fantasized about having insurance. From time to time, I’ve lived this fantasy, but never for long or without one big catch or another. When my son was little, for example, he qualified for the Children’s Health Insurance Program. That allowed him the checkups required to play sports and, if we needed it, access to emergency care. It also landed us in a CHIP-taking pediatrician’s office, where I—a single mom and nonbeliever—was pressed with literature informing me that I must preach to my son the importance of marriage and religion.

During my first marriage, I had insurance through my then-spouse. As we were divorcing, a swiftly growing, malignant ovarian tumor made its presence known. Insurance covered the surgery that saved my life. After the divorce, now with a pre-existing condition, I did not qualify for my own policy. So I could choose COBRA—the federal program that lets you keep paying for an employer policy for a while after you’d otherwise lose it—or nothing.

Correction: I could’ve gotten a policy, but not one that covered the pre-existing condition. This strikes me as rather like going to a restaurant when you are very, very hungry. Despite the fact that the place advertises itself as a purveyor of food, your waiter informs you that he will bring you a fire hose, or a DVD player, or a pair of boots, but he is unable to bring you physical nourishment. I mean, what is the point of having insurance that won’t cover the thing you need it for?

So I went for COBRA. I was already poor, raising the kid on a freelancer’s unsteady income, with no child support. I’d maxed out my credit cards and was fielding (or rather dodging) daily calls from creditors. I could not pay both the $500 monthly COBRA payment and minimum payments on my cards. I chose the former so I could have my reproductive system monitored every few weeks. Selfishly, I cared more about staying alive to raise my child than I did paying back credit-card companies that were punishing me brutally with late payment fees.

This in turn triggered a bankruptcy. And you know what? I didn’t care about the damage this did to my credit. I was beyond delighted that I’d lived long enough to be declared out of the woods and that I had the (albeit expensive) coverage for frequent checkups.

After the COBRA ran out, I either lived uninsured or on the occasional policy with a catastrophic deductible, which I determined by trying to guess how many friends could loan me how much money in a pinch. Fifty friends with $100 to spare in an emergency, for instance, equaled a $5,000 deductible.

Then came the critical mass—literally—of my fibroids. Besides being so sick, I was pissed off. Even if I could have paid piles of money for insurance, I still had a pre-existing condition. Cash-to-haul-away my parts seemed the only option. Unless I got married and went on Warren’s insurance. We hadn’t been dating a year, and I’d already had those two other hasty marriages. The bumper-and-bungee option sounded more appealing than a return to matrimony.

Then we found out about domestic partnerships. Warren’s company is among those that honor DPs as spouses and cover them. While my fury grew on behalf of all the sick and Warren-less out there—what about people who have no one to gay-marry or regular-marry for insurance? Why are work and marriage even connected to health insurance?—at least I had what I needed.

My surgery wound up running me about a $1,000 co-pay. I am about 60,000-percent better now than I was a year ago. But Warren is leaving his job in a month. Unless and until some reform allows me to buy my own insurance—by which I mean real, true insurance that covers what I need covered—I am back to the place where my next medical crisis will mean: a) yet another benefit; b) reconsidering the pickup-and-bungee combo; c) sucking it up and living in pain; or d) begging someone to take me out back and shoot me.

Spike Gillespie is a writer and controversy artist who lives in Austin and blogs at spikeg.com.