Ted Cruz, Manchurian Candidate

How the junior senator from Texas helped precipitate a milestone in the growth of the Chinese state.

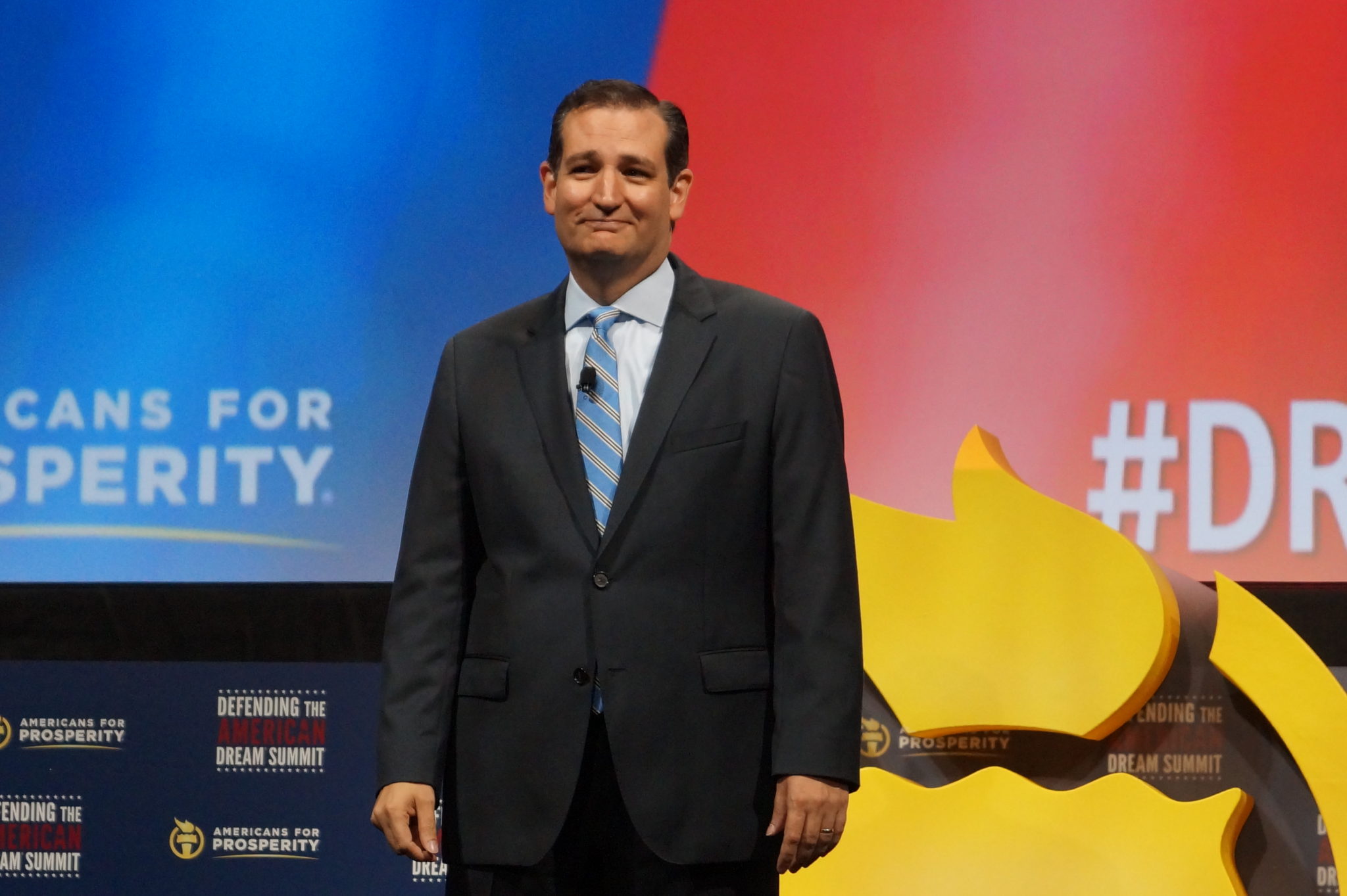

Above: Ted Cruz receives rapturous applause at a conference put on by Americans For Prosperity in Dallas, August 2014.

Yes, Ted Cruz hails from a foreign land, as late-night comedians and the nation’s hackiest political commentators have been happy to inform you. But the headline is about something else. Something that you wouldn’t normally read about in the Observer: The games great powers play in Asia. In March, we’ve seen some important milestones in the gradual expansion of Chinese state power—events that our state’s junior senator had a small but significant role in bringing about.

