Saving the Mint

A version of this story ran in the July 2012 issue.

The first time Priscilla Swafford heard about the community center, she didn’t believe it. She was standing in her apartment. There was a knock on the door. When she opened it, there were two fresh-faced Latinos. They looked like they were in their early 20s. They were holding clipboards.

The first time Priscilla Swafford heard about the community center, she didn’t believe it. She was standing in her apartment. There was a knock on the door. When she opened it, there were two fresh-faced Latinos. They looked like they were in their early 20s. They were holding clipboards.

“Excuse me,” one of them said. “My name’s Frank Garcia. We’re looking to create a community center at the complex. Could you tell us your top three concerns about living here?”

Swafford—everyone in the complex calls her Ms. P—remembers looking at him. “And I said, Lord, you have got to be kidding me.”

To understand her shock, you have to understand something about The Mint apartment complex and about Alief, the Southwest Houston neighborhood where the complex is located. Alief has one of the highest crime rates in Houston. It also has one of the highest populations of former prisoners in the state. About 500 former inmates a year—some originally from the neighborhood, some from elsewhere—move to Alief, according to a study by the national Urban Institute. They arrive—often without jobs, or the skills to find them—to a community with few opportunities.

Many end up at The Mint. Among the few apartment complexes in Alief that admit people with felony records. The Mint is a sort of clearinghouse for people with no place else to go. By the time Ms. P arrived in 2007, The Mint had become one of the most dangerous apartment complexes in Alief, according to Houston police.

Ms. P showed up with the clothes on her back and not much else. She’d just spent four months in the Harris County jail on a drug possession charge. She came out to find that her husband had taken everything—her car, her money—and left town. The Mint was one of the few places that would take her.

“We’d have shootouts in the parking lot,” she said. “I’m talking, grown men firing AK-47s at each other. Abandoned units being used as crackhouses, as whorehouses. Women turning tricks out of apartments. And among it all, we got all these kids running around with no one to watch them.”

Sakina Lanig, field coordinator for state Sen. Rodney Ellis, said she wouldn’t hold events at The Mint without guards. The senator’s district includes Alief.

“It was a place you just didn’t go,” she said. “You didn’t want to be caught there without a really good reason.”

Alief is also racially fragmented. The Mint is predominantly black; Frank is Latino.

Frank recalled his first response to organizing in The Mint: “People were saying, you think you’re going to come into this black neighborhood, you gonna fix things? Boy, you’re gonna get your ass kicked.”

But behind Frank’s idea for a community center was something bigger. He was thinking: save The Mint, and maybe we can save the neighborhood.

Francisco Garcia—or Frank, as he asked to be called—is 24, with a round face and an easy, almost goofy smile. When I met him he was wearing a short-sleeved button-down shirt and khakis.

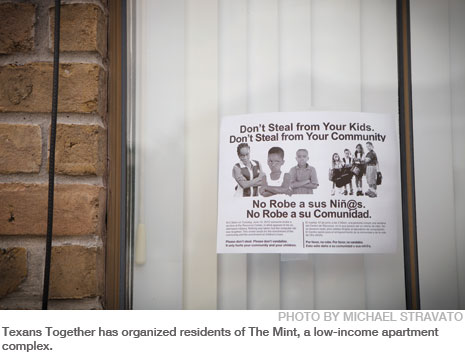

Garcia works with Texans Together, a nonprofit organization that educates people in what it calls “underserved neighborhoods” in the basics of community organizing and activism. They hope that by developing local leaders from within the community, and by getting residents a forum in which to talk to each other, they can reduce crime.

“In a lot of ways Alief is a microcosm of Houston. It’s a very diverse neighborhood. It’s majority-minority. There’s a huge amount of young people. A lot of income inequality. A lot of rental multi-unit housing. And around Houston, all those are growing trends,” said Brendan Laws, a community organizer with Texans Together. “Alief is attractive [to organizers] because it represents the trends in the rest of Houston. But unlike other neighborhoods like it, it’s very underserved. It doesn’t have the nonprofit involvement that other neighborhoods in Houston do.”

