Senate Committee Considers Ways to Nurture Online Education

From full-time virtual schools to a la carte online courses, lawmakers trust in online education's potential, despite questions about performance and student turnover.

The Texas Senate’s education committee continued its off-season studies Monday morning, taking a long look at the future of public schools—or at least, one notion of what that future looks like. The interim charge handed down by Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst was to “study the growing demand for virtual schools in Texas. Review the benefits of virtual schools, related successes in other states, and needed changes to remove barriers to virtual schools.”

To paraphrase: “Hey, virtual schools. You’re pretty great. How come you’re so great?”

There are some who’d take issue with the premise—noting virtual schools’ poor performance in Texas, their growth despite that poor performance, and the profit motive driving the virtual school market.

While the Education Committee just got itself a new chairman last week—one whose enthusiasm for school choice most definitely extends to full-time online schools—the job of running yesterday’s meeting fell to Democratic state Sen. Leticia Van de Putte.

Texas students have two options for taking online courses today, both under the umbrella of the Texas Virtual School Network. First, there’s a network of online courses available to any student in Texas’ traditional public schools, for rural students without access to specialized classes or dual credit from a university. Second, Texas has three full-time virtual options for students (in grades three to 11 this year) who don’t want to attend a traditional public school. All three are run by national online school corporations, two of them for-profit.

Those full-time virtual schools get most of the attention—most recently in a report from the education advocacy group Raise Your Hand Texas released last week, which found that enrollment in Texas’ full-time virtual public schools has grown from 171 students in the 2006-07 school year to 6,209 students last year. The report also noted a huge demographic difference between virtual and traditional public schools; in 2011, 59 percent of Texas’ public school enrollment was economically disadvantaged, compared to 8.5 percent of virtual school students. In virtual schools, a much higher share of the students were white, and far fewer were Hispanic.

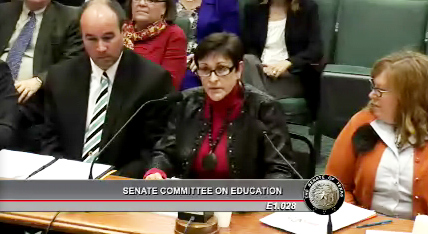

On Monday at the Capitol, Houston ISD’s charter school compliance officer Nancy Manley (pictured at right) described the growth at Texas Connections Academy, which she launched back in 2008 with 50 students. Enrollment has grown to 2,740 this year, she said. (Connections is a for-profit virtual school operator that Pearson acquired in 2011.) Under Houston ISD’s system of rewarding teachers for student test scores, Texas Connections Academy teachers earned $75,000 for the 2010-11 school year, Manley said.

On Monday at the Capitol, Houston ISD’s charter school compliance officer Nancy Manley (pictured at right) described the growth at Texas Connections Academy, which she launched back in 2008 with 50 students. Enrollment has grown to 2,740 this year, she said. (Connections is a for-profit virtual school operator that Pearson acquired in 2011.) Under Houston ISD’s system of rewarding teachers for student test scores, Texas Connections Academy teachers earned $75,000 for the 2010-11 school year, Manley said.

Connections’ dropout rate for 7th and 8th graders in 2009-10 was 5.4 percent, which Manley conceded was “outrageously high,” one major factor behind the school’s “unacceptable” rating from the state in 2009-10. The next year, Manley said, the dropout rate plummeted to four-tenths of a percent, just a bit higher than the Houston ISD average, three-tenths of a percent. “That was because they just put a system in place to track those students” that left, she said—something the school hadn’t been doing before. Before that, she said, every student that left the school to enroll elsewhere was counted as a dropout.

Leaving aside the data from Texas Connections Academy, others agreed that there’s a great deal of turnover in virtual schools’ enrollment. Some said parents often only plan on enrolling their kids in virtual schools for a year or two. Mary Gifford, senior vice president with K12 Inc., the for-profit giant that runs the Texas Virtual Academy, said the most common reason students leave is because virtual schooling is just so demanding. “There’s a finite universe of kids who can school full-time virtually,” she said. “It is truly a lifestyle choice. The blended model is clearly where the vast majority of students will end up.”

“Blended” learning—using online lessons alongside traditional classroom instruction—was popular among nearly everyone who testified Monday, including teacher groups that oppose school choice or other ideas that could undercut the teacher’s place running a classroom. Sen. Florence Shapiro, the longtime committee chair who is leaving the Senate to work for an online education consultant, said blended learning opens opportunities for teachers to do more with their classroom time, to be a “conductor” instead of just a lecturer—“the musical conductor, not the conductor on a train,” she clarified.

Rural superintendents and wireless access experts described some more basic challenges to opening access to online lessons in towns where there’s no good cell signal or broadband connection—precisely the communities meant to benefit most from virtual learning. Dallas Sen. Royce West said it’s no good to talk about new virtual learning programs when schools don’t have the money to pay for computers, iPads or other equipment students need to take the courses.

“If we’re gonna be talking about blended learning, if we’re gonna be talking about making certain kids use e-books and things of that nature, we’ve got to make certain that they have access to it,” West said. “We cannot make a promise to the kids of the state of Texas that they will have that access, and then not keep that promise.”