If that sounds like a stretch, let’s go back a bit. Over the last few weeks, we’ve witnessed the growth of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, an international financial institution first proposed by the Chinese government in late 2013 that really got going in the second half of last year. The AIIB is intended to be China’s answer to other financial institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Asian Development Bank, banks in which the United States, Europe and Japan have outsized influence.

The AIIB’s stated goal is to raise and distribute capital for the development of major infrastructure projects in Asia, for countries that can’t afford them on their own. Whatever you think of financial institutions like the IMF and ADB—they have plenty of detractors—the creation of a rival institution through which China can build influence in Asia is clearly suboptimal from the perspective of American power.

The primary reason China wanted the AIIB in the first place is that it has been getting cut out of the decision-making process at the international banks—it was growing wary of the ADB, in which its rival Japan is the biggest stakeholder. And despite putting more and more money into the World Bank and IMF, it didn’t have voting power in the organizations commensurate with its new financial power. This seriously irked China, and there’s good reason to believe that talk of the AIIB might have begun as nothing more than a threat intended to force change.

In all things, Cruz and his friends don’t want the branches of American power to bend.

Congress being Congress, it went for years without doing so. But then, last spring, it finally looked as if it might act. Senate leadership attached the badly overdue IMF reforms to an aid package to the faltering Ukrainian government, which would be getting assistance through the bank. Cruz played a critical role in killing it. Here’s what the Observer wrote in April about how things went down:

Cruz released an open letter to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid announcing his intention “to object to any floor consideration of Ukraine aid legislation that contains these IMF provisions.” It’s been reported that Cruz asked all Senate Republicans to co-sign the letter. In the end, only five did (stalwart Cruz ally Mike Lee and the idiosyncratic Rand Paul among them.) The letter is full of blank lines for signatures that were not provided. Nevertheless, the bill started to have problems.

House Republicans began announcing their intent to oppose the Senate language. A growing number of GOP Senators began to express disquiet. That left longtime Cruz nemesis John McCain sputtering with fury. Those who were hoping to slow or strip the bill were “on a fool’s errand,” just like the government shutdown. They had left him “embarrassed” by his party.

But the opposition to the bill grew. The aid bill slipped into the next week—then the next. What had begun as an uncontroversial provision had become a poison pill. Marco Rubio joined the crusade, though he didn’t go as far as Cruz. (He’d previously characterized the reforms as “Russian-backed.”) It became apparent that many were willing to kill the Ukraine aid bill rather than accept the IMF reforms. Early last week, Reid conceded defeat—he’d strip the bill.

It was the closest Congress had come to ratifying the IMF reform package, and its failure left congressional Republicans more unified in opposition to the reform measures. The fiasco seemed, to many observers, evidence that Congress would never let China and other emerging economies have more voting power.

And so the Chinese search for an alternative accelerated. A few months later, it unveiled grand plans for its new bank, and observers told the Financial Times the proposal was directly tied to the death of IMF reform:

“China feels it can’t get anything done in the World Bank or the IMF so it wants to set up its own World Bank that it can control itself,” said one person directly involved in discussions to establish the AIIB.

Now, Cruz’s quixotic killing of IMF reform wasn’t the only time Uncle Sam shot itself in the foot over the AIIB: As Dan Drezner writes in the Washington Post, the Obama administration’s hopeless bungling of the issue now means U.S. allies are becoming founding members of the bank against American wishes, while the U.S. is out in the cold—where the smart thing to do might just have been to join the bank, too.

But Congress—and Cruz specifically—bears a significant amount of blame. Plenty of Republicans were happy to vote for IMF reform until it was made a litmus-test issue. Some Republicans now acknowledge stalling on the IMF package was a mistake: Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, no hippie squish, told a policy forum in Brussels recently that the policy fumble was “an unfortunate event and it might be bigger than we understand today.”

Would the Chinese have launched the bank anyway if IMF reforms had been passed? Maybe so—but that’s a question historians might debate someday as they chart the rise of Chinese influence in Asia.

It’s a crummy way to manage a superpower whose influence is in relative, though not absolute, decline. It’s one of the few things Cruz has done in Congress that has had real consequences. Now, of course, he’s asking for control of American foreign policy.

In all things, Cruz and his friends don’t want the branches of American power to bend. They use words like “muscular” to define their approach to the world: They see compromise as a sin. Branches that don’t bend break, of course. But there’s a danger, too, that our friends will just go find another tree.