The Mint is a sprawling collection of freestanding two-story apartment buildings, all made of brick and brown clapboards. It’s huge, almost a small village, with 500 units housing about 800 residents. Rent ranges from $400 a month for a one bedroom to $700 for a three bedroom. All things considered, it looks pretty nice.

There are parts of Alief where every gate in every apartment complex is broken. During a tour of the neighborhood I saw plenty of boarded-up units; plenty of the boards had been smashed. At one, I saw a unit where the entire roof was gone. People were living next door to it.

I got to The Mint the day after Texans Together broke ground on a new playground, a big concrete square surrounded by construction equipment, and before he would let me interview him, Frank had to show it to me.

“See here,” Frank said, “this is where the swings are going to be. This here’s going to be a jungle gym. And here—” he led me around a corner to a grassy field where the old playground used to be—“we’re putting in a community garden.”

Frank was 19 when he first knocked on Ms. P’s door to ask her about her community concerns. That in and of itself was a bit of a miracle, he told me, because growing up in Alief, he was pretty certain he wouldn’t make it out of high school alive.

His parents—immigrants from Mexico—had moved to Alief right around the time it was transforming from a sleepy rice-farming community into one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Houston. The change happened astonishingly fast. As late as the 1970s, Alief was still rural, a small town tucked outside the city. Back then, as one longtime resident put it, Alief was mostly “rice-fields and bait shops.”

The rice-fields are paved now. In the 1980s, Alief was touted as a bedroom community for the upper middle class. It would be the next Katy, the next Woodlands. Rice field after rice field was bulldozed. Condo complex after condo complex went up.

The hoped-for yuppies didn’t come. Gradually, as apartment managers realized they had overbuilt, prices dropped. New signs went up: First Month Free. Then: First Two Months Free. As the prices dropped, people moved in: poor people from the city and working-class immigrants from a hundred different countries. Alief became one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Houston—a place where driving east to west you pass through a dozen ethnic enclaves, from the Jewish area to the Taiwanese neighborhood, where street signs are in Mandarin.

Alief was affordable for Frank’s parents. His dad was an electrician and maintenance worker. When he had work, the family had a place to stay. When he didn’t, they were often homeless. When Frank was 9, his dad lost his job and the family was kicked out of their apartment. They moved their belongings into a storage unit. They had nowhere else to go, so they slept there, too.

But Alief was cheap enough that they could mostly make ends meet. Growing up in Alief’s apartment complexes, Frank said, he made friends whose parents spoke a dozen different languages. “We were Indians, Taiwanese, Vietnamese, Hispanic, African-American, white kids,” he said. “But we had one thing in common. We were all poor, and we were all hood.”

Alief then was becoming a sort of no-man’s land—a ghetto island sandwiched between the richer neighborhoods of Southwest Houston, like Bellaire, and the suburb of Katy. Frank and his friends had a lot of pride, and they reveled in Alief’s hardscrabble reputation. It made them feel tough, independent. They wore shirts that said “SWAT”: Southwest Alief Texas.

“If I went to a mall just on the boundary of the Northside, and I was wearing my Alief shirt, well, you would know I was out to fight someone. Because someone was bound to call me out, and say ‘Hey, Fuck Southwest. Fuck you, get out our neighborhood.’ Then we were going to fight,” Frank said.

He sighed. “That caused problems when people started getting shot. That started happening around when I hit 5th grade.”

By the time Frank entered middle school, he was already smoking weed, already drinking. He was used to getting shot at. His two older brothers were in gangs—the Latin Kings and Southwest Cholos.

One day, members of a rival gang came to his house looking for his brother. His brother wasn’t in, so they beat up Frank’s mom in front of him.

By the time he was in high school, Frank had become used to constant paranoia—a certainty that, at some point, things were going to go down.

“We thought: we know how we’re going to die, someone is going to kill us,” he said. “And having that thought in your head, we were all in this paranoid state of mind, this real quiet type of paranoia. This stress that never ends.”

He looks back on that now. The stress was justified. A lot of his friends didn’t make it.

When you’re living like that, he told me, you’re living day to day. You don’t care about the future. You don’t care about consequences. Frank and his friends would blow off class at Elsik High School and walk across the street to The Mint. They’d break into vacant apartments, drink, smoke weed, hang out with girls.

When Frank was 17, his girlfriend Gina got pregnant. The two married and moved into an apartment complex in Alief that accepted Section 8 housing vouchers. It was a new property, but it wasn’t super-safe. Frank remembers standing with Gina on their balcony one night, watching a shootout between two teenagers.

“I think when you’re used to living in bullshit all the time, you sort of just give up,” Frank said. “Because you’re so used to living in shit, it’s just normal. You go on autopilot. I wasn’t ready to be a father. I wasn’t ready to have someone in my life. I grew up—we all grew up—being told, hey, you cry, you’re a punk. You show your feelings, you’re a punk. You’re a man, you keep it inside, you don’t ask for help. Until you just explode.”

About a month after his daughter was born, Frank exploded. He doesn’t remember what the fight was about, but he remembers how it ended. He was raging, yelling, punching walls. His wife hid in the bedroom with their daughter. Frank broke the door down. His wife was on the phone to the police. They showed up minutes later.

Frank spent the night in jail, and when he came out his wife and daughter were gone.

“She said, ‘I’m not raising my child around you,’” he said. His eyes were wet when he told me this. “She said, ‘I don’t want to be living with no deadbeat druggie.’”

We were sitting outside The Mint, on a curb under a tree. Frank, who had been talking steadily in the fluid, slightly lilting cadence of the urban street, suddenly stopped. I looked over at him and he was shaking, his hands over his eyes. I didn’t know what to do. I reached over, put my hand on his shoulder. We sat there for a long moment.

Finally he wiped his eyes. “And that, man, that’s when I suddenly realized I wanted to live. That I’d been spending my life breaking the neighborhood down, not building it up. That if I didn’t do something, my daughter was going to go through life just like I did. I didn’t want that.”

He was 18 years old, in an empty apartment, knowing things had to change.

Frank started to come up with a plan. “I just wanted for us youth to be able to come forward, say what life was like for us, and to be able to put forward some solutions, not just complain.”

He and a bunch of friends formed an organization called Unified HOODS—Helping Others Out During Struggle. Twenty to 25 of the members, all of them in their teens, all dressed in saggy shorts, went to a community meeting organized by Houston elected officials.

“We walked into that first meeting, we got some looks,” Frank said. “It was all these old white people—I mean the older generation of Alief, the people here before my parents. We didn’t have anything planned. We just wanted to say, ‘hey, we look like bum-ass street kids. But regardless of how I look, or how I seem, we’re human beings who want to live a good life. Not a rich life, not a wealthy life, but a good life.’

“Just one after another, when the time came for citizen response, we all walked up to the microphone. And we said, this is what it’s like for us, growing up poor in the hood. This is what it’s like, going day to day. This is what it’s like, having gangs running your apartment.

“And we finished and we asked them for help.”

Frank didn’t realize at the time that he was doing community organizing. “[If] you’d have asked me, I wouldn’t have known what that meant.” But he had a natural talent for it, and he was persistent. When the response from city officials and other community members was underwhelming, he kept at it. He kept going to meetings, bringing as many of his friends as he could coax.

Organizers in Alief were looking for someone like Frank—someone young, from the community, who knew the apartment complexes and the people and wanted to help make a change.

“I first met Frank at a community parade,” said Lanig, the field coordinator for Sen. Ellis’ office. “He was walking along, his pants around his ankles, looking like a gang member. And I thought, what’s this kid doing at a parade? And I walked up to him. I said, ‘Unified HOODS,’ that’s an acronym. What’s it stand for? And he said something in what sounded like English. And I said, ‘Boy, we need to talk.’”

The neighborhood was at a crossroads, Lanig said. But no one knew what to do about it.

“Alief’s a place where a lot of people come, fresh out of prison, looking for drugs, looking for trouble, looking for women,” said Lanig. “We figured, if they can’t get money for food legally, they’ll find some way to survive.”

In an attempt to address crime, Alief’s management district—a coalition of local businesses—had established a fund for capital improvement projects, including community initiatives like after-school programs, or GED classes, or community centers.

Frank finally found himself at a town hall meeting organized by Texans Together to discuss these and other projects. After she heard him talk, Maureen Haver, then the organization’s director, offered him a job on the spot.

Frank picked The Mint for his community center project partly because the need was so dire and partly because he used to hang out there. In 2008, with support from Texans Together, he made a deal with The Mint’s property managers: If they would give him two units for a community center, he’d organize the residents to do all the programming. Texans Together would pay for everything else. The goal was to create a self-sustaining community center that could be run by the residents, with minimal support from Texans Together.

So Frank started knocking on doors. He’d ask, what are your top three concerns about living here? At first, as with Ms. P, the response was skeptical.

“We were being doubted a lot because we were Hispanics, coming to a majority African-American community to organize. They’d say, ‘What do you know about my struggle?’ I’d say, ‘I was poor. I know what that’s like. Poor doesn’t have any color.’”

Gradually people started to open up. They had issues with the crime, the violence. They also had more prosaic concerns. They wanted English as a Second Language courses, computer literacy courses, after-school programs.

“Residents would say things like, ‘Man, I want to apply for a job, but I don’t know how to put together a resumé,’” Frank said. “And I’d say, ‘OK, man, we can work with that.’ And I’d sit down with them, spend an hour with templates on Microsoft Word, putting something together. And then they’d go to their friends and say, ‘Hey, those people at the center, they really helped.’ And then suddenly more people want resumés.”

A workforce development service would also come to the complex to help residents.

Texans Together got the Alief school district to donate computers; the public library gave them books. And they had residents start teaching classes. There’s homework help for kids; Boy Scouts; dance classes for girls; lunch programs. Ms. P, who was skeptical about Frank when he first started organizing in The Mint, started teaching a health and healthy relationships class for women.

In 2009, Texans Together turned the center over to the residents. The organization selected a manager from among the residents, and stepped back into a supporting role.

Three years later, the center is still going. And by most measures, it’s been a success. According to Texans Together, some 40 to 50 residents—about 5 percent of the complex’s population—use the center daily. Crime at The Mint had gone down nearly 20 percent, according to police. According to the Alief constable’s office, the Mint has gone from No. 4 on the list of Alief’s most dangerous complexes to No. 29. The murders, the rapes, the drive-bys have become largely a thing of the past.

When I asked Lanig what she thought about the programs at The Mint, she didn’t hesitate. “Imagine a list of the top 10 people who are helping to save Alief,” she said. “Frank Garcia is high, high on that list.”

The community center at The Mint is a pilot program. Frank continues at the center in a support role; Texans Together lets residents use the nonprofit to apply for grants and fundraise. Now Frank is trying to figure out a way to export it to Alief’s other complexes.

That’s not the end to the story, exactly. The Mint’s problems and Alief’s problems are too deeply set to be erased in a few years. The Mint is still a dangerous place. Frank still carries a registered gun out of habit. There is still crime.

And there is tension with the residents. When she didn’t get the job as center manager, Ms. P decided to boycott the center. Frank often finds himself in the uneasy position of mediator between other people’s disputes.

Frank’s life, too, is uneasy. He and his wife got back together. They now have two young children. As many men who have stepped back from the edge do, he credits her with saving him. (“My wife came into my life,” he said, “and all my peers started to disappear. To go into prison or die.”) He has a steady job with Texans Together. But the couple doesn’t make much money, and his family doesn’t have health insurance.

I asked Frank why he is still in Alief. There had to be other places he could live.

He shrugged. “I know, man. There are. But this is home. This is our community. If we don’t fix it, who’s going to?”

Saul Elbein is an Austin-based freelance writer.